Preface

On December 13th 1873, members of several families and individuals left Tysoe on a journey to start a new life in New Zealand. In order to commemorate this event a presentation was delivered in Tysoe Village Hall on December 13th 2023 exactly 150 years to the day later. The text below is a slightly longer, modified, version of that presentation.

Contents

Click on the links below to navigate to different sections:

Introduction

Social and Economic background

Joseph Arch

The Passengers

The Voyage

New beginnings

Further reading

Acknowledgements

Introduction

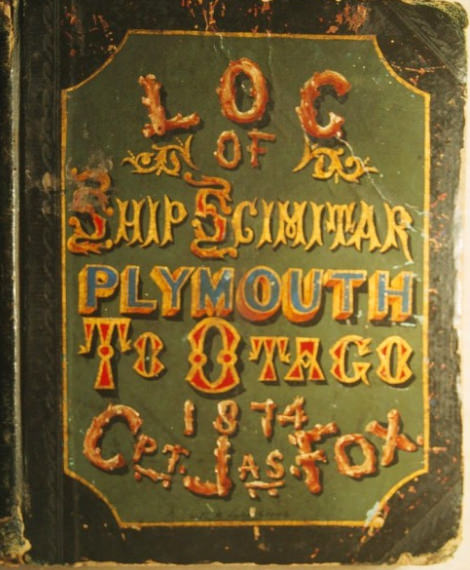

150 years ago, 36 inhabitants of Tysoe, almost all of whom were from long-standing families whose relatives and predecessors can be found immortalized on memorials in the churchyard, left to follow a new life in New Zealand. They emigrated on December 24th, Christmas Eve, 1873 on a ship called the Scimitar which sailed from Plymouth arriving in Otago, New Zealand on March 5th 1874, a 12,000 mile voyage of around 70 days. These emigrants we refer to as The Tysoe 36. Even in the long and eventful history of this village, it seemed appropriate that this momentous event should be commemorated and that the occasion of its 150th anniversary should not slip by unnoticed.

There are three parts to the story: the first is to try and explain the background to life in Tysoe in the 19th century and why people should take such dangerous and extreme measures to leave – an issue of social and economic history. The second part looks at the ship on which they sailed – the Scimitar – and the events that occurred on the voyage, partly through correspondence from the families themselves, but mostly based on the hand-written ship’s log of the Scimitar’s master Captain James Fox which was rescued by his great grandson Michael Beith and published in 2019 in a book entitled No Gravestones in the Ocean. Beith’s emphasis, however, is not so much on the hundreds who emigrated (including The Tysoe 36) but on the fact that the Scimitar was a diseased ship whose very voyage to New Zealand was subsequently the subject of a Public Enquiry. The New Zealand Prime Minister was later to describe the vessel as ‘a floating pest-house’. When The Tysoe 36 eventually arrived in New Zealand, where did they go, what did they do? Did they find a land of opportunity, a land flowing with milk and honey, as had been promised? Their letters home, or at least those to which we have access, constitute the third and final part of the story.

Fig 1. Cover of the Scimitar’s log.

https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~ourstuff/genealogy/Scimitar.htm

Migration and emigration were nothing unusual throughout the 1800s – they both occurred in numerous locations in Britain, the underlying causes usually being economic, social or both. In the case here the need to populate a new part of the Empire coincided with a time of growing poverty and frustration among rural communities in a society that was becoming sharply divided. Those who worked the land were dominated and suppressed by those who occupied or owned it. For many agricultural workers emigration was an option to escape, to pack their bags and leave for Canada, Australia or New Zealand and start a new life. New Zealand had become a British colony in 1841 and the first tentative emigration took place shortly afterwards. It started in comparative dribs and drabs, driven by a short-lived gold rush until the fledgling New Zealand Legislative Assembly finally became effective in the late 1860s. The Assembly recognized that foremost it needed to introduce thousands of new settlers to farm the vast areas of woodland and bush freed up from displaced Maoris. To achieve this, in 1871, it passed the Immigration and Public Works Act. This Act effectively placed all issues of immigration, namely the establishment of offices throughout Europe, the organization of agents, advertising, recruitment and the chartering of ships under the control of the General Government. It was a major political expedient that turned the dribble of colonists of the 1860s into an organised diaspora of tens of thousands from all over Europe. By the end of 1873 scores of ships were already leaving British ports destined for the New World.

The man in charge at the British end of operations was the Agent General, Isaac Featherston, a New Zealand Prime Ministerial appointee, who had offices in London. He was a remarkable man: he had graduated from Edinburgh with a degree in medicine and practiced in Italy before emigrating to New Zealand where he edited a national newspaper before becoming an MP, then a Cabinet Minister. He was famously known for engaging in a duel with pistols in which both parties missed their target. The well-being of the emigrees, including The Tysoe 36, would have been his responsibility from start to finish.

Social and Economic background

Leaving for New Zealand was not just a knee-jerk reaction to a particular event, but the culmination of a series of events that had their roots in a preceding century of growing unrest and dissatisfaction among the labouring classes. Tysoe and other rural parishes still existed in a manner which although not feudal, might as well have been. Socially and administratively the landowners were at the top of the pile, agricultural labourers were at the bottom, and the tenant farmers who paid the labourers lay somewhere in the middle.

Some, but by no means all of the problem can be laid at the door of the inclosure acts, in Tysoe’s case this was in 1798. Before enclosures, the lot of the agricultural labourer was hard but arguably fair. A man could receive his wages from a farmer for work in the fields and supplement it with a few animals fed from common heath. He could heat his home and cook using timber taken from common furze and keep himself and his family in food from tilling a share of common fields. These were not ‘rights’ in any legal sense, although there were many who saw them as such. These were customs the origins of which no-one could remember, other than the fact that it was how life had always been, and it gave their lives a degree of independence. This was the ‘old system’ – a system that became largely wiped away by the inclosures, especially so in the Midlands, where great tracts of common land were redesignated or sold off to larger farms. It made the labourer completely beholden to the benevolence of the tenant farmer who paid him. It was a system that served to emphasise the gulf between social classes; it sharpened the bitterness of those who worked the fields and increased the greed of those who owned or rented the land. The common land that was left for the labourers was, in Tysoe at least, little to write home about. In her book on the life of her father Joseph Ashby, Margaret Ashby recounts the grumblings of an elderly man who remembered the benefits of the old system and the shortcomings of the new:

“They give folks allotments instead of their rights, on a slope so steep that a two-legged animal can’t stand, yet alone dig! In the old days you could walk all through the parish and all round it by the baulks and the headlands and cut wood on the waste if there was any. Do that now and you make the farmer mad”.

These changes generated growing levels of poverty in Tysoe which can be tracked through the Vestry Books. These books recorded the minutes of the Vestry Committee – a committee manned by local worthies. It provided parish administration and met in the church vestry, hence the name. One of its duties was to allocate money to the poor and those without work. The committee was manned by local worthies – namely landowners, employers and those who were required to pay taxes. The Book entries detail, for example, the tonnage of coal required to be discounted to the poor, which poor parishioners should receive support, to whom homeless people could be sent to stay and be fed and/or clothed and which households including children should be given money, how much and for how long. There was even a ‘parish loaf’ specially baked and priced for the poor. The Vestry Committee projected a type of social service, but it had no other option given that the parish was legally obliged to maintain its poor to a certain standard of living. Farmers, on the other hand, were not obliged to pay a living wage and many failed to do so knowing full well that any shortfall could be made up from the parish coffers to elevate a labourer’s wage to that of a pauper. The net effect was that labourers and paupers became much the same.

Insufficient wages among agricultural workers inevitably entailed a degree of poaching of game to keep a family in food; it also entailed illicit removal of wood in order to cook it. Rather than landowners turning a blind eye they appeared to rely more fully on the Game Laws, reflected in an increase in punishments handed out at local level. Some of these were remarkably draconian including young children being thrown into prison or ‘transported’ as it was called to another part of the world for even relatively minor offences. In a nearby parish a 17-year wrote angrily to a judge:

‘If you don’t get rid of your steward, farmer and baliff in less than a month we will burn him up and you along with them. My writing is bad but my firing is good, My Lord.’

As a consequence of this missive he was exiled to Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) for the rest of his life. Furthermore, mechanisation of farming was developing, including the introduction of steam ploughing, which also had an effect on the employment of agricultural workers. Dissatisfaction manifested itself in the burning of hayricks and in the smashing of newly invented farm equipment such as the threshing machine. In Tysoe, papers found stuffed under the floorboards at the Manor referred to a man called Richard Bustin who set fire to a series of hayricks in Brailes in 1834. He was publicly hanged at Warwick. What emerges, as we move through the 19th century, is that those who ran the country, owned the land and paid the wages were adamant in keeping the agricultural class in its place. It was hardly surprising that dissatisfaction turned into riots in parts of southern England and in East Anglia.

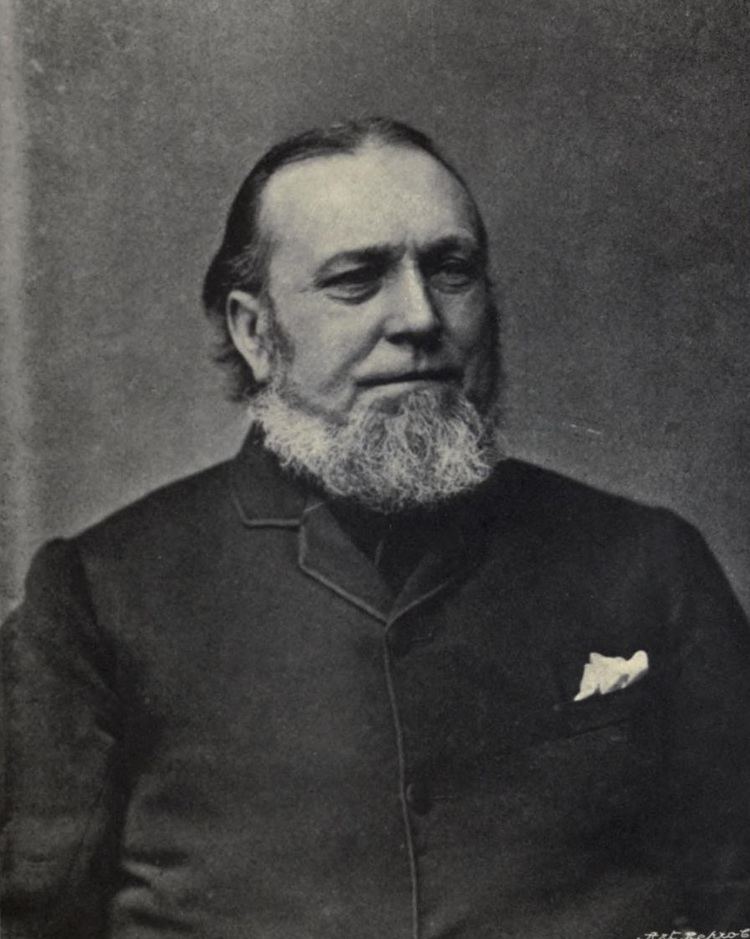

Joseph Arch

This was the social context in which a man called Joseph Arch emerged into the Warwickshire political landscape. He was an unusually well-read and politically astute agricultural labourer from Barford, born in 1826, almost entirely self-taught, and who grew up detesting the inequality of the society he was born into. His autobiography charts his lifelong objections to the way by which land owners and rulers were able to maintain their wealth and position and went out of their way to deliberately keep down the agricultural class in order to preserve the status quo. ‘Workers’, he wrote ‘were no better than toads under a harrow’. Joseph Arch’s dislike of both Parsons and Squires, and their spouses, is well-known. He was a natural speaker – an ability honed by being a Methodist Lay Preacher. He generated an enormous following which provided unprecedented and effective action among agricultural labourers and did much to elevate the image of Liberalism, later becoming an MP himself. His grace, spoken before dinner, became well known:

“O Heavenly Father, bless us, and keep us all alive:

There are ten of us for dinner, and food for only five”.

Fig 2. Joseph Arch.

Image from ‘Notables of Britain: an Album’ by Elliott and Fry.

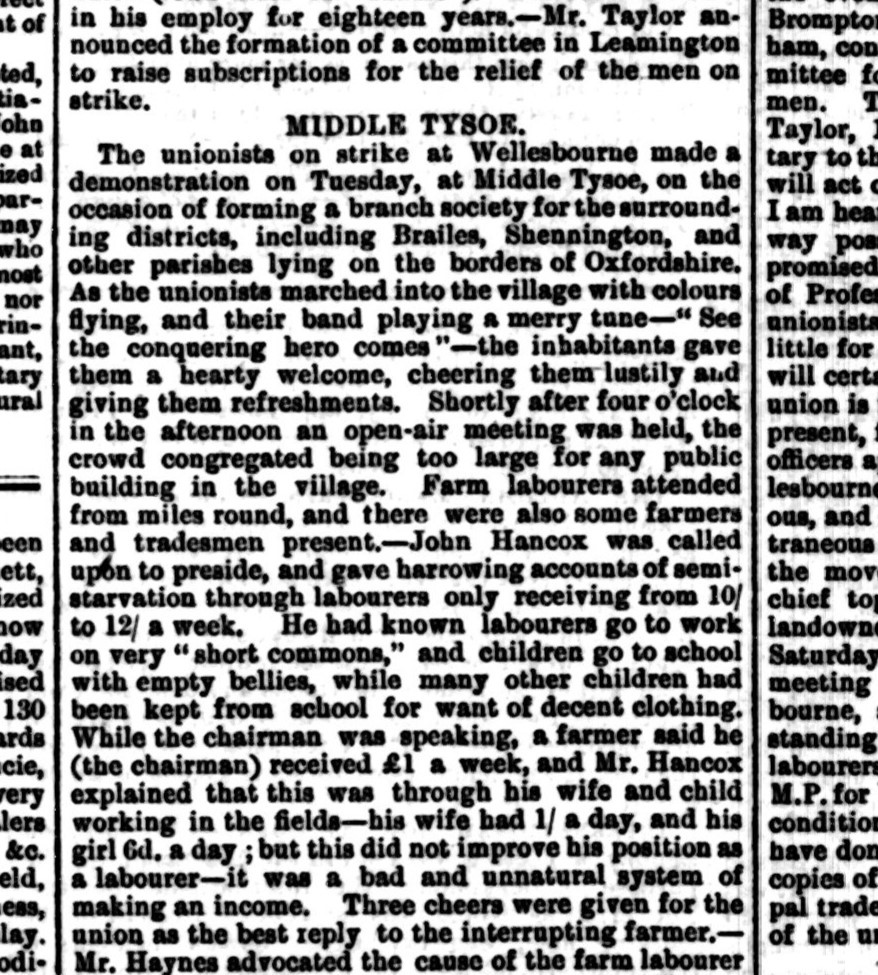

A turning point came in February 1872 and was the inspiration for the founding of the National Agricultural Labourers Union when he was invited to address fellow labourers in Wellesbourne on the injustices of the agricultural system. It was by the tree at the Stag’s Head and turned into a rally. Hundreds of labourers walked there from villages in the vicinity, and social order was turned upside down. The following month Arch came to speak in Tysoe in front of crowds from Oxhill, Whatcote, Brailes and Shenington, arriving with a brass band in full flow. He spoke about wages, housing, underfed children and a world in which folk would no longer be trodden down and kept in their perceived place. It was powerful political stuff which had squires and parsons on the back foot. He was undoubtedly one of the ‘local agitators’ criticized in the Tysoe Magazine in early 1873 by the Vicar of Tysoe, the Rev. C. D. Francis for destroying the bonds between labourer and employer and between clergy and flock. Francis also argued that the increased average wage to around 12 shillings a week was in danger of introducing an unnecessary degree of ‘worldliness’ into a man’s life. At the close of Arch’s meeting, men flocked to join the union. One of the people listening was a young lad of 13. His name was Joseph Ashby who, like many others who had heard Arch, rushed home flushed with new ideas.

Fig 3. Wiltshire & Gloucestershire Standard March 30th 1872.

In short, by 1875 the new Union had almost 60,000 members in some 1368 branches across the country. During that growth Joseph Arch’s aim of fairer pay and conditions were brought to public attention through the emergence of both local and national press. Strikes by Union members had a major and unprecedented impact but was countered by farmers many of whom refused to pay Union rates or employ Union members in what became known as a lock-out. This was a far cry from the idyllic picture of the happy and united community of earlier times of which Margaret Ashby wrote:

“[Tysoe was] a village of yeoman, craftsmen, tradesmen, and a few labourers – not separate classes, but intermarrying, interapprenticed sections of the community, unified by farming in cooperation, and by as great mutual dependence in other ways. Village affairs were administered through town meetings held in the church vestry, and the villagers conducted themselves not as ‘electors’ nor as ‘parishioners’ but as ‘neighbours”’.

Those days were long gone. Labourers in Tysoe had little option, they could either be out of work or be paid below a living wage. Or they could emigrate. Arch’s preference and his preaching was for migration not emigration, that there was work elsewhere in England to where the labourers could go. His concern was that if emigration went ahead it would cherry-pick the best workers leaving only ‘drones’ behind. Many labourers were less altruistic. They saw no reason as to why they should move to a different part of the country to experience conditions similar to the ones they had already. There was indeed work in the growing industrial centres such as Coventry but these were too far away for commuting purposes.

In the 19th century some 80% of the nation’s food was home-produced. As far as the union was concerned its members had worked the land to provide their country’s leaders with the nourishment to fight wars, to build an Empire and to feed the workers of an Industrial Revolution, and they had been let down badly for their efforts. Nor did they even have a right to vote. Emigration became a more attractive proposition, particularly to Canada from where agents were in Arch’s words already ‘prowling around picking and choosing’. He was right to be concerned – by 1873/4 there are records showing over 170 agents from Canada, Australia and New Zealand touting in Britain.

Arch was aware of a bad precedent. Earlier that year large numbers of people, mostly agricultural labourers from all over the country took little persuasion to emigrate to Brazil. Agents had been set up by the Brazilian Consulate based in Liverpool who, working on commission, arranged passage. It was an unmitigated catastrophe. The Brazilian government needed workers on the vast farms. The English labourers, attracted by promises of good wages and their own land, went in droves. The promises were fake, the work and climate intolerable and the habitation conditions atrocious. One of the agents who persisted in sending folk out was one Edward Haynes of Ratley. His activities make the point that emigration was already actively being touted and pursued in Warwickshire in the early 1870s.

Isaac Featherston, the Agent General based in London, apart from recruiting emigrees for which he had been given target numbers by his government, had also been tasked to find railway workers from Britain to help construct a railway system the full length of New Zealand. Two thousand navvies were sent over in 1872/3 by John Brogden and Sons, Railway Contractors of London on a two-year programme of work. Some men brought their families with them and this indirectly provided an immigration link between England and New Zealand. Many sent encouraging letters home, one man pointing out that he was ‘getting as fat as a pig’ such was the plentiful nature of the food. One member of the railway navvies was one George Hancox, 33, a cobbler-turned-farm-labourer from Tysoe, probably Tysoe’s very first emigrant to New Zealand, who joined the Brogden party sailing in the Forfarshire from London on 12th November 1872, over a full year before The Tysoe 36, with his wife Ann Maria and three children. Their venture is pursued below.

Realising the mood of the labourers, but mindful of the ‘Brazilian mess’ as Arch referred to it, the Union wrote to the Legislative Assembly in New Zealand in May 1873. It acknowledged the extent to which farm labourers were being seduced to foreign parts but promised Union backing for emigration providing certain assurances could be met. The letter told of the plight of the agricultural workers, the words almost certainly coming from Arch’s pen:

“Their homes have, in many cases been wretched in the extreme; their wages insufficient; and their food scant and unwholesome. It has been impossible for them to educate their children; to avoid the miseries of debt; or to make provision for old age; – and the result has been that after years of hopeless toil, during which they have had largely to appeal to public charity, they have been compelled to end their days as paupers in the Union Workhouse.”

The assurances the Union wanted from the Assembly were straightforward. They wanted: (a) proper reception facilities for all emigrees on arrival (b) work to be immediately available and properly paid, (c) opportunities for betterment and (d) free passage. The terms were accepted almost instantly and the agreement published on November 1st 1873 in the Labourers’ Union Chronicle in Leamington, the Union’s nerve centre. This changed the emigration dynamic completely. Within days Featherston sent one of his agents, a man called Charles Carter, to meet Union representatives, and in the following year 1874 no fewer than 37,000 emigrants arrived in New Zealand. The Tysoe 36 have to be seen as an early part of this huge diaspora.

One of the agents at that time working for Featherston was an agricultural labourer called Christopher Holloway from a village near Woodstock in Oxfordshire. Like Joseph Arch, Holloway, was also a Methodist lay preacher with a persuasive oratory. He was asked by Featherston to convene meetings for labourers in Oxfordshire and Warwickshire to be addressed by Featherston’s representative Charles Carter. One of these meetings was in Milton-under-Wychwood and took place on November 4th 1873, attended by over 500 labourers. It seems almost certain that some of The Tysoe 36 would have attended this meeting despite the 20 mile travel involved. Such was the response and the enthusiasm that there was a clamour for application forms. Like Arch, Holloway was concerned that any emigration should not follow the Brazilian model and agreed by invitation of the New Zealand government to join one of the first group of emigrees to New Zealand to witness the veracity of the promises himself. As a matter of urgency Featherston chartered two ships to convey a large number of emigrees at short notice, in barely over a month’s time, to sail from Plymouth to Port Chalmers in New Zealand. To show good faith he invited Holloway to join the group. One of these vessels, the one that carried Holloway, was the Mongol, a 2265 ton steamship, the other being the Scimitar, a sailing ship almost half the tonnage. The Scimitar’s passenger list has survived, but that of the Mongol has not, other than some passenger names in Holloway’s diary, and there may well have been Tysoe names on that list too.

Fig 4. The steamship ‘Mongol’ at anchor in Port Chalmers.

De Maus, David Alexander, 1847-1925 :Shipping negatives. Ref: 1/2-015213-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22451027

Fig 5. Photograph of a painting depicting the Scimitar.

Kinnear, James Hutchings, 1877-1946 :Negatives of Auckland shipping, boating and scenery. Ref: 1/2-015976-B-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22495523

Applicants would have to be under 45 and would need to undergo a medical check. The free passage element had conditions: it was the entitlement of skilled labourers, those unskilled received an assisted passage only. Single women were also encouraged. According to the New Zealand criteria they were to come ‘as domestic servants, milkmaids, seamstresses and future spouses’. They would then have been allocated one of the two ships and given a departure date, travelling at their own costs to Plymouth where they would be accommodated by the New Zealand government in a designated depot.

Transport to Plymouth was arranged by the Union’s General Secretary Henry Taylor and a train carrying 300 emigrees from Warwickshire and Oxfordshire left Leamington at 0800 on December 13th 1873 stopping at various stations. The night before departure The Tysoe 36 all met at the Old Tree (the Elm Tree) to say farewell to friends and neighbours before boarding the train at Banbury next morning, changing trains at Didcot and arriving in Plymouth at midnight on the 13th. Both vessels were scheduled to depart the following day, December 14th, but both voyages were delayed partly due to cargo loading issues in the London docks, but also to several days of thick fog. The depot was ill-equipped for accommodating some 700 people for several days. It was over-crowded, facilities were poor, the air was damp and it seems that emigrees brought in from Jersey and Ireland were carrying measles and scarlet fever which was becoming widespread. Nevertheless, the ships would need to have been signed off by the port’s surgeon as being free from disease. That said, it seems clear that both ships sailed with disease on board despite the concerns of the respective ship’s surgeons which were over-ruled by the New Zealand authorities, with tragic results.

The Mongol eventually departed from Plymouth on December 23rd 1873 arriving on February 13th 1874. The Scimitar left on December 24th and arrived on March 5th, somewhat longer than the steamer, but in a record-breaking 70 days (or 67 from land to land) for a sailing ship. On departure at Plymouth they were given a rousing speech by none other than Joseph Arch himself.

The Passengers

The enormous range of places from where the emigrees had come must reflect the effectiveness of Featherston’s network of agents. If we look through the Scimitar’s list of those in the family accommodation (almost 300 individuals) the most numerous were from Germany (12 families), then from Warwickshire and Berkshire (11 families each), then Oxfordshire (6 families) with smaller numbers from throughout the south of England and the home counties as well as France and Ireland. There were 42 individuals in single women’s accommodation, the most numerous being from Ireland (7), Gloucestershire (6) and Warwickshire and Oxfordshire (5 each). Other individuals included women from Germany, Ireland and Scotland. Where occupations were recorded, 13 were described as servants, one was a housemaid, oner a milliner, one a nurse and one a dairymaid.

There were 93 individuals in the single men’s accommodation, the largest cohorts being from Ireland and Germany (15 each), Oxfordshire (11) and Warwickshire (9) with others ranging from Scotland, the south of England and Jersey. The majority of those with named occupations were farm labourers (30), labourers (24) or ploughmen (3) with single entries showing a remarkable breadth of skills – blacksmith, stonemason, waggoner, slater, baker, fisherman, shoemaker, wheelwright and carpenter.

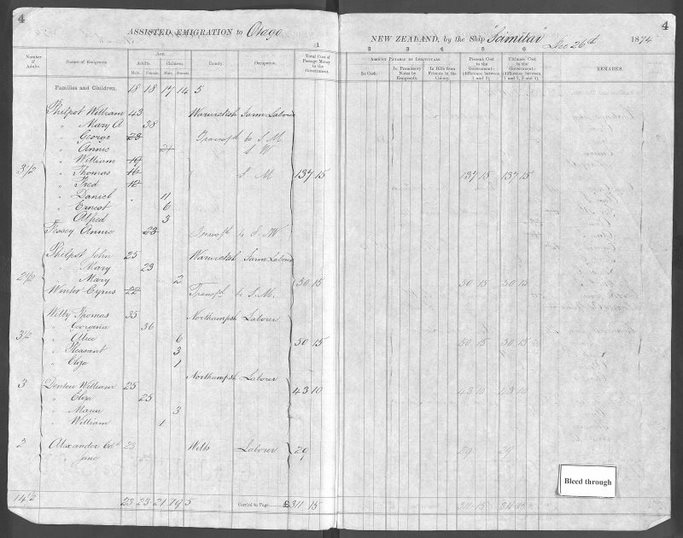

The passenger list gives names, ages, occupation (if known) and county of origin, but no specific village or town. The calculation of the Tysoe contingent was therefore arrived at by listing the names recorded as being from Warwickshire and checking them against other records such as the parish register. The final number was 36 although some sources which took the passenger list at face value give the number as 43. This was because seven Tysoe passengers were moved from family to single accommodation on board and were counted in twice. The final number is 36 although this does not preclude others whose names may have slipped under the documentary radar. In fact after the meeting at the Old Tree the night before departure a plaque was set into the wall of a nearby house which is said to have commemorated the 43 Tysoe-ians who emigrated. This may have resulted from the same error. Alternatively, it may have included some of the other Warwickshire passengers born in other parishes who settled in Tysoe between censuses, or possibly seven who boarded the Mongol. The registration book shows that the cost of the journey was £50-15s-0d. The ‘Amount paid by emigrant’ column was, in all Tysoe cases, blank indicating that their fares had been paid either in full or in part by the New Zealand government with any shortfall being picked up by the Union.

Fig 6. Page from the passenger log. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DR69-LHQ?i=11&cc=1609792

There were six families and a number of individuals from Tysoe. As was often the case in remoter villages much intermarrying had taken place and most of the families were either directly or indirectly related to each other. Mark and Ann Fessey who travelled with 3-year old Thomas and with Mark’s sister Annie who was a servant to the Philpot family (below) were from Middle Tysoe. Mark had only recently been released from gaol having been convicted of manslaughter after a boxing match. The Lynes family from Upper Tysoe consisted of Henry, a farm labourer, Maria his wife, their six children Mary Ann the eldest who was a servant, Sarah Ann, David, Joe, Betsy and Willie. John Philpot and his wife Mary came from Upper Tysoe with their two-year old daughter Mary. They were undoubtedly related to the other Philpot family from Upper Tysoe headed by William, his wife Mary and their eight children of whom George, William, Thomas, Fredrick and Annie were all of working age, Annie being a servant, as well as three youngsters Daniel, Ernest and Alfred. The father, William Philpot, had worked as a farm labourer on the Compton Wynyates estate but, when the Union was formed, the Marquis had refused to pay him Union rates of pay. He was 49 years old at the time of the 1871 census (ie 51 at the time of sailing) but his age was conveniently reduced to 45 (the maximum age permitted) to allow the family passage. Another appendage to the Philpots appears to have been Cyrus Winter , also a farm labourer from Upper Tysoe who was the brother of Mary Philpot.

The Styles family came from Lower Tysoe, Alfred a farm labourer with his wife Jane and three children George, Sally and Emily. The Townsends were also from Lower Tysoe, Matthew, a farm labourer, travelled with his wife Elizabeth and their three children Lucy, Amy and Frank.

The Voyage

The boat that took them was a sailing ship, not a steamer like the Mongol. The Scimitar was a rigged vessel, built in Hull in 1863 and had spent her early years plying between London and India before being sold to the New Zealand Shipping Company in 1873. It carried cargo as well as passengers, on this occasion some 550 tons of iron railway materials. It was a ‘clipper’ to all intents and purposes with a raised poop deck at the stern and a raised forecastle at the bows with painted gun ports to deter pirates. The Master was Captain James Fox, an experienced mariner who had made the New Zealand run on many occasions before. The First Officer, Robert Winder, also held a Master’s ticket as was usual for large ships on voyages of this kind.

The Scimitar had a crew of 46 some of whom were dedicated to looking after the passengers, of which on the run in question numbered an astonishing 430. A small number of these (less than 10) were in Saloon Class. It was often considered de rigueur for these well-to-do passengers to sketch and paint during the voyage although no artworks seem to have survived from this particular voyage. They were separated from the remainder who were in steerage – this was the large space between decks almost the full length of the ship. It was effectively an open area with temporary subdivisions and bunk beds separated by curtains. To say it was crammed would be an understatement. There was a separate area for single men, one for families, and a secure area for single women. By ‘secure’, access to it was vetted by a matronly figure from among the emigrants to ensure that Victorian propriety was properly maintained. Single women were also restricted to the poop deck for fresh air and segregated from any males for the entire voyage. Food was provided for the emigrees in the form of salted or dried produce and served in communal areas; they were divided into groups each with a ‘mess captain’ who collected food from a central kitchen at meal times. Those under twelve years received half the amount. By contrast passengers in Saloon Class enjoyed fresh meat from an assortment of animals kept for slaughter in pens on the deck and were served by stewards. When the weather was good emigrees were permitted on the open deck. The vessel was also obliged to include a small surgery and hospital manned by a surgeon superintendent. On the Scimitar this was Dr W H Hosking. All steerage passengers were required to be in the bunks by 10 pm.

Extract from the Captain’s Log January 5th 1874:

“At 4 am Mr Winder the Chief Officer called me to report the death of the little boy Brown in the fever hospital that had been suffering from scarlet fever and measles combined. He expired at 3 am and we buried him at 8 am. The hospital being full and the measles rapidly spreading on board. We have another single girl down making four in hospital and some other children. Every precaution is being taken by Dr Hosking assisted by myself to prevent the disease from spreading.”

Two days later the situation had become worse.

Extract from the Captain’s Log January 7th 1874:

“At 5 am Mrs Smith’s baby died. We buried it at 3 pm. It died of congestion of the lungs. The measles is rapidly spreading , we have another case of scarlet fever and measles combined now in the hospital. A little girl by the name of Bennett. The hospital is well filled now, principally with measles. Everything that can be done for their comfort is done. The ship is getting swarmed with lice and we have several complaints from the clean and respectable passengers about them.”

As January progressed the sickness spread further. Unusually, the Captain had ordered animals intended for the Saloon passengers to be killed so that the sick could have a better diet of mutton broth and potatoes in place of the predominantly dried food normally supplied. More children died from convulsions, measles and scarlet fever as the voyage progressed, some families losing more than one child. Among these was the Carey family from Limerick who lost 3 year-old Mary on January 15th. Sadly, her two elder brothers, James aged 5 and John aged 7 were also to die on board before the month was out. The Townsend family from Lower Tysoe were among those who also suffered losses, little Amy Townsend aged two passed away on January 24th and her 10-month old brother Frank two days later. All the deceased were buried at sea within a few hours of death, as was required to prevent further disease. One of the sailors, a friendly man the children all called ‘uncle’, was deputed for this task. Each child was wrapped in a union jack and taken to the side where they were committed to the waves after a short service given by the Captain. By now the small shipboard hospital was unable to cope.

Extract from the Captain’s Log January 19th 1874:

“The scarlet fever, measles and diarrohea and ulcerated sore throats are still prevalent and new cases crop up daily. It is grief to see the quantity of children suffering in the main compartment. In about every third bunk a child is laid . . . I do not know how many cases we have of sickness just now. Eunice Tombs aged 10 months died at 10 am and we buried her at 1.30 pm. We served out fresh mutton and fresh potatoes to the sick at noon.”

During the voyage the Doctor’s log recorded 100 cases of measles, 50 of scarlet fever, 120 of severe diarrhoea and cases of mumps beyond counting. By the time New Zealand had been reached the Captain had buried 26 emigrants, all but one a child. But there was some consolation, four babies were born during the voyage, one of them to Mrs Carey whose other three children had died earlier. Other deaths were no doubt avoided by the Captain’s insistence on providing the sick with better food. It was to this end that decided to make an unscheduled stop at Tristan da Cunha on January 31st.

Extract from the Captain’s Log January 31st 1874:

“At 4 pm we came up with the west point of Tristan da Cunha. We came up with the settlement and Mr Peter Green the Governor and 12 men came off bringing 11 sheep, 3 pigs, 2 geese and 18 bushels of potatoes, fresh eggs, cranberries and cape gooseberries. I bartered for the lot. I found Mr Green a very nice old Tar . . . He has been on the island 37 years, married and his family are grown up and married. They have 18 families on the island numbering about 90 souls. We supplied them with some medicines, books for their children and sundry necessaries. We bid them adieu at 7 pm . We had them on board about two hours”.

Sadly, the fresh food was too late to save 7-month old Emily Styles from Lower Tysoe who passed away on February 10th.

Captain Fox had other issues to contend with apart from scarlet fever and measles. Early on in the voyage he had a minor mutiny among some of the emigrant menfolk who objected to having to help up with the coals to fire the ovens. Another group objected to cleaning, and he had to arbitrate in a heated argument between nurses and cooks, added to which a group of dissenters (non-conformists) insisted on worshiping separately on Sundays. He had a notable issue with an 18-year old man, Richard Kelly, from Waterford who was difficult and argumentative and whom the Captain referred to as ‘Mad Kelly’ throughout the remainder of the log. Another troublemaker to tax his patience was a single mother, Mrs Reynolds from Armagh who, among other things, continually issued death threats to other passengers. She was a persistent nuisance and on February 15th the Captain wrote:

“I think she is a civil mad woman, jealous of everybody and excessively greedy. I am getting tired of trying to please her”.

Issues of discipline were dealt with swiftly: a boy who hit a constable with a broom handle was placed in the starboard lifeboat as punishment, the ship’s carpenter who was caught “skylarking with the single women” was subsequently confined and one of the sailors was clapped in irons until midnight for a particular but undefined misdemeanour.

One of his more general concerns was with the attitude of some of the emigrants. “I am convinced”, he wrote, “that a great many of the children are badly nursed by their parents although they have liberal supplies of medical comforts and convenience”. On another occasion he complained that “. . we have been around arranging about the cleaning today amongst the married people who seem confoundedly stupid and they require lots of bawling to get the work done”. He was also concerned by their apparent selfishness over the special diet issued for the sick in that “those that stand no need for it are scheming to try and get it”. He was not one to hold back on criticism. On January 24th he wrote “We have some miserable dirty people among the families. The Germans are keeping very clean and orderly this voyage. I think we must have got hold of a superior lot of Scandinavians this time. They are quite an example to our English emigrants for cleanliness and attention to their children”

The longer the journey continued the greater the number of petty arguments that arose. On Feb 18th the usually tolerant and diplomatic Captain wrote that he wished the journey was over. Notwithstanding all this, Dr Hoskin remarked on safe arrival in New Zealand, that in addition to these problems, given that the Captain officiated at all Sunday services, one or two baptisms, a marriage and 26 funerals, there was enough work in that alone to keep a Parson employed.

Despite these ongoing problems George Philpot from Upper Tysoe wrote home an upbeat letter about the voyage published in the Labourers’ Union Chronicle in May 1874.

“We have one of the best captains that ever crossed the ocean. I have not heard a bad word from him all the voyage. The first mate is a particularly pleasant man, and all the sailors, too; they often come down and join us in a spree at night, when they are not on watch. We have had several concerts while on board, at night…. Charles Fox is our captain’s name, and a good man he is; it grieves him very much to lose so many children, all small ones; he has got no children himself, his wife is a nice woman, too. The captain has given the children tea and cakes a time or two, and brought plums and nuts out to scatter among them. Anybody who thinks of coming out here need not be afraid of having a short allowance of grub, for there is plenty of victuals, quite as much as you can eat; there is pudding three times and rice twice a week”.

It seems the Captain did his best to deflect attention away from the sickness and death on board. On New Year’s day he issued a supply of ale and stout to those who wanted it. Books were available from the ship’s library and he held a party and a concert after he had performed a marriage ceremony on the ship between two Norwegian emigrants. He arranged for a dance on the poop deck for single girls and, when the ship crossed the equator on January 16th many of the crew dressed up as Neptune or Amphitrite to mark the occasion, as was traditional. As the Scimitar sailed through the Indian Ocean the sailors caught some albatross to entertain the passengers. These scenes clearly caught the imagination of George Philpot who describes them in a letter to his grandmother in Tysoe early after arrival on March 7th 1874:

“We had some fine games at night. Some of the sailors who had never passed the equator before were daubed with grease and tar and then shaved as they called it. They were then thrown into a butt of water and washed. Previous to this the ‘King and Queen’ of the sea come aboard dressed very fine as you would suppose. . . . On Thursday 12th of February they caught nine great birds. Their wings when spread out are ten feet in breadth, and the sailors tell us they have seen them 15 feet in the wing, and standing a yard from the ground. There was one of these birds sent down to each house and they parted the feathers among the people”.

Later in February the Captain arranged a children’s party despite having buried another child earlier the same day.

Extract from the Captain’s Log February 9th 1874:

“We gave all the children that were able to come, a tea, in the single girl’s compartment. Mrs Fox had sundry book and toys which were distributed according to the school master’s report for the school. Some were run for and we have sundry sports from 3 pm to 4 pm when the snapdragons ended the sports. Just when they were cheering those that had been entertaining them before they broke up a squall was on the ship rolled to windward and a tidy knot of a sea came on board and drenched the greater part of them much to the disgust of some of the parents but to the delight of the larger boys and girls”.

The boat sailed into Port Chalmers, Otago on March 5th flying the yellow flag that indicated disease on board. It was towed to a quarantine mooring from where the sick and their families were rowed out to quarantine accommodation in the ship’s boats. It was not until March 21st that the Scimitar was allowed to unload its cargo and set the rest of its passengers ashore. On the 26th March the Tysoe group were transferred to a steamer called the ‘Wanganui’ together with immigrants from other ships and arrived two days later at Bluff near Invercargill where they were eventually to settle, at the very tip of South Island.

Fig. 7. General map of locations.

Their arrival was reported in the Southland Times on March 31st:

“The expected arrival of the immigrants . . . brought together quite a crowd of townspeople at the railway station on Thursday evening. The newcomers, mostly married men with families were, we fancy, rather taken aback to find themselves objects of so much curiosity. Poor souls, they looked fagged, jaded and anxious as they marched up to the Immigration Barracks . . A good supper and a sound night’s rest, with breakfast to match, made a wonderful difference in their appearance the following morning. The wan, depressed looks were gone – the children were tided up, and everyone seemed comfortable and hopeful . . . . We may add that they appear to be a good hardworking people, and likely to prove a very useful accession to the population of the district”.

It was in the Immigration Barracks that employment matters were settled, as the Union had insisted. Two days later all the families and the single men that had arrived were satisfactorily contracted and started new lives.

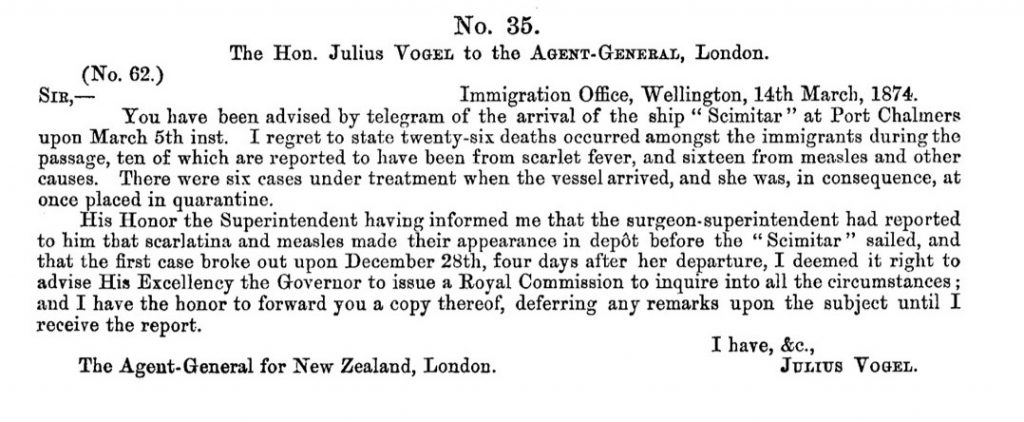

Fig 8. Notice of Public Inquiry.

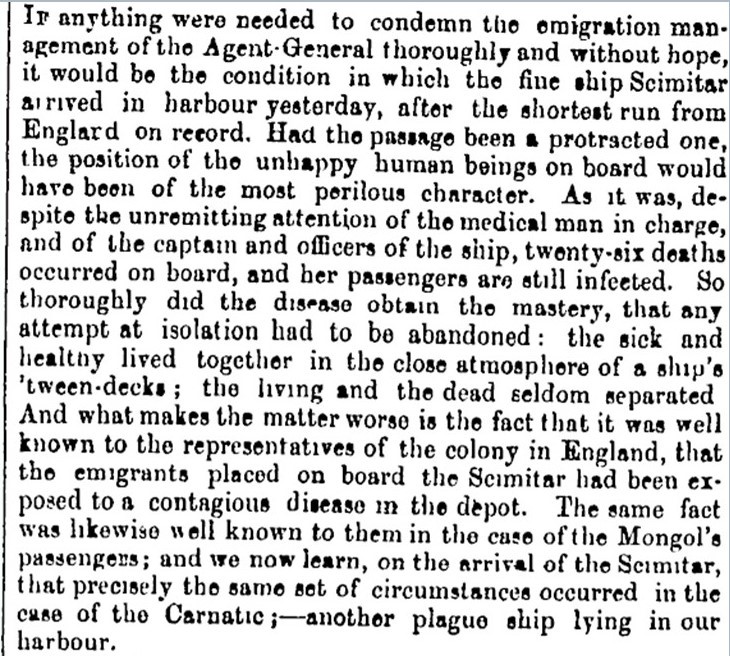

However, Captain Fox’s work was far from over when the Scimitar had unloaded its cargo and passengers and was declared out of quarantine. In view of the sickness and deaths on board both the Mongol and the Scimitar a Royal Commission Inquiry was established. Captain Fox and Dr Hoskin came out of it tolerably well but the main onus of blame fell squarely on the port authorities at Plymouth for allowing infected persons to board contrary to Dr Hoskin’s opinion who described it at the Inquiry as ‘a rotten system’. A number of passengers claimed to be disease-free when they were manifestly not. Even the New Zealand Prime Minister described it as a ‘floating pest house’. There was criticism too of the inadequacies of the Plymouth depot, the standard of food on board, the sanitary conditions and the hygiene of some of the passengers who should not have been allowed on the vessel. Public opinion in New Zealand was aroused and the Otago Daily Times on March 6th 1874 carried a piece lamenting that on board the living and the dead were seldom separated.

Fig 9. Otago Daily Times March 6th 1874

On March 18th the same newspaper demanded a review of immigration arrangements in general and of Isaac Featherston’s role in particular:

“The Agent-General is to blame for not exercising that strict supervision of his subordinates which his position demands of him. Better far that the much-needed supply of settlers for the colony should run short for a while than that the unhealthy and weakly should be foisted upon us. We object to the sweepings of the cities and towns of the old country”

Editorial comment in the Otago Witness on March 21st was even more condemning:

“One hundred babes with not a pound of sago between, launched on a three month voyage is a condition of things likely to eventuate a murder. It is little short of butchery to ship out a lot of young children under five years of age.”

Health issues aside, the newcomers did not entirely endear themselves to the existing population. Newspaper reports at the time include references to drunkenness and disorder, and in one case a murder by one of the emigrees from Scotland.

New beginnings

The details of what the families did in the early days are sketchy, but give a broad idea of their new lives. The Philpots were employed in an area called Waikeva Plain, just outside Invercargill, where they had soon earned enough to buy 25 acres of bush which they were able to clear and farm. Annie Philpot wrote to her grandmother back in Tysoe in December 1875 keeping her informed of events.

“Father and the boys are busy now, they are clearing the bush and cutting up the firewood for sale. We have a nice crop of English grass just coming up. . . . Our cow is tacked out now in a neighbours paddock because father has not finished fencing the section. Father is thinking of buying two more cows in the spring, and when the section is cleared and sown in grass, we shall most likely have nine or ten cows. . . The bushland is very rich; there area great many large black pine trees, besides Maneuka and Taharrs, each of these is valuable for firewood in town.”

Granny may have been rather nonplussed by the next paragraph:

“We have often felt sorry for you to think of the long cold winter you were getting and many a poor old woman at Tysoe could not afford a good fire to warm her. I have often thought how I would like to give them a seat near our large fire of pine logs and a meal of beef and mutton but it is too far away.”

As ever, there was a good Christian sentiment to round off the letter:

“Mother says she would like to see you (and so should we all) but we cannot expect it in this world, but in a fairer one we will. My Dear Granny, pray for us that we may so pass our time in our earthly home, that we may not lose sight of our Heavenly home. There we shall meet, my dear Granny by God’s will.”

The Philpots with their six males of working age became a well-established family in the area and performed exactly what the New Zealand government wanted, taking new land and building up the colony. As the family expanded and their occupations diversified they appeared to have kept in touch and a New Zealand reunion that took place in 1999 attracted no fewer than 107 Philpots descended from the original family that crossed in the Scimitar, many a far cry from their original farming stock.

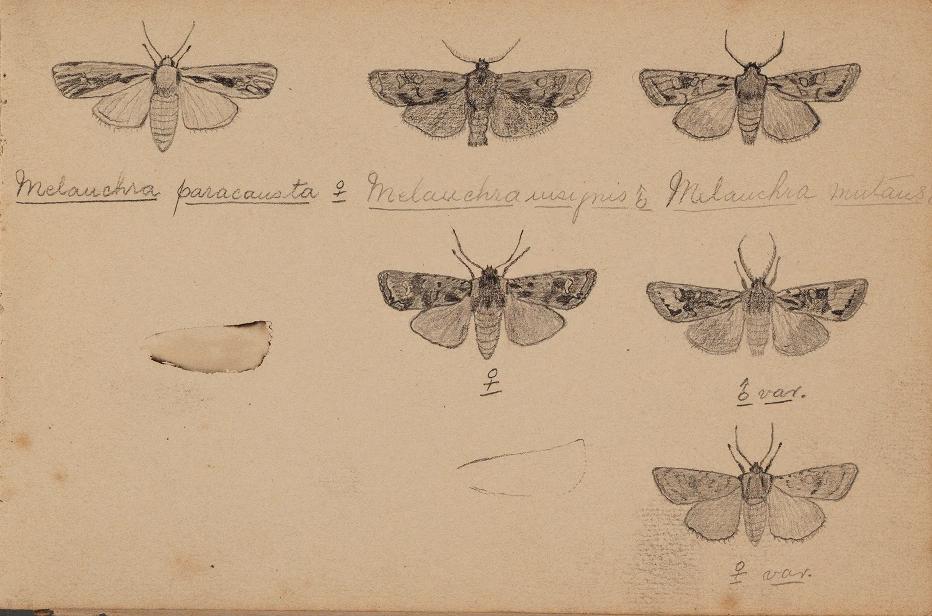

Of particular note is the career of Alfred Philpot who was only three years old during the Scimitar’s voyage. After leaving school in New Zealand he worked as a condenser in a milk factory and in his spare time became interested in insects, moths in particular. Such became his knowledge and understanding that he was appointed curator of the Southland Museum in 1917 and received international recognition for his work. He joined the staff of the Cawthorn Institute in Nelson as an entomologist where he named new species and became a world pioneer in the study of moth genitalia, eventually publishing profusely and becoming a fellow of the Entomological Society of London.

Fig 10. A page from one of Alfred Philpot’s sketch notebooks.

Auckland War Memorial Museum. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/59897049#page/7/mode/1up

One of the Philpot ‘family’ included Annie Fessey, a 23-year old servant to the family. She had lived with her parents, two siblings and a brother’s wife and their three children in what must have been a packed household in Middle Tysoe. No wonder she chose to emigrate. She travelled with another brother, Mark, his wife and 3-year old Thomas. Very little seems to be known of their early activities but interest in them stems from the marriage of Mark’s sister, Mary Hannah Fessey from Tysoe who married the artist William Matthison in 1878. They lived in Vicarage Row in Main Street, Middle Tysoe, for several years in the 1880s during which time Matthison painted numerous local scenes several of which were sent to the Fessey and Philpot families in New Zealand to provide memories of Tysoe. This explains why so much of his work has been found on the other side of the planet. Matthison died in 1926 and several were sent by his widow Mary Hannah. In one of her letters to her niece Mary in New Zealand dated November 13th 1935 she refers to just having packed two paintings for her, one of a cornfield at the bottom of Old Lodge, the other of Compton Wynyates. Others that are known to have been sent include pictures of the Old Tree, the old windmill on Oxhill Road and views of Main Street. Another was of St Mary’s church, Tysoe which she sent to her nephew William Philpot in New Zealand when she was almost 80. The letter emphasises the Tysoe connection:

“Auntie Katie’s dau[ghter] has just written to me to say that the pictures have been sent off this week. We thought you would like to have them as they are some of Uncle Matthison’s work, and a memory of Tysoe, and also the church where your father and mother were christened and married, your granny and grandfather baptized, confirmed, married and buried there. All your aunts and uncles, including myself were baptized at the dear old font and confirmed at the same chancel steps”.

Nostalgia apart, her advice on how to treat the paintings would make any fine art conservator wince in absolute horror:

“The pictures are very dirty, but if you rub them well over with a cut raw potato and then wash gently over with a soft sponge or rag with lukewarm water and dab dry with a very soft rag or cloth, you will find them much better. But do not rub hard. If you find in one of your towns an artist’s colour shop, get a small bottle of Copal Varnish and a very soft sable brush you might spread a very thin film of varnish all over. It would brighten up the colours”.

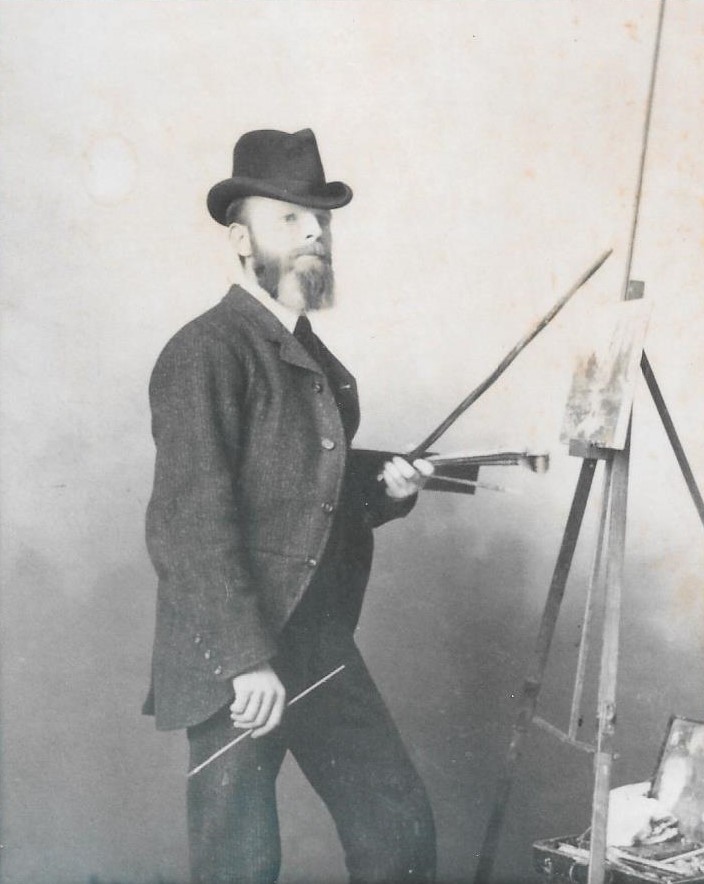

Fig 11. Photograph of William Matthison. Source unknown.

George Hancox from Tysoe who came out with Brogdens for railway work on the Forfarshire, wrote an enthusiastic letter home on 15 March 1873 which may have persuaded others to follow him:

“We went to work on Monday morning and we have been working all the week eight hours a day, no longer. The second day, when we came home from work, there were two legs of mutton in the boiler for our supper, this seems enough to make a man dance after a hard day’s work…. There is plenty of chance in this country. Farmers are advertising for farm labourers from 60 to 100 pounds a year and their living for man and wife to do the cooking. We are not obliged to work for Brogden at all at railway making; we can go where we like; he only wants us to pay 5s. per week, and that is not much in this country. We shall be able to pay that soon if God gives us our health and strength. . . . Tell any of my friends that living is cheap, and Jack is as good as his master. We have a Wesleyan Chapel close by; I went yesterday and it seemed as though I was at home, it was good to be there. There are no Primitives here, but I shall find some before long…. Tell any of the Tysoe men that this is the country for any steady, industrious men; but they can come out by the Government cheaper than the way we came…. Please give my love to T. Hancox and other friends and tell him I will write to him as soon as I can.”

Brogdens had seriously overestimated the numbers of navies required for railway work, in fact they only needed about one quarter of the 1300 or so recruited. George was one of the lucky ones to be employed in that he was guaranteed two years of work as part of the contract. Many of the others found work locally and went native providing a considerable, if unofficial, boost to colonisation. The Hancox family lived in Wellington and George took work as a labourer when his contract with Brogdens was over then, in 1882, moved to Auckland and took up a job with a timber company before moving his family up to Te Karoa at the far north of the country a few years later. They purchased 50 acres of bush and built a small shack to live in as they developed the farm. He described it as ‘beautiful, bush-clad rolling countryside’ rich with wild boar, pigeons and fish, where he began the difficult task of clearing massive virgin bush and planting. By the time of his death in 1915 the house was substantially larger, the farm well under way and it remained in the family for a number of years. The current Hancox family have produced two privately printed books which give an amazingly detailed family tree and the wider context of their lives in both Tysoe and in New Zealand.

The Union representative, Christopher Holloway, who had arrived in the Mongol had a duty to report back to his Union executive to inform them of conditions and the potential there. Having talked to many immigrants and their employers and seeing life at first hand he was unequivocal in his praise.

“I have associated with the great landed proprietors, and with the less affluent settler who is steadily advancing upwards to a more prosperous position . . . I have come to the conclusion that any of our labourers, gifted with temperate habits, such as sobriety, industry, frugality and perseverance may in the course of a few years become occupiers of land themselves”

This reflects a strong Methodist influence which also embodies an anti-establishment element and represented the formal response that the Union wanted to hear. However, it was the details of wages that were needed to inspire potential emigrees. These were published in Holloway’s letter to the Banbury Guardian on July 29th 1875 giving news of individuals who had emigrated on the Mongol.

“I found that sober, strong, able-bodied men, farm labourers and navies were actually receiving 8s per day for a day of 8 hours. Ploughmen were getting £1 per week, shepherds from £35-75 per year . . . John Gibbs of Tackley, a working man, went out with me in the Mongol to the province of Otago, with his wife and six children and a letter he recently sent to Tackley [he wrote] ‘I am getting 8s a day for 8 hours work, and my son 15 years of age is getting one guinea a week. I have bought a piece of land, and expect to have a house built upon it very shortly’. . . John Smith, a ploughman went out with me in the Mongol. When I visited him in the province of Canterbury he was getting a pound a week and everything covered. . . John Woods of Steeple Aston, tailor, went out in the Mongol with me settled in the city of Christchurch and was getting 11s a day for eight hours work . . . Well – I draw the arrangements between the conditions of the farm labourer at home who has 10s a week and his brother labourer in the colonies at 8s per day, I leave it to the farm labourers themselves . . . to judge which has the preference”.

To make the point, by 1881, seven years after arrival, William Philpott had freehold land worth £390, Alfred Styles land worth £123 and Matthew Townsend land worth £180. His only surviving child from the voyage Lucy eventually became married and had ten children. The Lynes parents also ended up with ten children, although where they settled appears to have eluded the record. However, the new living did not appeal to everyone. Cyrus Winter, who was mentioned in a letter from Annie Philpot to her grandmother and who was working with her brother Will in Longbush, returned to Tysoe a few years after. He may have been the person alluded to by Margaret Ashby as the man who appeared back in Tysoe from Southampton pushing his belongings in an old wheelbarrow.

Cyrus Winter would have returned to find rural England still recovering from the depression of the 1870s, there was little work in the villages and farmers were doing all they could to drop wages despite the influence of the Union. Those who were in work were hard pushed to hold out for a wage of 13 shillings a week, the highest in 1882 being 15 shillings, still well below New Zealand levels. Disraeli, back in power, had refused to reinstate the Corn Laws despite poor harvests and many farmers found no point in planting crops. There was little work, tied cottages were empty and dilapidated, and living conditions were wretched.

Ashby’s descriptions of local villages published in the Warwick Advertiser in 1883 depict a landscape peppered with tenantless farms and neglected fields. Ashby described Tysoe as a picture of ‘beauty and peace’, but one which veiled the ‘misery and scars of poverty and strife’. Population figures in the parish had slumped 11% between the census dates of 1871 to 1881, partly due to emigration (in fact seven more families emigrated in 1874 on a vessel called The Crusader, including another branch of the Hancox family); there were grumblings over the Parish assisting the passage of another family of nine to Canada, and of cottages being denuded of blankets and sheets for those who chose to depart. Many of the village girls were becoming employed in service in urban centres such as Banbury and not returning. There was a strong opinion that those who emigrated were the ablest and most hard-working families, leaving Tysoe commensurately poorer as a result. Joseph Arch had prophesied that emigration would leave behind a countryside of ‘only boys and old men’. But Tysoe was better off than some. The population of Pillerton had fallen by 38% and Oxhill by 27%. Ashby described Whatcote as being ‘half-deserted and half lost’, adding, it was ‘difficult to imagine a village socially lower’. It seems that those who had emigrated were well out of it. There was also the need for long awaited land reforms. The Allotments Bill was still well in the future and the Tysoe Allotments and Smallholdings Association formed in 1880 had to wait another three years before Lord Northampton finally allocated them fields. No wonder those fields were called ‘The Promised Land’. This was the unhappy Tysoe to which Cyrus Winter returned pushing his belongings in a wheelbarrow. By contrast, those in New Zealand were owning land, becoming independent, and enjoying a degree of upward mobility. Perhaps this was because they showed initiative and were hard working. The same opportunities and rewards were simply not available to them in Tysoe.

The Scimitar made several more voyages from England to New Zealand carrying a total of some 1500 emigrees. She was later renamed the Rangitiki. Her rigging was reduced to that of a barque in 1889 and she was disposed of ten years later with the advent of steam and sold to Norwegian owners who renamed her Dalston. She was subsequently sold to French owners, renamed Paul Bouquet, and taken to Noumea where she ended her life as a hulk.

Fig 12. The sailing ship Rangitiki.

De Maus, David Alexander, 1847-1925 :Shipping negatives. Ref: 1/1-002380-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22821987.

Further reading

Arch J. 1898. From Ploughtail to Parliament: An Autobiography by Joseph Arch. Ebury Press (1986 edition).

Arnold R. 1981. The Farthest Promised Land: English Villagers, New Zealand Immigration of the 1870s. Wellington, Victoria University Press with Price Milburn.

Ashby A W. 1912. ‘One hundred years of Poor Law administration in a Warwickshire village’, in Vinogradoff P (ed.) Oxford Studies in Social and Legal History, Vol III, Elibron Classics, (facsimile edition), Oxford 2005.

Ashby M K. 1961. Joseph Ashby of Tysoe 1859-1939. London, Merlin Press (1979 reprint).

Beith M A. 2019. No Gravestones in the Ocean: the emigrant ship ‘Scimitar’ 1873-1874, New Generation Publishing.

Horn P L R. 1968. ‘Christopher Holloway: an Oxfordshire Trade Union Leader’, Oxoniensis Vol 33, 125-136.

Langley A (ed.). 2007. Joseph Ashby’s Victorian Warwickshire. Brewin Books, Studley (edited compilation of Ashby’s contributions in the Warwick Advertiser 1892-93).

Luntley M. 2021. ‘Carry us away . . . Migration to Brazil – Warwickshire Agricultural Labourers 1872’, Warwickshire History XVIII, 3 149-162.

Knight R. & Wilson F. 2003. From Tysoe to Karoa – Over Yonder. Pioneer Print, Paraparaumu, New Zealand.

Quinault R. 2004. Landlords and Labourers in Warwickshire c. 1870-1920, Dugdale Society Occasional Paper 44.

Wilson W. & Henderson A. 1999. Our Family Tree: George and Ann Maria Hancox. Privately Printed.

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this paper various people kindly provided information and material, notably Kevin Wyles who has carefully collated documents over the years and maintained correspondence with families in New Zealand, and Carol Clark who undertook the mainstay of necessary family and local history research. Other material and support was given by Nick and Julie Butcher, David Freke, Jacqui Franklin, Jane Prue, Doreen Smith and Joy Tangney. The collections of the National Library of New Zealand and the Auckland War Memorial Museum are gratefully acknowledged.

John Hunter for THRG