Memories of Tysoe and Compton Wynyates

Contents

Preface

Early Life in Tysoe

Working in Birmingham

Back to Tysoe

Married Life

Wartime Experiences

Returning to Civilian Life

Starting Work at Compton Wynyates

Retirement

Addendum (1)

Addendum (2)

Addendum (3)

Addendum (4)

Preface

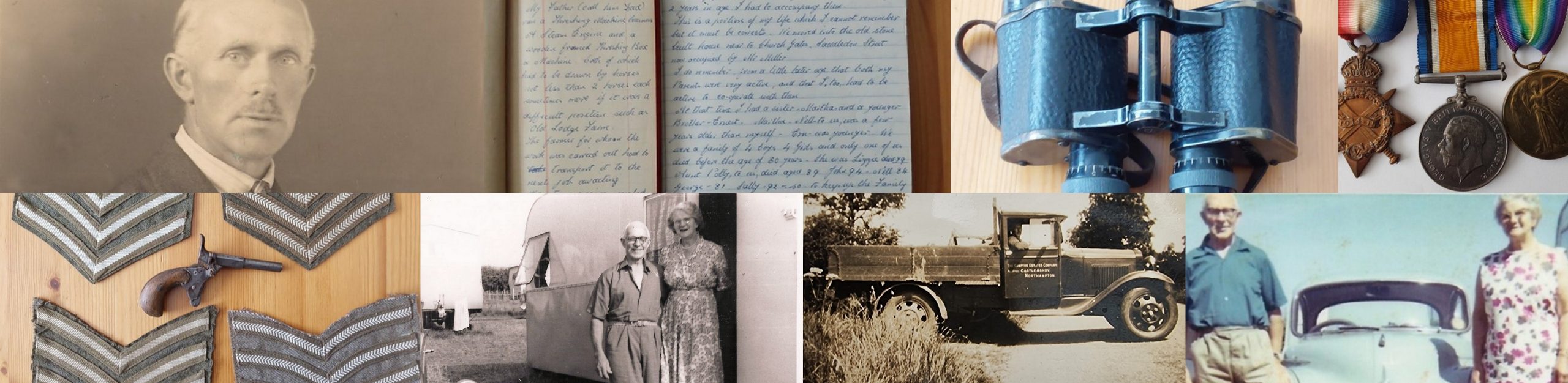

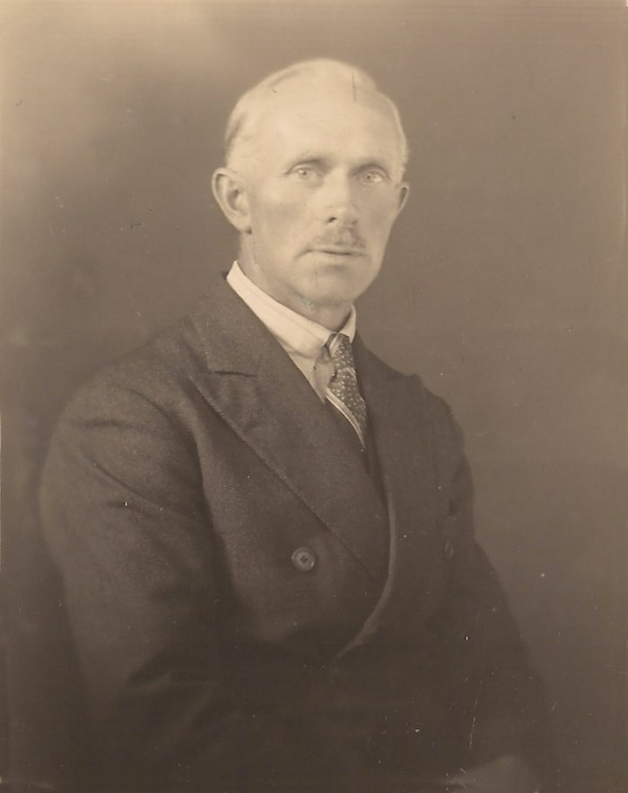

In later life, my grandfather, Francis James Lomas, wrote down his life story and gave it to me. It is, of course, something that I treasure. His writing offers a glimpse of life in rural Warwickshire during the latter part of the 19th Century and much of the 20th Century. He was of the generation who fought during World War One and some of his experiences of that time are also included.

The memoir is written in quite a personal style, and parts of it are addressed to me, with references such as ‘your Granny’. It was written down in two notebooks, and there were some duplications and later additions. The sequence of events is not always clear and so a few sections which were added later by him have been included at the end.

Grandfather spent most of his working life at Compton Wynyates House and, amongst many roles, eventually became a visitor guide. The house is no longer open to the public.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Angela Webb who spent a considerable amount of her valuable time deciphering my grandfather’s sometimes difficult to read hand written notes and putting them into a readable format.

I would also like to extend my gratitude to Carol Clark who continued to work on my grandfather’s story adding illustrations from photos supplied by myself which has really brought the story to life.

The whole process has taken more than a year but is now something to be proud of and I just hope anyone reading this story enjoys it as much as I did.

Alan Lomas

Autumn 2023

Early Life in Tysoe

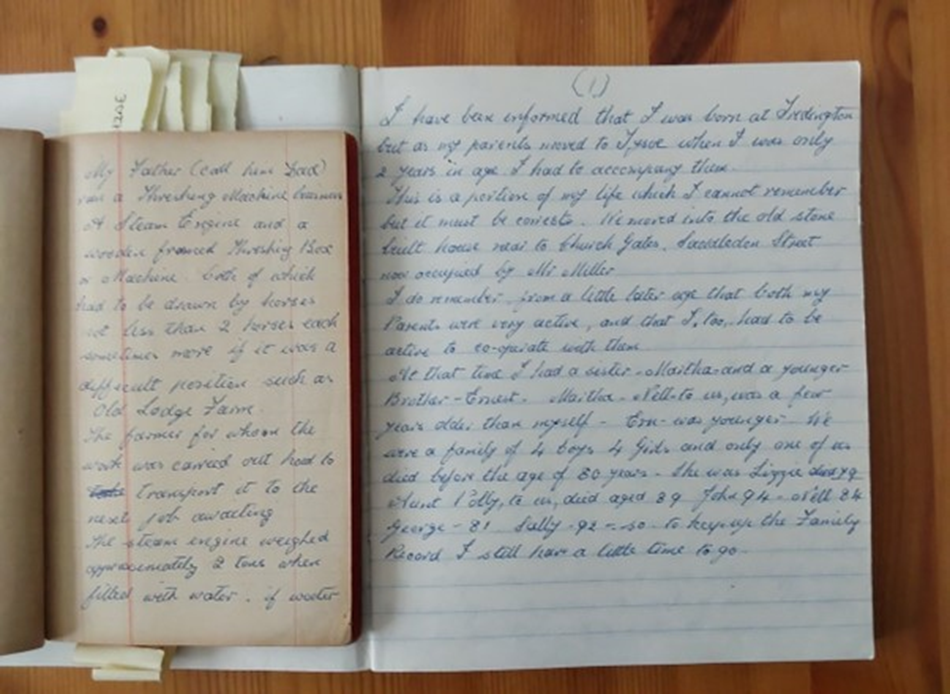

I have been informed that I was born at Tredington [James Francis Lomas, son of James and Laura Lomas, was baptised at Tredington 29 June 1890, per parish register] but as my parents moved to Tysoe when I was only two years of age, I had to accompany them. This is a portion of my life which I cannot remember but it must be correct. We moved into the old stone-built house near to Church Gates, Saddledon Street [currently known as Chamfered End], now occupied by Mr Miller.

I do remember, from a little later age (five or six years or so) that both my parents were very active, and that I too had to be active to co-operate with them. At that time, I had a sister, Martha, and a younger brother, Ernest. Martha, ‘Nell’ to us, was a few years older than myself. Ern was younger. We were a family of four boys, four girls and only one of us died before the age of 80 years. She was Lizzie, died 79. Aunt Polly, to us, died aged 89, John 94, Nell 84, George 81, Sally 92. So, to keep up the family record, I still have a little time to go.

My dad ran a threshing business, working for local farmers in Tysoe, Oxhill, Whatcote and round about. He ran the steam engine and a wooden-framed threshing box. Both of these were horse-drawn, usually two each, sometimes three or more if it was a difficult place to reach, such as Old Lodge Farm. My dad was the steam engine driver and his mate, Sam Reason, was the feeder to the threshing machine. The farmer for whom the work was being carried out, had to transport the threshing tackle to the next job awaiting. The steam engine was, I think, about two tonnes in weight when filled with water, half a tonne less when empty. The farmers then had to supply enough coal/wood to light the fire, water to fill the engine and the engine driver and his mate were also fed by the farmer during the time they were threshing, or paid two shillings and sixpence per day for their keep.

It took a gang of men, about eight, to carry out this threshing business. One to put corn on to the machine usually in hand-tied sheaves, three to tie up the straw as it left the machine, one to take away chaff and earings??, one to attend to sacks of corn, one to put corn for the feeder, one to untie the sheaves. Then there was the building up of ricks etc. This job was usually a wintertime occupation and gangs of odd men kept in touch and would follow the machine and were paid two and six for a day which was a little extra than the regular worker on the farm. His pay rate was at that time ten shillings per week or two shillings per day, for odd times. The working day was 7 am to 5 pm and the owner of the engine had to arrive at 6 am in order to get the fire alight to get sufficient steam to start work by 7 am. I know that my dad has walked miles to do this and I have done so myself too. I have carried out all these jobs concerned, especially the untying of the straw bands around the sheaves of corn to supply the machine feeder.

My dad died from sunstroke at the age of 60 when we were doing some threshing at Kirby Farm during August, rather an unusual time for this work. His mate could not come, so he insisted on doing all the threshing machine feeding, leaving me to look after the engine and machine. In this way, he was in a very hot sun all day and it affected his neck. He died a fortnight later and after that I took over the threshing business for a time. It was 1904. You had to be at the spot for work by 6 o’clock in order to get the engine fire alight, to provide sufficient strength of steam to start it working for 7 o’clock which was the start of the workday. 7 am to 5 pm, half an hour for lunch, one hour dinner. Oh, and it was the rule for the farmer to provide food for the day – breakfast, dinner or tea or pay out two shillings and sixpence per day to the engine driver and mate, which they did.

The farmers then were not very well off, and quite often were unable to pay for this work at the time it was done. I believe the rate was two shillings and sixpence per hour of threshing time. I have known my dad having to accept corn or even a pig as payment and have done so myself too. As we both kept fowls and pigs for slaughter, that was one way of payment and so were able to cope with those problems, and a relief to the farmer.

Now regarding corn etc, there were garden allotments at Upper Tysoe, 86 originally and about 30 at Middle Tysoe. These were situated next to the village school which site is now included in the school grounds. The other sites were for corn growing as most rural men kept their own pigs, fowls and rabbits for the provision of meat for their homes. These sites were Longround, Winsway, Portway, Bridge Furlong and Promised Land. These were mostly set in two-acre plots. Dad had a piece of ground in the Longround. Wheat was grown to be ground into flour for their family and barley and beans for animals. Every effort was made to provide food without having to spend money which was very scarce. Then every household used to make its own bread, cake etc once or twice per week from their own flour mixed with ‘barm’ as it was then. It is yeast today.

So in my school days I have been in the harvest field with my mother and sister and brother gleaning or leasing odd corn after the farmers had carried the sheaves away and were able to collect sufficient corn which, after being ground at one of the old windmills, could supply us with sufficient flour to keep us supplied for use throughout the winter. Those were our summer holidays. This was in addition to helping Dad cut the corn.

Also, Dad used to collect mushrooms in their season, and I have had to rise at 3 am to go with him to help gather and return them, so that they could be sent on to Stratford or to Banbury to be sold. They then went by horse-drawn carrier to these spots?? I well remember following my dad down the Lower Tysoe Road while still dark and hearing the old church clock chime half-past three. On my return, I settled down on our old sofa to get caught up on my lack of sleep while Dad went on to work.

Well my dad, when the threshing season was over, used to gang up with two or three men for hay or grass cutting with scythes for different farmers. They would take on six or up to ten acres to mow, and would often start work at 5 or 6 in the morning, have one and a half hours for dinner time, then carry on until 9 at night. That was a good mowing day. Usually the farmer allowed them one gallon of cider per day, homemade and carried in a one gallon small barrel – and it got used too!

We have had to help Dad in the harvest fields. He would take on six to ten acres to be cut with the sickle or fagging hook and we had to help with the cutting and the tying. There was one episode which I can still show a record of. We were using sickles, as we all had one each. We had been told to put them on our left shoulder when laying out the bands, which we had to make. And I had put mine on my right shoulder. It slipped off and settled on my right wrist, made a nasty cut which was so open that we thought a piece had been cut out and my sister and brother were searching for it when Dad was informed. He sent me home after tying it up, and I had it bound up by the village nurse. This incident occurred in the field below Old Lodge. I went back to work the following day but was not quite so fit and I still carry the scar.

When Dad was mowing I had to take him his dinner from home if he was a distance away, during my dinner time from school and I have gone as far as the fields near to Hardwick Cottage – far end of Lower Road. In order to get back in time for school I often had to run both ways. However, I was the fastest runner in my age group while at school and it kept me fit. Also, while at school, I was able to jump as high as my top jacket button, just below my chin so plenty of practice.

Us children also had to go to Dad’s allotment on the Longround where he used to grow peas and potatoes to sell. When peas were in season, we children used to go there to gather them before school time. Approximately 6 am to 8 am was our working time, allowing us time to return for breakfast, so we were ready for school by 9 am. All exercise – sometimes with the old three wheeled basket frame, sometimes a wheelbarrow, and on our way we collected horse manure left on the road and I have known my mother go on this journey in the old pattens – a wooden flat sold, set up on an oval shaped iron ring about two inches high, with leather buckles. The roads then were very poor, just made up with hand-broken stones and only levelled by the horses and carts using them. In wet weather they were very, very dirty.

We kept pigs, rabbits and poultry and these had to be fed and attended to. Then on Saturdays we had to hand clean knives, forks, spoons, clean and polish all boots and shoes for outdoors.

I did very well at school under Mr Dodge, Schoolmaster. I have often been called up from 4th Standard to 6th, to tell them there the answer to their sums or work which they had failed in. My sister, Nell, went on as a teacher, and Mr Dodge wanted me to carry on as a student teacher too. However, my parents could not afford it, so I had to move.

And while I was at school, I was the fastest runner in my age group and one of the best jumpers too. I could always clear a high jump up to my top button, just below my chin. Not too bad on long jumps either.

Now at one time in my schooldays, I made an attempt to fly. Dad had a trap umbrella, quite large. One day, during his absence, I took it up on to the churchyard wall. There was a strong wind at the time. I opened it and jumped off the wall. By so doing, I went quite a long way towards the old middle path – something to boast about.

Then when I was about 11 years old, I had a bad attack of tooth ache. I could not sleep at night and it went on for a fortnight or so and I was pretty miserable. I had heard a story about the old stone monument in the centre of the churchyard – if one was there at midnight and went round the surrounding steps as the church clock was striking 12 and shouted, “Damn the Devil”, he would appear. Without my parents’ knowledge, I tried it out one night. I got there, did the round and shouted. The Devil did not appear but my toothache stopped and did not occur again. I boasted of this to my school friends but did not hear of another case.

Now about the church – my mother was the cleaner there and my sister and I had to help. Sometimes, if Mother was too busy, we had to do the whole of the work. One Saturday afternoon a very severe thunderstorm was raging. I went from the chancel steps towards the belfry to get a broom from the cupboard where it was stored. As I reached the curtains, there was a crash and a flash which nearly blinded me. Lightning had struck the tower and it came down the wire rope in the corner cupboard, unsettled the weights at the foot of the wire, connected with the clock. Then it deflected to the very strong iron hinges of an old door standing nearby. It bent those hinges before earthing onto the floor. I was approaching the cabinet where it descended. Had I have been at the cupboard I might not have been writing this now. A lucky escape for me. Anyhow, this stroke destroyed one of the old carved pinnacles on the tower and damaged the clock. The pinnacle was later replaced and the following Sunday, the vicar gave thanks for the preservation of the tower and for my eyesight too. I had about a fortnight before my eyesight became normal, after treatment by our doctor.

At this time, I was a choir boy and had to attend service on Sundays two or three times. I used to be on call for the blowing of the organ. Sometimes, I used the lever for the blowing of the organ, and there were times during the week when as I was close by that I was called upon to do so, for people who went in for organ practice. This brought me a little pocket money – two or three pence per time. We had very little pocket money from our parents. Sometimes a penny or two but got some for running errands etc if we were lucky. In those times we could get a quarter of a pound of sweets for two pence or a pound of sugar. Unknown to my parents, I bought some brown sugar to eat. We then slept up in the attic bedroom, my brother and I. Well, I took some string, a fairly long cane and an old mug. By using the cane, the string and the mug, I was able to bring soft water up to our window out of the barrel below, and we had a few sweet drinks. This was carried out unknown to our parents – naughty boys.

I used to help Neville Styles or his brother Jacob to wind up the clock in the tower, and I have been up there when the bells were started. One could then feel the tower sway from side to side but was not alarmed. I once went through the bell tower with Neville when they were in full swing, creeping along the beams to get back to the stairs, and we got a real choke from the head bellringer, John Wather, when we reached the vestry floor. A dangerous thing to do.

Now in those times our chief play games were to go foxhunting or play Robin Hood games. One boy set off as a fox to trace a way through any of the surrounding fields. Then after allowing time for a start, the others followed, if possible. The Robin Hood game was all carried out with homemade bows and arrows, and could be quite exciting. The target for shooting to kill was usually a thick stick set up in the ground or a piece of paper tied to a stake or a tree. This game was usually carried out in the old Herberts Close.

We would try tree climbing too. I remember a tall elm tree I once climbed in the corner of the field next to Herberts Close and near to the brook where I was able to look down on the top of the church tower. It was about six feet higher – just one way to get a rise. By the way, the Old Rectory was where J West now occupies and the farm, Rectory Farm. I remember one of our schoolteachers who came from Oxhill, Arthur Rouse, climbing up the iron railings to get on the saddle of his penny farthing bicycle.

My brother, Ernest, the youngest of our family was always spoilt and we had to look after him. I once took him to the old clay pit in the brook below school to play. He got dirty. I didn’t and on our return Dad was there waiting for us near the door. There was a soft water pan opposite. He was going to punish us. I sent Ern first, he got kicked on his bottom. It lifted him up and he finished in the soft water pan. During the confusion, I nipped by and thereby escaped my portion. A few days later, Ern and I were clearing some bean sticks in the shed, he got behind me with a stick and hit me on top of my head. I was completely knocked out and lay on the floor until Mother revived me. So he got his revenge.

Well in those times, we kept pigs, fowls and rabbits. All were kept for food for the home and as children we had to attend to them. On Saturdays, we had to clean all the boots and Mother’s shoes, the cutlery etc. Our mother then used to go out as a midwife in the village and at times my sister and I had to attend to the housework and cooking. Ernest was always excused. When he grew older, he went to finish schooling at Birmingham. He stayed with brother George for a time, then he later took a job with Mr Savory (?) from Sunrising House, in London where he stayed until retirement – clerical work. During the start of that, it was after Dad’s death, Mother and I had to help him pay for his lodgings as he was earning very little. Later he became head clerk to their company, so finished up quite well.

Working in Birmingham

Now I will leave the school days and go to Birmingham. I left while still 13 years in age and went to help my eldest brother, John (your Uncle Jack), with his bakery business. He took me there to get me a start. He gave me the odd two pence from each shillingsworth of cakes that I sold as my wage and, of course, I had to be kept by him too. This went on for a time, a year or two, until he went bankrupt and gave up his shop and business. I used to look after two horses he kept for delivery of bread and go out delivering daily with the cart or van. Always a full-time occupation.

Afterwards, I took a job as delivery boy at a big store. There I had to assist with the stores and deliver orders within a radius of two miles to various customers. My delivery truck was again an old three-wheeled basket carriage. Pay rates were then five or six shillings per week at my age. I collected a few small tips to help. This went on for a time, when I transferred to another company at Stirchley doing much the same duties for a little more cash. It was then five to six shillings per week. I was living at Cotteridge in the first place.

Then later, when that closed down, I got a job in a copper factory at Selly Oak. It was better pay but longer hours. This meant that I had to walk approximately three miles to get to work at 6 am, starting at 5.15 am. I found that the quickest route was along the canal path which was used by horses and donkeys for towing boats on the canal. One had to take care on dark mornings and evenings. During one dark morning I crashed into a donkey and ended up in the edge of the canal. I got soaked up to my seat. However, I scrambled out and ran to work. It was quite warm in the works and I gradually dried out.

One morning I arrived at the doors just as they were being closed. I got one foot inside but the doorman pushed me out. That meant a quarter of time lost as the next opening time was 9 am. While I was there my work was to unroll large rolls of metal as it entered a large rolling machine, to be thinned down for the cutting out of wire. This meant that I had to keep my weight on it as it went into the roller so I was always bent down. I had lots of backache pain and when mealtime arrived, I scarcely knew how to stand upright. I stuck it out for a time as it was good pay. I was the youngest one to tackle this job at 15, as they had not employed anyone under 18 before. Strangely enough, Willoughby Wells from Tysoe came round one day. Unknown to me he was there serving an apprenticeship – now dead in cemetery.

Back to Tysoe

After a time there – at the factory – not at above, I decided that at 15 I was just right for the Royal Navy. I went for a test in Birmingham and passed, except that my parents had to sign the form and I had to have my tonsils removed first. I went back to Tysoe for this purpose, but my parents would not sign. I had an old bicycle now and cycled over to Horton Hospital, Banbury to have my tonsils removed. This operation was carried out by hand, no injection or anything, except a wedge to help keep my mouth open. Afterwards, I stayed there for one hour to rest, had a cup of tea and cycled back to Tysoe. I was a little sore for a couple of days but I recovered.

My parents did not change their view, so I started off with the threshing business again, and any odd jobs I could find. My dad wanted to train me I expect so that I might keep up the family business. So I got work where I could from the farmers during winter months in this business, then took on jobs – corn hoeing, haymaking, corn cutting through the summer months and by so doing managed to get enough income to pay my way.

I was growing up a little now and I ganged up with a few friends and between us we went in for athletics – running, jumping etc. We got the use of the first stable at Rectory Farm on left, as you enter Mr West’s stable yard. We took over the stable from Fred Jeffs who specialised in cart horse transporting. He lived where Mrs Hawes does now. It had some iron rings made at J (?) Smiths, and a parallel bar. We got an old lantern for light on dark nights. I soon discovered that I could just reach the bar or rings from tiptoe, go over or under bar, or with rings and return to normal. Some others could do so but not everyone. We practised high jumping and long jumps outside where the cow yard now is. I could run the one mile but much faster in the half or quarter and usually came up amongst the first three. Then, between us, we bought boxing gloves and went in for boxing. I was pretty good at that too. We went in for jumping in the orchard, as it was then, now a cattle yard. And one Tysoe Flower Show, I managed to do a six foot three inches high jump which was at that time a Tysoe record. I could also do quite a good long jump – twelve feet and beyond, and standing high jump with side swing, four feet or so. So a little jumper. I could run a mile, half mile and quarter mile, usually up amongst the first three. I played football at odd times but not regularly at this stage and I still had to help with the gardening jobs. I also got interested in tennis. At that time there was a tennis court in Heritage Field, close to the Green. I was not too interested in girls then but later I went to Miss Turner’s, the village nurse, and there I met the one who is now your granny.

Anyhow later, I went for a day’s work at the village nursery, on the Green, to handsaw logs off, ready for fire use. I met the housemaid and she wanted to learn to ride a bicycle. This is where I started to run after my wife. I offered and afterwards ran a few miles at different times, up and down the old Oxhill Road teaching her and that is where we started keeping dates.

By the way, the nurse there was installed in the house where Mrs Clifton now lives at the expense of the Fifth Earl Compton. There were no cars then. He used to be driven around by a groom in a carriage with a pair of horses when in residence at Compton Wynyates. He also used to provide a piece of beef at Christmas for all the elderly people of Tysoe in addition to other charities in our village and Winderton too, wherever he had his property. All of Tysoe then belonged to him and there were quite a few men employed by him too, and a lot of people used to wait in Tysoe to see him arrive at the church which he regularly did when in residence.

Soon after this I got a job at Coventry in a motoring factory. I stayed with Aunt Polly there as her husband was employed at the same place but I cycled to and from there weekends to be home at Tysoe. Anyhow, I did not stay at that job very long, coming back to Tysoe to live and work as before.

Well I managed to find enough work on farms etc to keep me going. I have been out on a farm with horses at ploughing jobs occasionally, not so very interesting wandering round and round in the open fields all day. Mainly, the ploughing hours were 7 am until 3 pm with a lunch break and a dinner too. The threshing was still in action at the winter period and we found something to do in the other times. My dad was a fairly clever mechanic as things then were and I occasionally had to help in different repairs.

I have done haymaking on the Burland and Kirby farms, Middletons and Gardners. I once took over that field which Gerald Butcher (?) now owns and cut the whole crop of wheat by hand. Just another job – piece work.

One more outstanding event was the annual children’s day’s holiday at Compton Wynyates. Farmers used to take them there and return them in wagons, all horse drawn. They had games and prizes and a good tea indoors and each had a bag of sweets and an orange – very special to us. In my first lorry, 1920, I once had to return children to Tysoe as it came on very wet. They thought it was so wonderful. Luckily, the lorry had a cover sheet top.

After some time, the village nurse was either discharged or she left Tysoe and returned to London, taking her housemaid with her. In order to keep in touch, I cycled to London and back to keep in contact.

A funny little episode occurred. My brother, (your Uncle) Ern and his then girlfriend were fond of boating. We were all together one weekend. Aunt Elsie – as she became later – had been making up some red cushions for their boat. We all went out one Saturday afternoon for a boat trip on the Thames. Ern did the rowing, I did the steering, and we went quite a distance in quite nice sunshine. After our snack and tea on the riverbank, it came on to rain and we got it too. We got ready to return. I offered to use the spare pair of oars and your Gran was to steer. She tried. We wobbled all over the Thames while returning and when we reached our destination the girls started off quite quickly while we put the boat away. As we later were about to catch up on them, we saw on their rear two large round patterns of red from the cushions they had sat on. We laughed but they were embarrassed and annoyed and on reaching our lodgings they refused us our goodnight kiss. Anyhow, this episode passed by.

A little later, Lily returned to Tysoe and in time got a job at Moseley, Birmingham as a housemaid. I went with her when she left Tysoe, by train from Stratford station. Afterwards, I cycled to and fro from Tysoe, to keep together. She had a half-day off weekly and a full day monthly. So I spent quite a lot of time on the old bike with one gas lamp, one oil lamp. Once, I cycled there with a boil on my seat. I could not sit on the saddle and had to just get the balance on my legs. That burst while I was in Brum and I had to visit toilets to get mopped up but the return journey was easier.

I once took her bicycle with me for her to keep and use. There were very few other means of transport. A long way to push one and ride another. Mostly, it took me two and a half hours. I once rode there through four inches of snow using tracks made by horses and carts. No salt on roads then. One just had to make the best one could. However, I have no regrets. Although, on returning, I frequently had to be at the engine to light up by six if we were threshing, my time to leave Moseley was 10.30 at night, so early morning rise. Afterwards I used to find that the hill this side of Stratford was the worst part for me on these double journeys. However, I got by and after a time we married (in 1912).

Married Life

Well, after our marriage things did not go so well financially. My father had now passed away [James Lomas died August 24 1908, per memorial in Tysoe churchyard]. He had previously sold the steam engine to his old mate, Sam Reason, to pay off some of his debts. So I only had the threshing machine and my mother to keep. Mother and I lived in the old cottage where George Hancox died. Later Mother went into the old single roomed one on the corner. My wife and I went into the one next to the old workshop that was, so we were all saddled in Saddledon Street. Add one more, our son Jim was born there in August 1913. Before this came along, I had attending working classes in the evenings to learn carpentry. However, our marriage went off alright but not enough income. I have known the time when we had not got one penny to spend although I tried hard enough to get some.

So I decided that the old threshing machine must be sold, and this was done. George Canning bought it, father to Alwyn and Conway, then living on the farm where Mr Cox now lives (not the bungalow). I started working for him, he also had the farm up Banbury Road, where Edward Parker now lives. He bought and trained riding horses so I have helped with their training. He also went in for milking cows, about six or so which I often milked by hand. And he also ran a business of collecting from various farmers butter and eggs to supply by horse and trap to Leamington shops. I have taken them betimes, as well as doing the collecting, mainly by bicycle.

I once went with him to just outside Leamington to fetch an untrained young horse with just a blanket to sit on and a bridle. I rode this horse all the way back to Tysoe. I rode along fairly well to Kineton. Then it insisted on turning back and was very awkward. I had to let it go back a little distance and then make a turn-about. When approaching Tysoe on the Lower Road, I had to dismount and walk because my seat was becoming sore and it did trouble me for about three weeks. That same night, George went out on it, fell off and had a broken leg, so then he depended on me for a few weeks to run his business to Leamington by horse and trap, and look after the cows etc. Well our first son, Jim was born about this time and went to Leamington with his parents several times. There were several shops which we served at that time.

I was not keen on this work and after a time, I answered an advert in some place and I got a job out at Snitterfield. A farmer who had a threshing business and a steam traction engine. I soon learned how to drive the engine and took over his threshing business, working on the farm occasionally. And I stayed there for a time. Quite a good wage at that time.

Your Granny and I had been living in Saddledon Street in the old cottage next to the old workshop and after a time we moved over to Snitterfield but did not care too much for the place. We had to walk into Stratford for any shopping – no bus or transport. Quite a walk with baby Jim. So later my brother, George, got me a job out at Birmingham, at a large hardware store where he was then chauffeur to the head of the firm. My job was to pack up the hardware into wooden boxes or barrels for delivery for both home and abroad. I also looked after the lifts they had in use, two of them hand operated. I used to go in an hour early to do this job, extra payment, and lived with sister Polly for a time.

Wartime Experiences

Well, the 1914-18 war had now started and, after a time, I found that I would be compelled to join up. I decided to volunteer, so went and passed into the Royal Ordnance Corps, supposedly as a steam traction driver. This was September 1915. In this way, I got a little extra pay, the same rate as an ordinary army corporal but I never once had the opportunity to drive a steam engine. I was allowed four shillings and sixpence per week which I could have had for myself but I gave over the one and six as an extra to my wife. As I was neither a drinker or smoker, I did not need a great deal. We put our furniture in store, so a little had to paid on that. I was sent to London for training and after ten days was sent over to Le Havre in France. I could have had twelve hours leave but to get to and from Tysoe, where my wife and son were gone, it was too much so I stayed on.

We went by train to Dover from London and the sea was rough on arrival. After three attempts we were on our way in an old paddle steamer, ordered to stay down below deck with all our kit and everyone became seasick. Not a very nice voyage. We got over and we went into camp not far from the docks, six or eight in each tent with very little comfort.

Our job there turned out to be assisting to unload ships of material (picks, shovels, rifles etc) for the armies, putting them in store and preparing the for despatch up the fighting lines. I never once had the chance to drive an engine during my service in the forces.

We did not have a very large wage but were fed in some way or other. I can see us when up in the front line, having our day’s food brought to us as soon as daylight was in view, and some of the hungry ones would eat the lot straight away. I never did this but I kept a portion for later on and caused jealousy to some who had gobbled it off straight away when seen eating it. A lot of the food then was very hard, dry biscuits, corned beef and sometimes horseflesh – all tinned food. The occasional loaf of bread usually issued to a corporal to divide into a portion each to his group. I was in charge of our platoon’s bomb squad, six or eight men, so I often had this responsibility but I always cut it up into equal portions and gave them their choice first, myself last. While this little game was going on, the tin of meat was issued to a greater number and it often occurred that you got a portion of one but not the other which caused a few naughty words to be used.

While in France, I learned to speak a few French words and I soon took advantage to go to some French cottage and ask for bread of which we were always short. Officially we were not allowed to do this so it had to be on the quiet, or at night. I once went to an old cottage near our camp, at night, with two tins of corned beef which came out of our daily issue, and which the French peasants would always willingly exchange bread for. Two steps led up to the door and just as I was approaching the door, it opened. I must not be seen, so crouched down by steps. A man appeared, did not see me and sprayed me with his own water which he had come out to do – rather uncomfortable but, on his return I got inside. Two women and he laughed as I showed them my wet self but I got away with three loaves of French bread for my exchange and my mates were delighted.

Another time, I approached a bread delivery van which was surrounded with French wives. Just as I was going to be served, I saw one of the officers approaching. He had not seen me but the ladies knew the rules and they immediately surrounded me as I crouched down and when he had passed, gave me some of the bread and some cakes too and quite a few smiles. In this way, I got known in my platoon as the Bread Boy. When we were really encamped we got sufficient food but when on the move, it was very dodgy.

On our camp, I once became the runner to the Camp Officer, having to accompany him and run any errands required. Well, once there came a time when one officer was being transferred somewhere. At that time, officers were allowed to get their clothes out and washed by French women. But not us – we had to wash our own. Anyhow, this officer’s clothes had to be fetched in before his departure. I went with the Camp Officer about half a mile away to some old country cottages for this purpose – found them packed away by the washerwomen in an old laundry basket, too much for me to carry. One of the women offered to help, so we started off. After a time, she started talking in French which I could not understand, so I kept walking. Then she set her end of the basket down and squatted on the grass to relieve herself. I had to wait and just as we were about to start again our troops came marching out of the camp gates on their way to the docks, just in time to view what was happening. They started to grin and on their return at night I had quite a few nasty suggestions thrown at me.

However, I survived and knew that the French were not too clean in their habits. I soon discovered that it was nothing to a French woman to relieve herself at the roadside in those days. I have even seen them enter a gents’ place with their husbands or men friends, still holding his arm while he relieved himself without any embarrassment. These places were very open too. One could see the top part of the man from outside. Also they thought nothing of emptying their rubbish in the street gutters and outside their homes. I expect times have now changed there, this was mainly out in the open countryside where we were.

Another little episode happened while I was Camp Officer’s runner. I had to do various jobs and report anything that needed attention. We were in tents, six or eight together. The only place we had for our relief was a six-foot trench, dug out at the back of our camp with a spade set up for our use. Along one side of it a pole was set up, surrounded with sheeting and daily filled in with soil, until it reached near ground level. It could be used by six men at a time and was not emptied for a week or so. Then a fresh one was opened up. One night, one of our tent mates had to pay a visit. An enemy plane passed over and a bomb dropped and exploded close by us. The Germans were trying to bomb the docks. He was so frightened, he lost his balance and fell in the trench. After a struggle, he came back smothered all over in refuse. He called from outside and we got a really dirty and smelly view. I had to go to Headquarters to report this episode, go back to lead him to the officers’ quarters for a sprinkle bath – this was the only bath on our camp – get him some more clothes to wear as his were ruined, so that he was back for normal work.

We were each issued with a rifle, to be ready for use if required, a spare shirt and socks and a six-foot by three-foot rubber sheet and leather jerkin, a flask for water and an emergency pack of biscuits and a tin of corned beef, a small pick and shovel strapped to our belts, and have actually had to excavate a six-foot trench with those. Hard work.

While at this camp I caught an attack of scarlet fever. There were two more and we were sent to an isolation camp near to a hospital. One of us three had returned from the front line and was rather badly wounded in his leg. We were there attended by Australian doctors and nurses. It came on to snow. They had never seen any and were delighted to have a little snowball game with us. Then, this fellow with the bad leg was in a poor condition, pierced right through near the main artery and, as we were separated in huts away from the hospital, I was interested what to do if anything occurred. They were a bit alarmed in case he started to bleed and instructed me what to do if it came off. It did one night and I heard him shout ‘Frank’. He knew me and, on lighting up our candle, I saw him with blood shooting from his wound a yard or so up in the air. I followed my instructions, lifted the foot of his bed, set it on his cabinet and applied a bandage. I give him water to drink and then rang the emergency bell for the staff. A doctor and nurse quickly arrived and he was attended. Later, I was complimented and told that I had saved his life.

Well after a time us three were transported to the docks and we were returned to England and by train to Nottingham Hospital. But we were kept away from others as we travelled. Through the staff there, I managed to find some lodgings for Mum and baby Elsie, our only daughter. On my release from hospital, after a short time on leave in Tysoe, I had to report back to York and was then sent on to Selby in Yorkshire where I joined up with about 30 AOC men. They were running a camp outfit job there, with outsiders helping, making up tents and all equipment. I got a job there as assistant cook. I had to collect our food daily from the railway station, sent on from York and then assist with the cooking but quite enjoyed it. There was only one there and he would leave me there to do the whole of it, but I got on well., even better than he did, and once when he had had ten days’ leave, the boys put in a request for me to stay on and turn him out but it did not work out.

While there, during wintertime, I learned to skate, as we were surrounded with ice. Some adjoining fields were all completely covered, so actually miles of skating. The water was overflow from the River Ouse. And I once got permission for my wife and baby Elsie to stay for a fortnight in the springtime. A very nice time for us all as I found a very friendly lodging place for them.

Afterwards, as the Army was short of recruits, all of us AOCs were transferred, if fit. So I entered another lot, the Royal Essex Regiment and that meant another lot of training before being sent back to France to fight. Some of the episodes I have already stated occurred after this transfer.

Anyhow, after a time out there, and while I was away on a course, our company got wiped out. My wife was informed of my death but luckily she received a letter from myself at the same time, stating where I was and why, so that eased the situation. Lucky to be away, as they were nearly all killed. On returning to headquarters, we were not long before we were transferred to the Royal Essex Regiment and that is the one I finished in. I was raised to rank of corporal and put in charge of the bombing squad. One of our experiences was, we went into the front line to take over from the guards who had captured this position. We were under fire quite often and as we were approaching the line we saw quite a few dead lying around and there were horses too. A few Germans were being brought back and we had to take them over, to go back to our headquarters, a mile or so in the rear, so we were very busy.

Our final advance to the front was through a thick wood where our little gang caught five Germans in a deep hollow. We threw in a bomb, wounded some and captured them. Strangely, one of these spoke English. He had been working in England, returned to Germany and had to join their army. He was quite good and gave our officer quite a lot of useful information as he then thought they had lost. However, we went on and relieved the guards at about 200 yards from the Germans. They had to wait until dark to creep back and we were without food all next day, having to use our emergency rations. I remember seeing one of ours throw his rations out the previous day. He wetted on them – said they were N.B.G. but the following day he gathered them up to eat, as he was desperately hungry. Officially, we were not allowed these emergency rations except under officers’ orders.

While in this spot, I crept over the top of the trench with a mate. We got right up to the German line during darkness. He got round a hidden marksman and killed him. Afterwards, he was awarded the VC but I got nothing. While there we saw far away on our right, masses of Germans who had made an advance and the same night we were ordered back to our headquarters. We were only allowed out in fives and had to find our own way several miles to our rear. Some did not make it, but I, with four others, did and we were glad to find some food and water on arrival. This was one time the Germans advanced on us.

Well this fighting went on and I had all sorts of experiences, and several lucky escapes. I was once sent with my bomb squad towards the enemy line. We got close enough to hear them talking, and I ordered our bombs to be thrown at the Germans. We must have killed several of them. We started back and a few shots were fired at us. One of our squad made a mistake and we had an explosion amongst us. The chap next to me was badly injured. We managed to get him back to our line but came under fire by the time we reached it, approximately 300 yards.

The next day, I crept into some old farm buildings to get some water which we desperately needed. I found a tap and, as I was approaching it, a German soldier appeared with a can for the same reason. He had a rifle. I showed him my empty hands and pointed to the tap. He signalled me to get some water and laid his rifle down. He then got some for himself. Together we looked around, found some eggs – hens’ eggs – which we divided, then parted and this went on between us without any fighting for a week, when we were withdrawn. Him and I shook hands when we met each day but could not talk. All this was unknown to our officers and although we were not far apart there were no further attacks at this spot.

In any case, I would not have known much about it as in my duty, I was helping the officer in charge of distributing our food in the early mornings. He had a gallon jar of rum which was sometimes issued. I was ordered to distribute this rum to our platoon. I did but I filled my own water bottle and later had a good drink. I became drunk and had to be taken to the officers’ quarters to sleep it off. I was never a drinker but this was an exception and I got away with it. I was not punished for it. Although we were issued with fags/cigarettes, I never smoked but let my mates have mine for a few coppers. You will see that as an athlete, I left smoking out of my life and in my younger days no sort of drinks had any attraction.

I had one wound during the 1914-18 War, a bad blow on my left leg with a piece of shrapnel. I was sent back to hospital to be stitched up and treated. The Americans had just taken part in the War and this hospital was staffed by them. They were not too good and understaffed. I took part by attending to bandages, looking after equipment and even went so far as attending some patients when the nurse was too busy. She, the nurse, did not want to lose my service and actually (with my consent) cut off my stitches so that I could remain a longer time in order to help her. I also gave some blood for the same reason (better than fighting).

Once we were taken out of the firing lines to a small, deserted town – I don’t know the name. We were put in cellars under shops during the night I crept up the stairs to the stores above and, strangely enough, found some bottles of wine. I took three, returned to my mates and our company officer walked in while they were drinking it. He asked where it had come from and I was ordered to get some for him which he took away to the officers’ quarters. I was ordered to say nothing and to stay below the floor as first ordered. Strangely enough, while there I was on duty above during certain hours and walking down the road one day saw Phil Walker. He had brought a message to our officer from his, a distance away. We had to stay there ten days. All the place had been deserted. I did not see Phil again but apparently, he was then officer’s runner.

I’ll carry on now towards the end of the war. We were once withdrawn from up front duty and had not had any change of clothing for five weeks. We found an old iron in a broken-down building and some tubs too. We lighted up a fire and washed. I did the ironing of shirts and trousers – they were then full of lice and the iron frizzled them as it was used. There were a lot of lice about then with almost everyone and it was almost impossible to get rid of them. Once, a pal of mine took off an old scarf he had been wearing for some time and killed 60 lice from it. No wonder I have now got skin trouble. Soldiers today would not try to work under the conditions we had to.

I can remember the first planes that came into action, also the first tanks that came into life. Horses were used then for any sort of transport – wagons, large guns etc. Hundreds were killed. We had to walk everywhere and on some occasions as much as 30 miles which was a long distance to carry all our equipment. There was one time when we were going to take over a front-line position. We were all issued with two sandbags and four strings. After a start, we got into a muddy section and had to stop, put the sandbags round our legs and tie them on. We then knew why they were issued to us. We were in a valley and the sludge and mud came up to our thighs as we went on. There were two of our platoon. One was a leading officer who got completely stuck in the mud. This was during the night we were moving. The had to stop until daylight before they were released – what an experience. Later some wooden framework was put down in those trenches and as we returned to support lines after ten days in front, I nearly copped out. A German shell went into the side of the trench just about one foot in front of me but luckily it did not explode.

During our advances and retirings we stayed in all sorts of positions. Once we were returning and night was approaching and we pulled up near an old farm. Some of our lot got placed inside the barns and outbuildings but I, along with others, had to stay outside. Three of us got together on the outside wall, laid out our rubber sheets and blankets together, and so slept. In the early hours of the morning, we woke to find three inches of snow on top of us. Another experience. But we were there issued with a nice warm breakfast before moving on again. Another time when we used a farm barn, we had a lovely lot of straw to lay on but during the night, mice woke us up by running all over us, bodies and faces – not so nice to know.

I kept on going with the others until one night we were led towards enemy lines and settled down in ditches around an orchard, ready for an advance in the morning. Around 3 am a corporal appeared and handed on a paper with my name and two others of our platoon to return to headquarters, some miles in the rear. We had been serving abroad over 12 months and were granted a holiday back home. We had to report back to HQ to get our papers etc and this was several miles behind where we were, pass through the second line and the third to reach HQ.

As we were nearing the third support line, the Germans opened fire and shells dropped around, fairly close to us. I had one shell explode within ten feet of myself and, as I was entering a trench, another one went into the wall three feet ahead but did not explode. Lucky me! This was the only time during my service that I felt afraid – thinking of coming back to England etc but we dodged through. After spending one night at HQ down in a cellar attached to an old farmhouse, we started off towards our destination, Le Havre. At that time, I had a pocket watch which showed the north, south, east and west on its face. We were in strange surroundings, had 40 miles to travel, were not allowed any lifts by the horse-drawn vehicles on the roads. The watch was a great help. We had to spend one night in a broken-down French railway wagon but got to our spot a day in front of the stated date for departure. I managed to get us on a boat to cross over so we were a day in front. On to Dover, then train to London. Then I went on to Banbury.

I got talking to a man on the train and he said that he might get me a lift in a horse and trap to Shenington. We walked from the station – Banbury to Warwick Road, near where the old hospital is. I was invited into his house, 10.30 at night. He went out to find the horse and trap and his wife insisted that I have his evening cooked meal. She said she could find him some more. Anyhow, he returned to state the transport was gone. They offered me a bed but I decided to walk home. I had my rifle and most of my equipment with me to carry and I started. It was wintertime and came on to snow. By the time I reached the Wroxton fields there was two or three inches of snow. I found my heavy army boots very slippery so took them off, and added my spare socks and so continued to walk in them. I came to Old Lodge and down the fields to Peacock Lane and got to The Green in the early hours of the morning. So, back home – Tysoe. My wife was living with her granny at that time. I made a noise and was welcomed indoors.

Returning to Civilian Life

During my ten-day holiday, the Armistice was agreed on, so I decided I would take two days extra. And after returning to France, I was stripped as a corporal but it did not affect my pay. I was demobilised the following February, 1919 and, after a holiday, had to return to my work in Birmingham. On dismissal from the forces, we were all given a suit – civilian, a fortnight’s pay, a small sum of money as compensation in PO Bank, allowed our heavy army boots and we got our medals.

After a few days at Tysoe, I went back to my job in Birmingham and we arranged to share a home with Mum’s cousin, near to Aston Villa which went off very well for a time. But I had to travel by bus into town and it became too expensive. I nearly entered the City Fire Service but there was no married quarters so, about Autumn time, we decided to return to Tysoe and so got into an older cottage at Lower Tysoe, with no job to go to and no dole as I had left my job in Birmingham. We lived mainly on blackberries and apples.

Starting Work at Compton Wynyates

Uncle Fred lent us £2 and at the end of six weeks with only an odd job, I got employed at Sunrising House which was being altered. I walked up and down daily through the fields and was employed as a builder’s labourer. Just a few days after starting there, I was notified that I could have dole by applying at Leamington as my six weeks period was passed. I ignored it. I kept going there until April 1920, when I had the opportunity to work at Compton Wynyates. I took this job although it took a little extra time for a smaller wage. I lost about 4/6 per week, but it promised to be a regular job so that is how it started during April 1920.

I learned to do all sorts of work, from 6 am to 5 pm and on Saturdays, half an hour for lunch, one hour for dinner. About 15 men were employed there. Mr Thomas Parish was the foreman. We were paid monthly and had to walk to Long Compton to fetch our wages. An agent lived there at that time. I learned the art of tree felling, preparing fencing materials by hand, doing fencing work and helping with building jobs. As I was one of the younger ones, I had to help with erecting scaffolding, getting sand from various sandpits on the Estate, and stones from the stonepits. Then, as I was a bit mechanical, I was taught to drive a Ford one tonne lorry, the first that came into our Tysoe district. The farmer agent, Frank Spencer of Winderton, was my first instructor but they were not fast then. The recommended maximum speed was 18 miles per hour. Solid tyres, covered front seat and no screen. Lovely when it was snowing! Later a plain glass screen was added. I had to go to Kineton Station to collect truckloads of coal for Compton House, also cart logs in for use, take bricks, sand, stones etc for building repairs; always busy. I have had to go to Castle Ashby too for materials, in addition to luggage to and from Banbury Station.

Then in 1921, an electrical plant was installed near Compton House to supply the house, the church and all surrounding buildings and I was put in control. I worked with the electricians while the House was fitted with wiring etc, so got some knowledge of electricity, and afterwards the maintenance of all was left in my care for 17 years, for which I was paid two shillings per week extra. Quite frequently, I had to work on electric plant on Saturday afternoons and all of Sundays when there was company in the House, in order to keep up with demand. However, I coped with everything and got through.

Then I got involved in doing little repairs in the House, fitting carpets, curtain rings, attending taps, bits of carpentry, plastering, decorating and roof repairs. Later, I got among the building jobs and at the finish there was no job on the Estate that I was unable to do. In addition to running the lorry I had a tractor to attend to and the saw bench where we sawed out/oak?rails for fencing etc, gate posts and other posts. Once I had a spell making field gates and could just accomplish two gates in one day. I did soldering jobs in connection with the electric wiring and all tools required had to be your own – none were provided by the Estate, so I got all sorts of tools which I bought out of my overtime money which was time and a quarter – nothing very high in those days. I will add a little more to my Compton work.

During the Second World War, I was shown how to do drainage and water supply and we had a gang or war prisoners under an officer who came and dug the drains needed. I connected and laid water supply pipes between Compton Windmill and Lower Compton, then on to Whatcote. Also, on to Lower Chelmscote and Hill Farm. Then from a supply near Winderton to Upper Chelmscote and to Middleton’s Farm at Lower Brailes, inserting drinking troughs where needed. I did a lot of drainage where needed too. Built in a few fire grates at Compton House and at Lower Compton too. Set posts and hung gates all around the Estate, as well as painting and decorating. So, without boasting, I was a very useful man at Compton. No job I could not do. I was never late starting to work and usually the first to rise and get started after lunch and dinner breaks. I also laid in water supply pipes to Downs Farm from springs on the hillside and a few water troughs too.

During my period of work at Compton, I had the pleasure of waiting on my mother in the Back Lane. After she reached 80 years of age she was unable to walk to Upper Tysoe which she did up to that age, for her Sunday dinner. I used to take it down, see that she had plenty of sticks for the fire and go to her garden etc. She moved into Front Street at 84 with Uncle Jack and died at 88. He came to live with her and even took her small old age pension. Then I had another job – my wife’s father was a diabetic. He lived down Smarts Lane with his son and had to have injections daily. No one else could do this job, so I used to call every morning on my way to work, twenty or quarter to seven for that job. He Iived until he was 80. So I always had some responsibility.

During my driving duties, I had to collect and return luggage to and from Castle Ashby, Banbury Station and I have even been as far as Southampton. I collected the first ladies wedding presents from Longleat to Castle Ashby amongst other duties. Then I was requested by the Marquis to help with the guiding duties and I managed to complete 28 years at this occupation and was very popular with the visitors.

Retirement

At the age of 70, I retired from the Estate work except for two days per week and on one occasion, I slipped on a ladder in Greenways yard and had a broken leg. I had to got to Warwick for treatment and broke all records there as I returned on two sticks in five weeks and three days. I was told that I would be unable to do gardening etc but I did not allow it to stop me but I knocked off all Estate work and just did the guiding job at Compton until August 1974. So a period of work for Compton Wynyates of 54 years. Anyhow, I get a small pension and a free home for my services and at 86 I am fairly healthy and happy.

I have been a very active man in many ways but I do find work a little more trying now – in 1976. I am now ageing a little. I can and do still drive a car and do some gardening. I still keep some bees which I first started in 1922 and of course a family of three children, six grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. I am very proud of my family too. They are all good workers, whatever they do, and are all willing to help Granny and myself, if needed. However, we manage to get through by sharing all housework etc and hope to keep on a little longer, as I am getting used to it. I was very self-confident and throughout my whole life my motto has been, ‘Be Prepared – Have Faith’ and I think I have lived up to it.

Addendum (1)

I will now go back to my return to Tysoe. I was a member of the Ancient Order of Foresters and after a while, I was offered the job of Secretary. This was the time when the National Health was run through the Friendly Societies. So you can imagine the work attached, issuing of sick certificates etc. via the doctor, then payment of such sick pay. And the rules were pretty strict. No leaving home before 8 o’clock or after 5 o’clock, no work to be carried out at all while on the list of sickness – quite tight. However, I coped with that for 15 years. It was a little more on income which helped a bit. I have frequently done booking until midnight in order to keep in order but was pretty good at it.

Then I fancied a motorbike and got one for a few pounds. A belt driven affair which could slip in wet weather, two speed only and not too fast but then it was wonderful. After a time, I changed to motorbike and sidecar – Royal Enfield which I kept for some time then sold it for four pounds and ten shillings so that I could get a better one. This was a twin cylinder Matchless, costing twelve pounds but it was a really good machine, a two-seater sidecar and very strong and we used that for all sorts of purposes starting with a seaside holiday with it in 1921, camping and continued to do so throughout the years. We were the only ones amongst the working class to do this in Tysoe. I had a tent and all equipment for this purpose and Tony still has some of it. I had to work to keep up with demands and used to do odd jobs around, and so managed to keep going. Finally, I sold it and had an old Ford 8, through Uncle Gerald. First time I used it we went to West Bay with Elsie and Jill and while there got flooded out of our caravan by a terrible storm. However, we got by and returned safely.

I did practically all maintenance required on these machines and learned quite a bit. I also maintained the lorry and tractor at Compton. While there I was having a go at a motor mower, went to start it by hand as they were then started, it backfired and caught my right hand which was very painful, and I now get recollections with a swollen knuckle. So, I have had some experiences in my time.

You will know that in the Second World War I joined up in the Home Guard, became Sergeant, after a time Lieutenant and was in full charge of the Tysoe Platoon. This meant that I had to train them in all their exercises and lead them too. This duty took up a lot of time for which we received no payment but were issued with a rifle and uniform. This took up a lot of time, drilling and exercising evenings and weekends. So I have never led a lazy life until my later 80s which are now a complete change for me. Anyhow, if you read and understand all I have written it will tell you that work is good for everyone, and I have done most things.

Addendum (2)

You may know that Grannie and I have now (in 1977) accomplished 65 years of married life which has been tight sometimes, but has been happy to us and we, at our age, are still quite content together and I suppose one could say, fairly healthy although not so fit as in the past. We have celebrated our Silver Wedding, Golden and Diamond with family and friends. It has all been very nice. We live in our old stone-built house, rent-free, owing to my working life at Compton and we entered here in November 1920. I continued as a guide at Compton Wynyates until I was 84 years in age which has been appreciated by the present owner whom I remember from his birth.

Addendum (3)

Now there have been three times in my lifetime when I have had to pass a test – medical – when aged 16, I joined the Tysoe branch of Ancient Order of Foresters. The doctor stated the strongest heart I have ever tested. The same statement when I applied to join the Navy, aged 15 and on entering the Army too. I would not say it is similar now – 86 years but manage to keep going although a little weaker. Half cwt is as much as I can move now whereas I have carried wheat, oats, barley by the sack full when amongst the threshing jobs.

Addendum (4)

I was working with J Philpott near to Compton Windmill doing some fencing. It was warm and we sat down on the grass to have our dinner. Suddenly a stoat appeared, dragging a rabbit, about 12 yards away. It left the rabbit and went into the wood and returned with five young stoats. They were placed in a circle round the rabbit. Then the mother stoat told them, one at a time how to spring onto the rabbit. This was most unusual and we kept quiet.

There were lots of stoats and rabbits around at that time and we were allowed to catch rabbits, so we used to set traps (wire) in their runs during our dinner time and often collected one to three the following morning. I once caught five. They were very nice to eat and we could always sell them for one shilling each in the village. I also caught waterfowl on the old mill pond. I had a little dog, Floss who would go for a swim, knowing that the fowl could only dive three times. She would go for them, then after their third dive would grab them and bring them to me.

Regarding the rabbits at Compton, they were everywhere and our Floss was an excellent catcher. I taught her how to wait if a stoat was pursuing one, until it became overwhelmed with fear and then she would go up and catch it. I have even done that myself. She used to know if a rabbit was sitting in long grass. She would approach it only on the side of a near hedge where it was likely to go and usually managed to catch it. Then she would not allow anyone to take it from her except me. She also kept anyone out of our lorry if I was absent. I once went from picking up hay above Compton Lawn, into Banbury. I left her there along with my old coat, and I returned to Tysoe as it was late. Now she knew the other men with whom I was working but she would not leave with them although they tried to take her and she was there, on my coat, the following morning