Introduction

Before the advent of Social Services, a national benefits system and even the establishment of Parish Councils, Tysoe’s local administration was handled by a committee of individuals known as the Vestry Committee – a name which reflected the fact that this committee normally met in the church vestry. The origins of Vestry Committees lie obscured in the later Middle Ages from when they evolved through custom on a parish-by-parish basis taking charge of communal taxation and expenditure in what might be considered now as a form of local government administered through the Church. Under a Poor Law Act dating from 1601 the Vestry Committee was also responsible for the poor of the parish and for collecting the Poor Rate for distribution to those in need.

Composition

Records of Vestry Committee meetings were kept in a series of Vestry Books of which one for Tysoe is in THRG’s possession. Earlier and later volumes almost certainly survive in formal archives but have yet to be accessed. This volume started in 1800 and was written up to 1826 with an odd entry for 1840 added at the bottom of one page. As the record dates below show, meetings of the Committee varied although they increased in frequency in the later years of the book. Most of the recorded entries deal with the money or goods which were to be distributed, but they also mention named individuals and places.

According to signatures at the end of each entry the Committee could consist of anything between nine to over twenty ratepayers, typically composed of those persons of higher social standing at a time when class structure was well-defined. Two of their number were elected to be Churchwardens for the year which was an onerous duty which could not be refused without payment of a fine (see discussion on Churchwarden’s Presentments for further details). A.W. Ashby, in his social analysis of the period wrote in 1912 that ‘it was hard to discover the principles on which the composition of particular bodies was based’ 1.

The entry for June 1st 1825, one of the last records in the Book, gives one snapshot of those who comprised the Committee for the following year: Mr Seagrave the vicar was proposed as the chairman, Richard Rouse and William Middleton as the Churchwardens and Thomas Gamble and Henry Walton as Overseers of the Poor. The rest of the all-male committee was Thomas Middleton, Samuel Chandler, Richard Ainge, William Ainge, Daniel Walton, S, Nicholls, Nicholas Middleton, John Greenway, Robert Wells, Simon Stubbs, John Malsbury, Clark Middleton, William Gamble, Willim Rose and John Watts. This list was sent to Charles Gregory Wade, Magistrate of Warwickshire, to appoint a ‘select vestry’ for the care and management of the concerns of the poor of Tysoe. It was duly signed on 4th June 1825.

It seems that attendance at meetings (monthly by law) was not always what it should have been: the entry for 1st October 1823 stated that absentees could be fined for non-attendance. The power and influence of Vestry Committees lessened by the end of the 19th century with the creation of County Councils and civil parishes in 1889, the Vestries’ role being split into two: the newly formed elected Parish Councils in 1894 took over secular administration while the Parochial Church Council assumed responsibility for ecclesiastical matters. This is largely the system that survives today.

Nature of records

All entries were dated and were mostly short, revealing the varied nature of responsibilities of the Committee. In some instances names of the Committee attendees were listed. In an age when literacy could not be assumed among working men written records were usually made by a parish clerk who received a small emolument for his services and who wrote in copperplate with a quill pen. The spelling was still non-standardised though the words intended were normally recognisable.

The monetary system used in the records was pounds, shillings and pence, usually abbreviated as £/s/d. This was a system that continued until decimalisation in 1971. For those unfamiliar with the units, there were twelve pennies in a shilling and twenty shillings in a pound. Halfpenny and farthing (a quarter of a penny) coins existed and appear as ½d or ¼d occasionally. A guinea was one pound and one shilling and might be written as ‘£1/1/0d’.

Reference is made to dates in common usage in England at that time. There were four dates in the year known as the quarter days, when various payments were agreed. These were Lady Day (March 25th, the first day of the church New Year), Midsummer Day (June 24th), Michaelmas Day (September 29th, the feast of St Michael the Archangel) and Christmas Day (December 25th).

Remit

The remit of the Committee was curiously ill-defined with no hard and fast rule as to what it was. Other than its obligations under the terms of the Poor Law, and for appointing Churchwardens, Overseers of the Poor and Constables, its remit appears to have been adaptable to what was periodically and vaguely defined in the entries as ‘custom’. Other responsibilities appear to have occurred on an ad hoc basis, for example needing to pay a share to repair the turnpike road (the current A422), repairing properties which had been rented to the Parish for housing the poor, managing the Sunday School, or advising villagers that travellers were not welcome in the Parish and should be reported to the Constable. The Committee also provided coal for the needy, oversaw bread production and even paid for medical care and the distribution of clothing for poor parishioners. Bizarrely, there is also a record of the Committee selecting men from the village to serve in the militia during the period Britain was at war with Napoleonic France. According to the records the Vestry Committee enacted this particular responsibility on the 3rd of August 1803. They requested men to volunteer by the following Friday evening with a draw to select from their number one, two or three as necessary. The names of those chosen were not recorded.

Economic context

Inflation varied widely over the period covered by the records and offers some context to the amounts the committee offered to pay out and the changes in the amounts payable. Relevant factors here were the demands of industrialisation and 20 years of conflict, not least being a war with Napoleon which resulted in interruption to imports and exports, shortages of food and wild fluctuation in prices. There was also a gradual population shift into towns, partly as a result of enclosures which were introduced in Tysoe in 1796 as a result of the Inclosure Act. Previously the availability of common grazing and the strip system of fields had provided a supplement for an agricultural labourer but with the amalgamation of land and the development of larger farms this was no longer possible. The resulting levels of poverty are reflected in the entries. Tysoe’s population also increased in the first quarter of the 19th century from 891 souls (1801) to 1070 souls (1821). The census also shows that in 1801 there were 584 people in the Parish working in agriculture but that there were only 195 homes to house the 220 recorded families. Climate too played a part in this period, not least the implications of bad harvests and variations in the price of flour to make bread. The climate records show extremely dry summers in 1800, 1802, 1807, 1818, 1825 (when there was such a high temperature that men and animals died) and in 1826. There were four particularly severe winters recorded in 1813/14, 1815/16, 1819/20 and 1822/23 2.

Below are a series of headings which reflect some of the areas of concern with which the Vestry Committee found itself dealing and which have been identified as being of particular interest here. They also illustrate the extraordinary breadth of its powers. Each area of concern contains a short summary followed in most cases by selected elements of entries of note or of particular interest. Square brackets are used to indicate lost or undecipherable wording.

Coal distribution

Wages and clothing for the unemployed

Housing benefits

Bread

Medical and other appointments

Apprenticeships

Income and expenses

Coal distribution

The poor needed help with fuel for heating and cooking, and the Vestry Committee had the power to order coal to be sold cheaply to the poor. It was collected from Warwick, Banbury or Stratford and was ordered by the hundredweight (cwt). The process seems to have been that either someone was delegated to collect it by the cartload or that it was ordered, together with the cost of carriage added to the bill and delivered to the ‘wharf’ in the village. This ‘wharf’ was probably the area known locally as the ‘dock’ just behind the present Village Hall. A later decision that was made for local people to collect their own coal from the wharf suggests that it had once been delivered to them. The records contain numerous and regular references to coal: information about prices and places; where the coal was ordered from, and named villagers responsible for carrying out the orders. The Book entry for 21st May 1800, for example, places an order for eighty tons of coal brought from Warwick at eight pence per hundred (cwt) for carriage but if bought from Banbury then four pence per hundred for carriage. By 1814 the amount ordered had risen to 120 tons. Later coal was ordered only from Stratford and Warwick and the coals were brought to a place to be weighed out for the poor by a particular date. Later records name the coal merchants that were used. Warwick was near the coalfields at Bedworth from where coal was taken to Coventry along a canal constructed in 1769. The canal joined the Trent and Mersey Canal and the Oxford Canal. By 1815 the canal to Stratford was completed and enabled craft to enter the Avon which was navigable as far as the River Severn and provided a network which allowed coal to reach Birmingham as originally intended. Coal could now reach Tysoe efficiently from both north and south.

Examples

May 22nd 1801. A hundred tons of coal at 17d per cwt from Warwick or Stratford was to be ordered and the collector would pay his own expenses for loading and weighing. They were to be brought about a fortnight after old Midsummer.

May 28th 1802. Fifty tons of coal were to be brought from Warwick and fifty from Banbury at 17d per cwt. The coal was to be delivered by August 12th to the place where it was to be weighed and, if not, the Overseers of the poor were impowered to go and fetch it at their own expense.

May 16th 1803. A hundred tons of coal from Banbury and Warwick, fifty from each, was to be ordered at 18d per cwt to be delivered by the 12th August with the overseers empowered to hire a carriage to fetch them if they were not delivered.

September 30th 1803. Coal was to be sold at 16d per cwt to the poor who are on the book and if there was a surplus unsold to sell it to people not on the book at 18d per cwt.

November 9th 1803. Farmers were not to bring any more coal for the poor without a ticket from the Overseer. Coal would be sold to the poor at 14d per cwt.

April 23rd 1804. A hundred tons of coal was to be fetched by the 12th of August at 8d per cwt carriage from Warwick and 4d per cwt from Banbury.

March 30th 1807. A hundred tons of coal was to be ordered from Warwick and Banbury, 8d per cwt carriage from Warwick and 4d per cwt from Banbury. It was to be delivered by 10th October and to ‘fetch their own carriage’ but if not delivered by then the Overseers were to use money out of the levies to fetch it. Any tradesman was to ‘present a received’ which was to be filed with receipts in the schoolhouse (the signatories to this include for the first time the vicar, Mr Seagrave. It suggests that proper business procedures were being firmed up).

April 18th 1808. The Churchwardens, Overseers and other inhabitants of the parish agreed that Thomas Hewens was to have the coal and to weigh it from the wagons and should be paid 8d per ton for weighing and stacking.

May 11th 1808. Overseers of the poor were to order 100 tons of coal for the poor of the parish to be brought by the 10th October. It was to be ordered from Warwick at 8d per cwt and Banbury at 4d per cwt and from no other place. If the order was not fulfilled on time then the Overseers were to go and fetch it.

May 15th 1810. Coals were to be ordered from William Humphris of Warwick and Mr. Golby of Banbury, the carriage to be paid for after the 10th of October as in the previous year (this is the first time that names as well as just the place have been specified).

April 15th 1811. Coals were to be stored in the barn the parish bought from Charles Pickering and the Old Road was to be used to access the premises. On the same date Thomas Hewens would continue to weigh the coals for the poor at the usual price but they were no longer to be stored on his wharf for which he would allow one guinea (he was the sole signatory).

April 19th 1813. Coals for the poor were to be ordered from Mr Pimm of Warwick and Mr Golby of Banbury and to be delivered one month after Michaelmas. Any defaulters were to be fined one pound by the Overseers. A bill was to be delivered with every load of coal. Coal from any other source would not be taken in at the Parish wharf.

May 12th 1813. The record notes Thomas Hewen’s resignation as weigher out of coals and the appointment of Richard Reading to do the job on the same terms as his predecessor. Richard Reading was to offer up his account every month to the Committee. The coals currently in store were to be weighed and Thomas Hewen was to deliver his account at the next monthly meeting. If Richard Reading accepted coal from any other source than those agreed by the committee at Easter he did so ‘on his peril’.

April 11th 1814. 120 tons of coal were to be ordered from Mr Pimm of Stratford and from Warwick and was to be the best coals at the price the dealers were selling at. They were to be brought by Michaelmas next.

March 25th 1816. Coals were to be brought from Warwick at seven shillings per cwt and from Stratford at five shillings per cwt. There was no mention of the quantity ordered (this seems an astonishing increase in price from previously).

March 24th 1824. Coals were to be brought from Stratford and Warwick at 4d per cwt from Mr Pratt. Every farmer was to bring them between the 25th of March and the 25th of December, the whole quantity to be 100 tons.

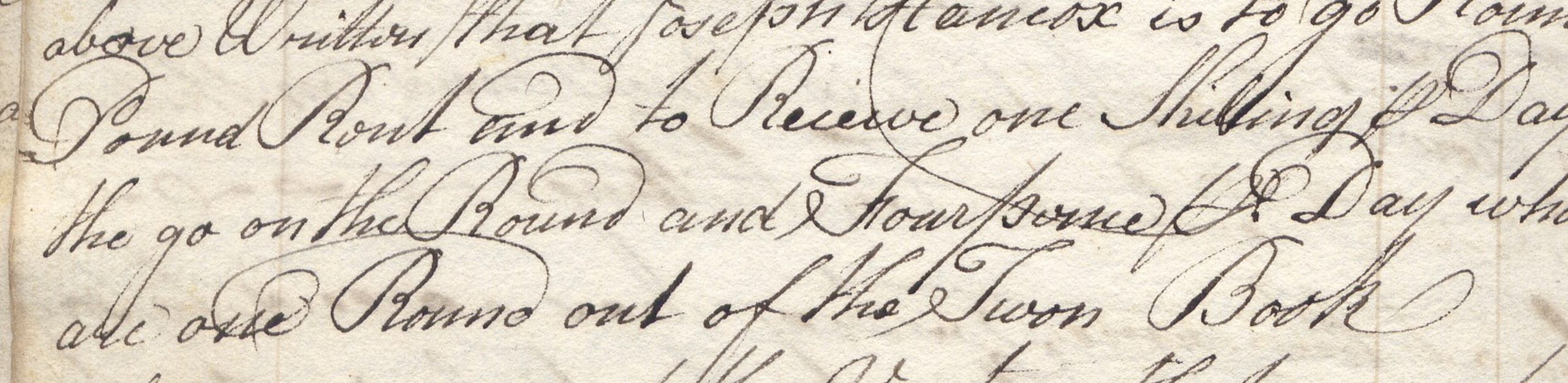

March 30th 1825. Thomas Hancox was to be paid one shilling to stack the coals and the coal price was to be raised by ¼d per cwt (this suggests that the poor were expected to contribute to their coal and always had done. This is the first occasion this is mentioned in the records).

Wages and clothing for the unemployed

There are references to amounts of money to be paid out to the unemployed, to those who were too old or infirm to labour, or to those for whom the Committee found work. Clothing was sometimes paid for by the Committee and the list of recipients effectively represents a list of the poor. There are references to ‘apparel’ which seems to indicate working garments. The record for 21st May 1800 recorded that ‘all manner of wearing apparel’ was to be provided for Elizabeth Blackford when she was sent to live with John Watts, and that her living expenses of fifteen shillings a week was to be paid to him until St Michael’s day. Elizabeth Lont and Sarah Brown received a similar offer on the same date. By October 1824 those given apparel for work purposes had to return it if they were no longer employed there. John Townsend and John Tysoe were to ‘have a shirt’. The widow Goddard’s daughter was to keep her service with Thomas Hewens in the Back Lane and have ‘a few things’ of the Overseers of the Poor. The record for 15th May 1801 agreed that Elizabeth Blackford should receive a ‘shift’. The Committee also paid sums of money to householders who provided beds, food and laundry facilities for allocated men or women (e.g. see entry for 12th October 1807 below). There are some indications that the cared-for inhabitants were moved on after an allotted period.

There are several references to people going ‘on the round’. This seems to mean that jobs or lodgings were found for the unemployed, and named people were allocated to a particular employer or householder with money offered for their keep. The amount of time they were to stay before being moved on was specified: hence going ‘on the round’. For example, in November 1800 Joseph Hancox was to go on the round and receive a shilling a day whilst on the round and fourpence a day from the Town Book. The names of those accepting the poor on the round seem mostly to have been those on the Vestry Committee, presumably because they were the principle employers in the district and prepared to find small jobs for those who were not able to earn a living on their own account. By 1820 the ‘round’ system appears to have vanished altogether in Tysoe.

A key requirement of the 1601 Poor Law Act was that each Parish should care for its own, but this failed to stop some individuals moving from parish to parish to obtain the best benefit they could get. The Settlement Act of 1662 put a stop to this which would explain one particular record here. The entry dated May 18th 1821 allowed a certain Richard Coles to be to be provided with £5 to remove his family to London and, provided he could satisfy the Vestry that he has been accepted by the parish there (essential under the Settlement Act), he would receive a further £2/10/0d and the Parish of Tysoe would accept any further maintenance charges for the child left in Tysoe that he had agreed to maintain.

In the later entries, there seems to have been an early form of family allowance benefit whereby a household with children could be supported, the father receiving a given amount, the wife generally a smaller amount and children even less per head. There is a notable change in 1818 when it is clearly stated that no able-bodied man would be entitled to help from the Parish Book. By 1823 the wages were laid down and, interestingly, included a rate of payment for catching sparrows and snakes which were presumably considered pests. 1823 also saw a proliferation of statements about pay from the parish. The revised thoughts evident in the records suggest disagreement about the needs of the poor and balancing the books.

Examples

May 15th 1801. Men and boys were to go on the round as usual but for half the time.

April 19th 1802. Those who went on the round were to go to every farmer and occupier of land in proportion to what they wanted at a rate of 16d per day for those capable of a full day’s work and that old men and boys would receive half that sum. The Poor rate was to be used to make the calculation.

October 24th 1802. John Caselo [?] of Woolford was to have his grand-daughter at two shillings per week until Christmas. On the same date Ann Walker who was at Francis Hancox’s was to go to John Walker Jnr. Tayler at 1s 6d per week until Old Saint next and she was to be provided with all manner of wearing apparel.

May 16th 1803. The Committee appeared to have some arbitration role agreeing with a neighbour that Mary Mousley ‘should be brought herewith’, as she was ‘good for nothing’ and that Mr Greenway could deal with it.

October 12th 1803. George Foster was to continue at Mr Middleton’s until Old St Michael (St Michael’s Day) at two shillings per week and to provide all manner of wearing apparel for him. John Dodd was to go to Richard Ainge at two shillings a week until Lady Day, thereafter to be paid 18d per week until Old St Michael. He too was to be given all manner of wearing apparel. Nicholas Middleton was to have John Wells at one shilling per week to Old St Michael next, with the parish to provide wearing apparel. Simon Hewens was to have Wiliam Dodd for one guinea till Old St Michaelmas next, Hewens to pay the guinea as noted. The parish was to provide wearing apparel for Dodd. William Greenway was to have Robert Foster at one shilling per week until St Michaelmas next with the parish providing wearing apparel. Thomas Townsend was to have Charles Foster at two shillings a week until Michaelmas next and the parish was to find him wearing apparel.

November 17th 1803. William Hawtin was to have Ann Walker at 18d a week to Michaelmas next and she was to be found all manner of wearing apparel by the Parish.

November 9th 1803. The record states that those on the round would be paid where they were and must move on at the given time.

December 19th 1803. Old men on the round were to be paid 6d a day where they were and the rest out of the Book. Boys on the round were to receive 2d a day and 1d out of the Book. (It would be interesting to know how ‘old’ was defined).

April 2nd 1804. George Penn’s son Thomas was to go to John Poulton in Lower Tysoe at a shilling a week until Michaelmas next.

October 23rd 1806. John Dodd was to go to William Hawtin who would give him a guinea at Old St. Michaelmas next with the parish finding his apparel. William Mole was to go to Edward Watts under exactly the same conditions.

April 15th 1805. Robert Foster was to go to Nicholas Middleton at one shilling a week until Easter 1806 with all manner of wearing apparel. John Dodd was to be sent to William Hawtin until the 10th of October 1806 at two pounds two shillings, George Foster to John Poulton for four guineas and a half, Samuel Carter to Simon Hewens for nothing, William Mole to Edward Watts for 18d a week to Easter and John Penn to Thomas Townsend for a shilling a week also to Easter.

October 14th 1805. John Claydon was to go to Thomas Middleton at 1s 6d per week until Easter and William Hawtin was to have Ann Walker for nothing till Michaelmas with clothing provided for her by the parish. Ann Walker was sent to Thomas Walton for nothing to Michaelmas next with the parish providing her apparel. Thomas Townsend was to have John Penn and pay him a shilling a week to Easter next. John Cleydon was to go to Robert Wells until Michaelmas next at 1s 6d per week. Nicholas Middleton was to have Robert Foster until Easter next at one shilling per week, with the parish finding him all manner of wearing apparel (the differences in pay and whether or not clothes were provided are never explained but were presumably based on personal knowledge of individual cases. Where no wage was being offered the worker allocated would be getting board and lodging).

April 15th 1807. Thomas Penn was to have John Dodd for his victuals and to be given three pounds a week to mend and wash for him. Thomas Hewens was to have Richard Goddard at 18d per week till Old St Michael next and his apparel would be provided. Thomas Middleton was to give John Cleydon two shillings per week to Old St Michael next. John Cleydon was to go to Nicholas Middleton and to give him two shillings per week. Edmund Watts was to give John Collins two shillings per week to Old St Michaelmas next. Robert Wells was to have John Wattson and give him two shillings per week till St Michaelmas next. [forename overwritten and unclear] Middleton was to have Samuel Carter for two shillings per week until St Michaelmas. Nicholas Middleton was to have Robert Foster until St Michaelmas at six pence per week and the parish was to provide all manner of wearing apparel. Richard Ainge was to have William Greenway’s son William and give him a shilling a week till Old St Michael next.

October 12th 1807. Thomas Townsend was to have John Penn and £1/1/6d to St Michael next with responsibility to wash and mend him. Charles Pickering was to have James Hiron at £1/6/6d of the parish to wash him, mend him and lodge him. John Cleydon was to go to John Poulton who would receive one guinea from the parish to find him maintenance and wash and lodge him. William Mole was to go to Mr Grant under the same terms as John Cleydon. Richard Baldwin was to receive two guineas from the parish next Michaelmas to feed, lodge and wash Richard Goddard. William Callicott’s son Richard Callicott was to go to Edmund Watts who would receive five shillings and sixpence at Michaelmas next, providing Richard with maintenance and lodging, mending and washing him. Francis Hancox the son of Francis Hancox was to go to Richard Ainge who would be paid £1/15/0d at Michaelmas next by the parish to give him maintenance, lodging, mending and washing. Richard Seden’s son Joseph was to go to Nicholas Middleton who would be paid £2/10/0d at Old St Michael next for providing maintenance, lodging, mending and washing.

July 3rd 1809. Sarah Irons was to go regularly round and be paid 8d a day by whoever was employing her.

April 23rd 1810. The notion of building a workhouse was mooted. A committee was chosen to find land, borrow money on the security of the Parish for defraying the same. Any five of the committee were empowered to act together (there are no further references to this idea which was presumably abandoned. The records for Shipston Workhouse indicate that Tysoe residents were sent there. The records are in Warwickshire County Record Office).

February 4th 1818. No able-bodied man who could do a day’s work should receive round money from the Parish Book and that old men who go on the round would be paid by their employer. The old men would go but half their round to each house.

March 25th 1818. All men, boys and girls out of employment should have to walk from the coal barn as far as the Red Lion Inn in Middle Tysoe and stand there for ten hours from the above date each day till Michaelmas next. There would be no pay from the parish if anyone entered a house during that time. Mealtimes would be nine to ten and one till two. Men were to go to the Overseer or Paymaster for their pay or complaints. Exception would be made in case of illness. (The proposal seems very harsh and, since there is a statement about expenses for vestry business on the same document, it seems that money may have been tight, possibly due to rising unemployment and more calls for help).

April 8th 1818. Abraham Pilkington was to go on the round and receive four shillings a week from his employer, Samuel Randle six shillings, John Wilkes four shillings, John Edwards four shillings, William Caldecott five shillings and Robert Usher four shillings. Boys Thomas Hancox, William Townsend, George Fessey, Henry Stiles, William [?] 3d and Mary King 2d from their employer.

April 16th 1823. Samuel Caldecotte was to receive five shillings for shoes.

April 30th 1823. The Committee agreed that a man and his wife would receive five shillings, six shillings if they have one child and seven shillings if they have two. If the families were larger then the man and his wife would receive four shillings and 1s 6d for each of their children. If the man was working then he would receive five shillings where he worked.

May 28th 1823. A man and his wife would receive five shillings, with one child six shillings, with two children seven shillings and with three 8s 9d. All able men were to receive five shillings for their work.

June 11th 1823. A man and his wife would receive five shilling, with one child six shillings, with two children 7s 6d, with three nine shillings, with four eleven shillings, with five 12s 9d and with six 14s 6d.

June 25th 1823. All able-bodied men were to be started at 9d per week and the head money was to be made up to seven shillings if the family reached it. Sparrows were to be paid for at 3d a day and snakes at [one guinea?] each (presumably these were considered pests). Each man that mowed was to be allowed nine shillings a week. Mary Powell was to have a sheet and Joseph Hancox a pair of shoes. The mowing was to start on the 30th.

July 23rd 1823. Pay was to remain as before. Vestry meetings were to be held at 8 o’clock on Friday mornings. All men who were not at work or go round were to have pay lowered by one shilling a week.

July 9th 1823. Pay was to remain as before and John Edwards be allowed one quarter’s rent.

August 29th 1823. Men who were absent from the parish for a week were to have their collection stopped while they were away (presumably they may have been working on a farm elsewhere during harvest season).

September 17th 1823. Payments for the poor were set out with men started at nine shillings a week, a man and his wife five shillings, with one child six shillings, with two children seven shillings, with three children 8s 6d, with four children ten shillings, with five children 11s 6d, with six children thirteen shillings, and widows who can work two shillings. Young women were allowed one shilling.

October 15th 1823. The parish allowance was to be as previously stated: two shillings each for man and wife and 1s 6d per child, the men to receive six shillings where they worked and where there is only a man and wife five shillings (changes like this suggest there may have been disagreement within the Vestry Committee itself).

October 29th 1823. William Smith of Radway was to have ten shillings to pay the nurse for waiting on his family. Thomas Tarver was to have ten shillings. The head money was to remain as before.

November 12th 1823. The head money was to remain as before. Girls over ten years of age were to have one shilling to stay at home. Elizabeth Matthews was to have four shillings.

November 26th 1823. The records made it clear that parishioners who kept a dog will not be given money or a job (presumably it was felt that the parish rate should not be paying for dog food?).

December 10th 1823. Pay rates were to remain as before. William King was to have one pound to keep of the parish for twelve months and William Greenway was to have 2s 6d per week while unable to work.

December 24th 1823. Pay for the parish was to remain the same. Mr William Smith was to work at Mr Hawtin’s at Westcote at four shillings a week until he was better. The men [set?] at work were to have only five shillings a week.

January 3rd 1824. Men were to have seven shillings where they worked. The family and collection was to remain as before, the children were to have 1s 8d a head. The men’s pay rate was to take place from the previous Monday.

January 14th 1824 . Pay was to remain the same but William Smith who was ill at harvest time was granted a pound for being unable to work then.

July 11th 1824. The girls that had been at one shilling per week were to go round and have 2d where they work and made up to 1s 6d with girls that work to get 1s 8d. Other pay was to remain the same.

March 10th 1824. Pay was to remain the same and Thomas Tarver was to have two shillings per week.

April 14th 1824. Pay was to remain the same except that Thomaas Greenway was to be given ten shillings in consideration of his family’s illness. A pair of sheets were bought for the use of the parish.

August 18th 1824. Widows who worked were to be deducted 6d a week, the men were to have two shillings during harvest week, strong girls 6d a week and little girls 9d. The other head money was to be as before.

October 13th 1824. Head money for a family was to remain the same. Girls who stayed at home were to have one shilling a week and old men who could not work three shillings a week.

October 27th 1824. Clothes bought by the parish for boys and girls who went into service were to be returned if they did not stay in their places.

November 24th 1824. All able men were to have eight shillings a week and head money was to be made up from that sum. Head money was to remain as before from Monday November 15th.

December 6th 1824. Head money was to be raised to 1s 9d for children and two shillings each for the man and woman. Thomas Townsend was to have 1s 6d per week.

March 30th 1825. All men were to receive nine shillings per week for that fortnight and the head money was to be raised to 10s 1d or 1d per head. (It is unclear what this means, possibly that the 1d per head was the extra rate for children?)

April 13th 1825. Girls who were able to go to work were to receive 2d a day and 2d out of the Book.

June 9th 1825. All able-bodied men were to have eleven shillings per week until harvest commenced.

September 7th 1825. Men were to receive nine shillings per week for one month and parish officers were to receive seven shillings at Warwick, five shillings at Wellesbourne and five shillings at Kington (Kineton).

Housing benefits

For some parishioners help with the rent was available and this appears to be independent of payment for work. Oddly, there is a gap of 20 years in the record of these payments and it is unclear as to whether any discussions took place in the intervening period. The people to whom the rents are paid seem to be members of the Committee who presumably are landowners as well as householders. There is no indication as to the size of families but payments are to the head of the household and may differ according size and condition of dwellings.

Examples

November 1800. At one meeting it was agreed to pay a year’s rent for several householders. The rents are not for the same sum: William Freemans 16s 3d, Richard Durham £1/10/0d, John How £1/10/0d, George Penn £1/15/0d, Richard Allcock 17s 6d and a guinea towards Edward Greenway’s rent. William Mole was to have his rent paid to Mr Gardner of Oxhill at £1/10 /0d a year and Edward Wilkins was to have £1/10/0d a year paid to Richard Colcott for his rent.

March 12th 1802. It was agreed that Joseph Hancox’s rent of £1/15/0d to Charles Pickering would be paid for a year.

September 1803. The committee agreed not to pay rents or house rents for William Randle, Richard Durham, Edward Wilkins, Thomas Malet, Joseph Grimmells[?], Francis Hancox, John Eddon and William Collicutt.

April 16th 1823. John Edwards was to receive ten shillings towards his rent.

July 9th 1823. John Edwards was to be allowed one quarter’s rent.

November 12th 1823. John Edwards was to have thirteen shillings for a quarter’s rent (this would indicate a rise of some 30% since April).

April 14th 1826. The rent is agreed on three cottages in Middle Tysoe. William Caldicott is to pay 10d at 9d in the pound, John Hancox at 9d in the pound and John Palmer 8d at 8d in the pound.

Bread

Bread was purchased and allocated by the Committee but only appears briefly in the records. There is reference to buying corn to make into bread which required two farmers to be appointed to inspect the corn and two to help carry it. The whole process was taken very seriously. The Churchwardens and Overseers collected a levy for as much as was necessary to supply bread for those in need and they expected to buy seven pounds of bread for a shilling. A maximum of £200 at lawful interest was borrowed to ‘carry on the Bakehouse’ under a management committee of named members of the Vestry Committee. They were responsible for checking the bakehouse project and supplying a quarterly account. Five shillings was put aside for the expenses of those collecting the corn from market. An agreement was made with a baker to bake the bread, and the sub-committee checked that each stage of the process was carried out. There is a very detailed account of allocating one of their number to escort the corn to the mill, to check the weight of the flour, take it to the baker and check the weight of bread returned by the baker. The possibility that someone might cheat the Vestry Committee was clearly present in their minds. Bread was supplied on Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays.

A provision was made that a general Vestry meeting could be called if it was necessary to amend the scheme. This was signed by the Reverend Seagrave and fifteen of the committee at the end of an unusually long account. The possibility of the Committee having its own bakery was mooted in October 1801 but deemed too expensive to pursue. Named people were responsible for distributing the bread to the poor. It seems that a ‘parish loaf’, as this bread was known, was larger than an ordinary loaf. A bread deliverer in the late 1960’s noted that there was a little ‘½’ on the orders for his round when he delivered a loaf. He asked why and was told that it was there because the loaf he was delivering was half the size of a parish loaf. There is no mention of bread in later documents although it is not clear whether bread was no longer offered or because payments to the poor were expected to cover the expense.

Medical and other appointments

There were various responsibilities in the village and the Vestry Committee appointed people to the posts and fixed the remuneration for the job. These appointments included Churchwardens, Overseers, and Constables of which there were three, one each for the three Tysoe villages. Perhaps more significantly the Committee undertook responsibility for medical care for the parishioners. There is mention of specific cases and reference to the appointment of medical practitioners to look after the paupers at an agreed annual fee. Two practitioners are named in 1802 but all subsequent appointments are for one. The practitioner was to provide medicines but with extra fees for dislocations, venereal disease, midwifery and fractures. For some years this is stipulated but then shortened to terms ‘as before’. There is an increase in salary from four and a half guineas (£4/14/6d) to ten and a half guineas (£11/0/6d) between 1802 and 1804 and it was still the same in 1814. In 1820 Dr Shelswell was paid thirty guineas (£31/10/0d), presumably as the only doctor appointed and as his responsibilities were greater. Regulations for consulting a doctor were tightened up in 1807. The poor were only to see the appointed surgeon and would need a ticket to go and see him or else pay their own fees. Medicine too could only come from the named doctor.

Examples

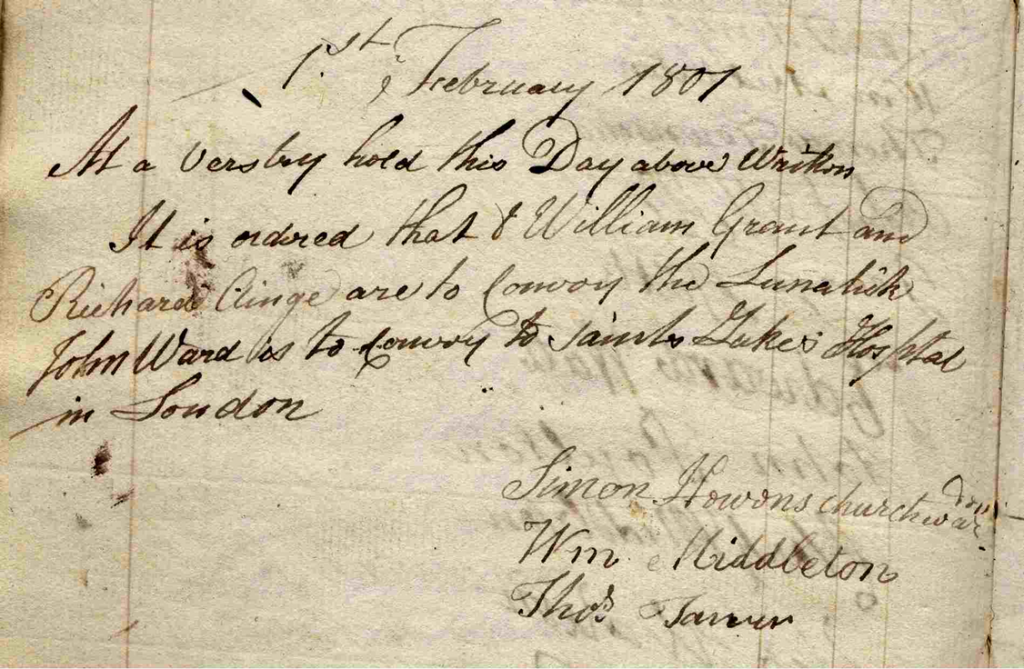

February 1st 1801. Hannah Weaver was sent to Banbury to see Mr Stones for the very bad humour in her eye. They sent ‘the lunatick John Ward’ under escort to St Lukes hospital in London as it had a reputation for dealing with patients who were mentally ill. He had an escort of two men for the journey, who were paid.

Easter Monday 1802. Surgeons Meads and Shelswell were appointed at a salary of four and a half guineas per year to provide care and Medicines for the poor of the Parish. They received a yearly allowance but agreed extra fees for some named diseases e.g venereal disease, dislocations or broken limbs and midwifery (if any). The agreement was signed by both doctors.

March 25th 1818. There was an addition in the margin written sideways and dated agreeing that smallpox and contagious diseases and accidents would incur extra fees. This was signed at Edgehill by Mr Shelswell.

April 2nd 1804. Mr Shelswell was nominated to be surgeon and apothecary for the poor of Tysoe at an increased rate of ten and a half guineas with the same exclusions as in 1802.

Date unclear. Mr Shelswell of Burdrop was again the appointed surgeon for the poor at ten and a half guineas a year. The poor were not to go to any other apothecary without the express permission of the Overseers or the Churchwardens. The usual exclusions would be paid as extra expenses if necessary.

March 30th 1807. Dr Shelswell was appointed to continue at ten and a half guineas a year (£11/0/6d) and paupers were to get a ticket from the Overseer to go and see him. If they consult anyone else they had to pay that bill themselves.

December 3rd 1810. Mr Edward Watts and Mr Nicholas Middleton were to act as Constables and Mr William Middleton as ‘scythingman’ (presumably for keeping the churchyard grass in order).

April 15th 1811. ‘It is unanimously agreed that the Constable is to pay the County rates into the hands of the Chief Constable and not to either of the Overseers’. (Presumably there was some concern that the overseers would use the money for other purposes).

December 8th 1815. The Committee nominated and appointed Mr Daniel Walton and Mr William Rose as Constables for the year forthcoming.

March 25th 1817. Mr Shelswell was to provide medicine and attendance for the ensuing year for eleven pounds.

March 29th 1820. Mr H. Shelswell was to continue to treat the paupers of Tysoe for thirty guineas a year for everything, including fractures, broken bones[sic], vaccinations, smallpox, all cutaneous disorders and midwifery where the midwife was deemed not competent or of sufficient [word ‘experience’ perhaps missing]. Mr Shelswell’s signature was witnessed by Richard Reading.

March 29th 1821. The committee nominated and appointed three constables: Richard Rouse for Upper Tysoe; Thomas Middleton Junior for Middle Tysoe and Mr Nicholas Middleton to ‘the third borough’.

March 25th 1822. Mr Shelswell was re-appointed for £25 for the year ensuing to perform the usual tasks. Mr Shelswell’s signature was witnessed by Richard Reading.

March 1823. The meeting appointed Mr John Greenway, Mr Thomas Middleton and Mr Richard Rouse as Constables for the year ensuing.

March 20th 1824. The committee nominated and appointed Mr Clark Middleton, Mr William Hawtin, Mr Nicholas Middleton and Mr John Malsbury to serve as Overseers of the poor for the year ensuing. Mr.William Middleton and Mr. William Ainge were appointed Churchwardens and Mr John Greenway Constable for Upper Tysoe, Mr William Gibbs for Lower Tysoe and Mr John Watts for Middle Tysoe.

March 24th 1824. George Ainge was appointed assistant overseer at £19 a year (this may indicate the higher work load in relation to the lower pay of the Overseers appointed four days earlier). Mr. Shelswell was to attend the poor of Tysoe for £24 for the year for all cases.

March 25th 1825. Richard Rouse and William Middleton were elected churchwardens and Henry Walton and Thomas Gamble were elected Overseers of the poor. The constable for Upper Tysoe was George Ainge, Church Tysoe William Page and Lower Tysoe Daniel Walton.

November 13th 1826. There was to be treatment against smallpox ‘cut for the cowpox’. This was to be done by Mr Welchman or Mr Cawley, whoever will do them more cheaply. For the first time one of the signatories is a woman, Mary Ballard.

Apprenticeships

Apprentices were selected and supported for both boys and girls. In 1804 mention is made of representatives of the Feoffees (now known as the Tysoe Utility Trust) being responsible for one apprenticeship whilst the Vestry Committee sponsored another. The places where apprentices were sent seem to cover quite a wide geographical area, from London to Warwick. It is not known from where the committee received information about available apprenticeships.

Examples

August 17th 1802. It was agreed that Charles Foster who was at the Widow Claridge’s should be apprenticed to Mr Smart at Warwick in the cotton manufactory if they could agree terms.

August 17th 1804. Apprenticeships were provided for two residents to go to Middlesex in London. Isaac Townsend was to go to Daniel Crofts to learn the ‘art or mistery of cordwainer’. He was to stay until he was 21 and Daniel Croft was to receive ten pounds and then £5 after two years. William Townsend was to go to Mr Hains until he was 21 for £15 and £2 to be allowed for clothes. He was to be supported by the Feoffees.

October 19th 1804. Charles Foster and Robert Foster were to be offered apprenticeships to shag and worsted weavers on the agreed terms (unspecified here) providing the neighbours agree. One would be supported by the Overseer and the other by the Feoffees.

June 19th 1808. The overseers Robert Wells and Clark Middleton agreed that they would have a meeting about apprenticing poor children from the parish of Tysoe. On the same document there was a list of children they nominated on June 24th 1808 signed by the churchwardens John Hewens and Richard Baldwin as well as the Overseers. They nominated George Foster, Isaac Clifford, John Wilks, William Mole, Richard Hirons and William Cleydon. (There was no further mention of whether these apprenticeships took place or with whom).

October 19th 1810. There was an agreement at a meeting with parish officers and neighbours with Thomas Geddes that he would take Maria Ashfield as his apprentice for the sum of seven guineas for seven years. He agreed to teach her his trade as ‘glover and taylor’ and to provide for her necessities during that period and two sorts of wearing apparel when she completed her apprenticeship.

June 5th 1816. Sarah Caldicott, daughter of Richard and Mary Caldicott of Upper Tysoe, was to be sent as an apprentice to Mr Smart at the cotton mills at Guyscliff in Warwick.

Income and expenses

The manner in which the Parish income was derived seems to have been less well recorded in the Vestry Book than how it was spent. Although there are references to money being paid for rent to properties owned by the parish there is no complete list of the properties, nor is there a list of those who were taxed. There is, however, the occasional reference to consideration of legal action being taken for non-payment. Being locally managed, the way money was allocated from the Poor Rate, could be a somewhat contentious issue. Parishioners could see exactly what, or who, the money was being spent on, and those who paid the rate were sometimes reluctant to make payment as a result. The payment of expenses may also have been a contentious issue, and the record is often clear about what was payable as an expense and what was not.

Examples

March 12th 1802. The entry records a debate as to whether the committee should take Mrs Wilcox to Warwick Assizes to make her pay for her daughter Mrs Judges’ maintenance.

April 2nd 1804. It was permitted that the Overseers could spend 5/0d at their meeting but any excess cost would come from their own pocket. The record does not state what the money was for. A further record on the same day declared that they would spend four guineas and meet any further sum from their own pockets.

April 23rd 1804.The committee agreed that the Overseers of the poor and the Constable should be allowed to spend out of the parish book five shillings to go to Warwick or Wellesbourne or Halford. There is no indication as to why they needed to go there.

April 18th 1808. It was agreed to nominate the Overseers and the Committee was pleased to have appointed someone to collect the poor levies and pay the poor under the direction of the Overseers.

August 2nd 1813. The Committee agreed to transfer the tenancy of the house, malthouse, garden, orchard and stall from Mr Thomas Nash to Clarke Middleton at Michaelmas next with an annual rent of £15/15/0d. The parish was to pay for repairs to the house with the tenant responsible for those matters relating to convenience.

January 8th 1817. The committee agreed that the barn they bought from Thomas Clarke would be converted into two cottages with woodwork being done by Thomas Collcott with repairs to two neighbouring cottages being done at the same time. The work was to be completed before the 25th March next.

March 25th 1817. It was agreed that no more than five shillings would be spent on the parish account at monthly meetings (again there is no statement as to what the money was for).

March 25th 1818. The committee stated in no uncertain terms that no money should be spent on the Vestry meeting or any other meeting on parish business from the parish. Coupled with a tightening of conditions for the unemployed on the same document it would seem that the Parish was running short of funds.

May 3rd 1820. The committee agreed that Mr William Whateley of Wellesbourne would come and assess parish lands and houses for a fresh rate for the poor.

June 30th 1820. The parish agreed to giving the Overseers and Churchwardens permission to purchase three cottages in Upper Tysoe from the estate of the late Charles Pickering if they thought it proper.

June 6th 1821. The committee agreed that all ‘our parishioners’ and all ‘other parishioners’ who could afford to pay would pay the poor rates set by Mr Whately and those who were unable to pay would be excused. Mr Thomas Smith and Mr William Gamble objected but had not cleared up their rates. (The ‘other parishioners’ are possibly those who attended the new Methodist chapel or the Roman Catholic church or those of other faiths who go elsewhere but live in the parish).

March 25th 1822. The Constables were to be allowed seven shillings to travel to Kineton to pay the rates and the same amount to travel to Warwick for their officers. Five shillings were allowed for travel to Shipston and to anywhere more than five miles from Tysoe.

July 3rd 1822. This entry is very formally set out in beautiful handwriting. It commences ‘At a Vestry Meeting of the Inhabitants of Tysoe holden this third day of July in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twenty two agreeably to publick notice given in the Church the last preceding Sunday, for the purpose of determining upon a mode for accommodating and settling the objections to the rate or assessment made for the relief of the Poor of the said Parish dated the twenty second day of June 1821.’ It was decided to ask Mr William Whateley and John Davis of Bloxham to revise and, where necessary, to adjust and correct the assessment, having power to inspect the farms, lands and tenements and read such evidence as tendered to them. If they could not agree, John Greaves of Barford was to be called upon to arbitrate. Their judgement was to be binding and conclusive to all and was to be backdated to 2nd June 1821. Costs for the new assessment would be borne by the rates to be assessed for the relief of the poor of the parish.

March 21st 1823. Mr Thomas Middleton senior and Mr Thomas junior were appointed to serve the office of assessors of land and assessed taxes for the year ensuing.

April 2nd 1823. The committee appointed an assistant Overseer, George Ainge, to pay the poor at the rate of £19 per year. The Overseers were John Malsbury and Daniel Walton.

March 25th 1825. It was agreed to pay the Overseers two pounds per annum for which they were to collect the levies and pay the poor.

July 23rd 1840. Mr Thomas Middleton was appointed chairman. One resolution was that J. Hewens senior was to go and see Mr. Hands about selling the houses that the parish bought in 1810 and to ask him to give time to make up the money borrowed from him. After Mr Hewens had consulted Mr Hands the undersigned agreed to sell the messuages to both houses. (This 1840 record was added to an existing page in this Book, presumably because the correct book was not available at the time.)

An undated entry lists names against sums of money. There is no explicit indication as to meaning but it almost certainly denotes the amounts expected from various parishioners towards the poor rate. The names are mostly those of the Vestry Committee and would appear from the names of the employers who accepted those on the round to be farmers or other employers. The amount totalled £11/3/6d. There are various other jottings on the page (not listed here).

Mr William Gardner ……… 5/0d

Do. arrears ……………………. 10/0d

Mr William Anchor ……….. 2/0d

Mr Chambers ………………..10/6d

Mr John Hewens ……………. 7/6d

Mr Leigh …………………. £2/2/6d

Mr Ballard ………………….. 10/6d

Marquess of North. … £4/4/0d

Mr Nicholls …………………. 10/6d

Mr Townsend …………………5/0d

Mr Thomas Middleton .. 10/6d

Mr William Hawtin ………. 7/6d

Mr William Middleton …. 5/0d

Mr William Gamble ……. 10/6d

Mr Edward Watts ………… 7/0d

Mr William Rose …………. 5/0d

Mr Thomas Walton …….. 2/6d

Mr Henry Walton ………… 2/6d

Mr Richard Baldwin …… 5/0d

Conclusion

The Vestry book is essentially a record of decisions made by a committee who were familiar with all aspects of Tysoe parish life and, it would seem, of the parishioners who lived there. As an historical document, although it provides a fascinating insight into parish life and how changing circumstances were managed, it takes for granted a wider knowledge of the parish context and leaves many questions unanswered. For example, how many paupers were there at any given time, how many rate payers, how much was annual income and how much annual expenditure? Did the unemployment rate rise due to inflation? Were there ex-soldiers returning to the village with the peace of 1815? Exactly what property did the Parish own? In many respects the Book is little more than a set of notes written as briefly as possible to fulfil a legal obligation not to satisfy the enquiring minds of 21st century historians. That said, the pages are filled with names and places that serve to bring the early 19th century history of Tysoe alive.

Sue Hancox for THRG

October 2023

Uploaded October 23 2023

- Ashby A W.,1912. ‘One hundred years of Poor Law administration in a Warwickshire village’, (facsimile edition Vinogradoff P. ed, Oxford Studies in Social and Legal History, Vol III, Elibron Classics, Oxford 2005). ↩︎

- There are various websites that list and comment on historic climate changes. The one used here was https://premium.weatherweb.net/weather-in-history-1800-to-1849-ad/ which offers some evidence of the weather which affected crop growth from year to year. It has a caveat that most of the records relate to London but there are some general comments. ↩︎