Myth, History and Landscape

This is a distilled text from a series of presentations delivered at the Village Hall, Tysoe by the Tysoe Heritage Research Group (THRG) on Saturday 19th July 2025. Talks were delivered by John Hunter, Gill Stewart, David Freke, Rosemary Collier, David Low, Susie Carrdus and Kevin Wyles.

Much of the raw data for earlier research into the Red Horse carried out by Kenneth Carrdus and Graham Miller was kindly made available by Susie Carrdus and Kevin Wyles.

Follow the links below to view the various sections:

Background

Art in the landscape

The escarpment through the ages

The horse

The timeline

The work of Carrdus and Miller

Where next?

Background

Over the last few years THRG has undertaken a number of major research projects in the village and parish. These have included a detailed survey of some 1500 graveyard and church memorials, an investigation into the origins and dates of around 350 field names, the results and impact of the Inclosure Act, and Tysoe’s diaspora to New Zealand in the late 19th century. This present topic on the Red Horse of Tysoe is one which was seen as important not only to re-establish the local and national significance of the Red Horse but also to bring to the fore previous work that had been carried out and was in danger of being forgotten.

Today there is no visible Red Horse on the landscape. It survives as a geographical area (the Vale of the Red Horse), as a local political entity (the Red Horse Ward), as a prancing stallion on the Tysoe Primary School blazer, in the name of the village surgery and as a major local supplier of fuels, timber and farming materials (Red Horse Vale, also kind sponsors of the event). It seemed an opportune time to revisit the whole concept of the Red Horse and its place in mythology, history and on the landscape.

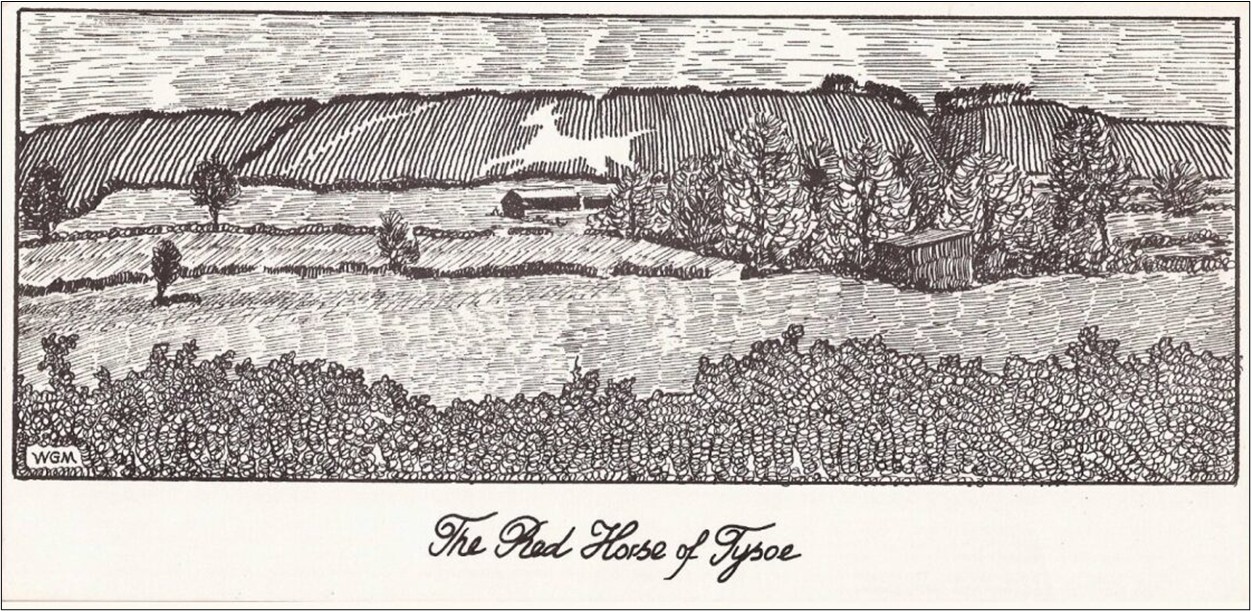

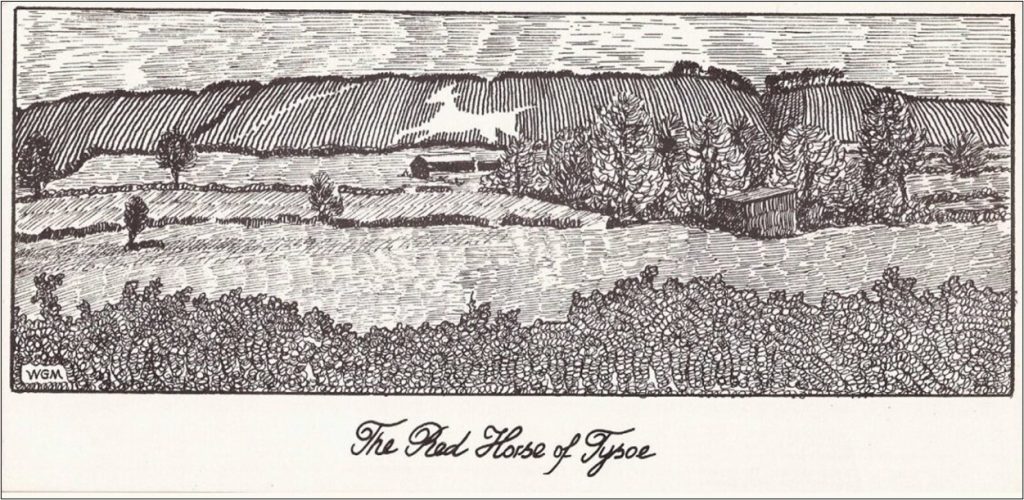

Much is known and much is unknown. No-one alive has ever seen the Red Horse but the general consensus of opinion, both historically and anecdotally, places it etched into the west-facing escarpment above Old Lodge Farm overlooking Lower Tysoe. Its redness is generally agreed to be the result of exposing the red iron-rich soils on the escarpment, although this has now been found to be a more complex phenomenon than originally thought (See The work of Carrdus and Miller). From all accounts it was a massive landscape feature, arguably over 80m across from front hoof to end of tail as depicted, and over 50m tall. This makes it slightly larger than Tysoe’s medieval parish church. At that size it could be seen for miles around, easily visible from the Old Salt Road (now the A422) and even from the Fosse Way, bearing in mind that before the field inclosures of the late 18th century the open landscape would have provided greater uninterrupted lines of vision than today.

A monument of this size provokes a number of interesting questions, not least regarding the name and status of the person who commissioned it or arranged for it to be created. A feature of this magnitude requires organization, funding and considerable human effort, research showing that the extent of the labour involved in its creation was much greater than originally estimated (See The work of Carrdus and Miller). Was this person a local worthy intent on perpetuating his or her life in the form of a folly? Were they from Lower Tysoe from where the inhabitants could directly see and marvel at such an achievement? Would that explain its location on the escarpment rather than displaying it further to the north or to the south? Why there? Was the originator also the landowner, or is the reason completely different, for example perhaps it was common grazing and the result of a community effort to commemorate some notable event?

Questions have to be asked too about the outline of the horse itself. The head appears to be on the left in common with most other landscape horse depictions, although some others show the head on the right (See Art in the landscape). Is this an arbitrary decision by the person who designed it, the result of left- or right-handedness, or does it signify the horse’s direction of travel, in which case it may commemorate an event such as riding to or from battle?

Producing a drawing of a horse is one thing, but transferring it from paper (or parchment) in enlarged form against the side of an escarpment is quite another. How was this achieved? Was a drawing divided into grids and the grids then laid out on the landscape with ropes or lines, or did someone shout instructions from afar until the depiction of the horse looked right. And how was the whole issue of perspective handled to prevent the horse from looking ludicrously out of proportion when viewed on a slope?

Another question pertains to the animal itself. Why a horse? The name ‘Tysoe’ is generally accepted as being derived from the Germanic warrior god Tyr, although he is not specifically associated with horses. A wolf or a raven might be a more appropriate symbol of battle. There are several white horses etched into the chalk landscape of southern England, so why was the horse symbol so universally significant (See The horse)? If indeed Tysoe’s Red Horse dates back to Germanic times as many believe, why is there no documentary evidence for it? In fact the first record of its existence occurs only in the early 1600s (See The timeline). Before then history is silent, not even William Shakespeare (1564-1616) who may well have travelled the Old Salt Road and whose works are thick with superstitions and tradition alludes to it in any of his plays.

Then there is the problem of exactly how many horses there were. Some say as many as five were etched there over time(See The timeline) (Figure 1). Three of these are thought to lie above Old Lodge Farm, two of which arguably being the main horse and its foal. Two more are recorded much further north on the escarpment adjacent to Sun Rising House which was formerly an Inn, created there by a publican in the early 19th century in order to attract more business. A further suggested location recorded as being to the south is probably a misinterpretation of the landscape but appears on a late 18th century map.

Figure 1. The red spots indicate the interpreted locations of various red horses. North is to the left of the image.

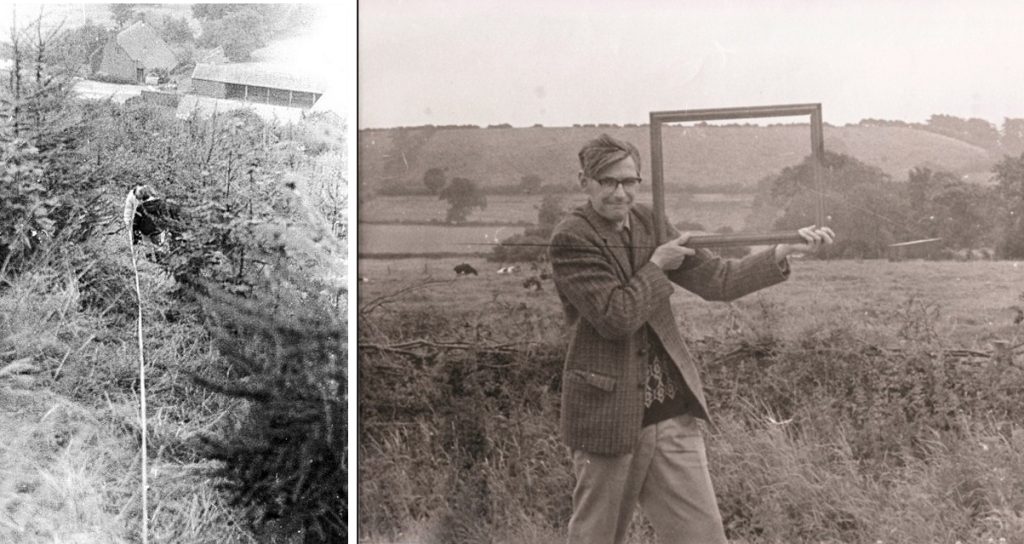

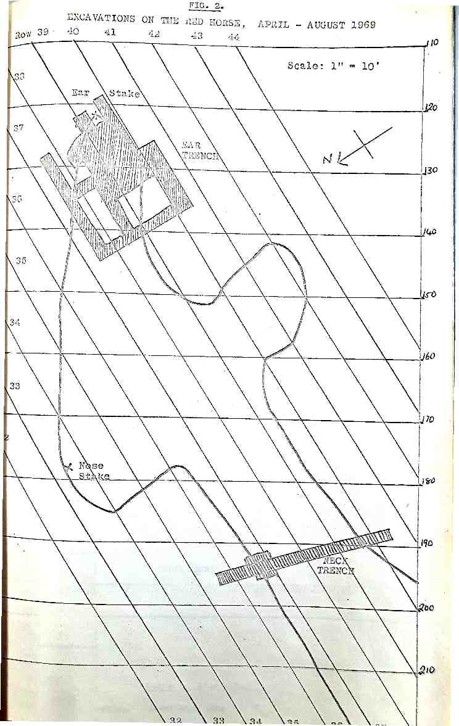

Over the last few centuries the existence and subsequent loss of the Red Horse has stirred the interests of many historians, folklorists and antiquarians, not least being two local men, Kenneth Carrdus and Graham Miller (Figure 2). Kenneth Carrdus was a schoolteacher in Banbury from around 1947 having graduated with a degree in English from Oxford, later serving in the Tank Corps in WW2. He was a keen amateur archaeologist as well as being an accomplished musician and dramatist. Graham Miller was one of his pupils at Banbury Grammar School in the 1950s, later becoming a school teacher himself in Tysoe, living in Saddledon Street. He too was particularly interested in village history and archaeology as well as in being a gifted artist in stone and wood. The two of them spent much of the rest of their lives in investigating the history of the Red Horse and in locating its shape and position through fieldwork, survey and excavation (See The work of Carrdus and Miller) (Figure 3).

In doing so they amassed a huge volume of data and reference material which culminated in the production of a booklet ‘The Red Horse of Tysoe’ initially published in 1965 which was to be edited and updated several times thereafter (See The Red Horse of Tysoe (1965)). To this day it remains one of the few published works devoted to the topic. They recognized that the site had never been investigated previously and were determined to apply whatever new scientific rigour was available. They described earlier studies as being no more than ‘a tissue of chicanery, pseudo archaeology and genuine practical joking, folkloristic fantasy and myth-making mummery . . ‘

Figure 2. Kenneth Carrdus (top) and Graham Miller (bottom right) together with local doctor Sydney Agnew (bottom left) who piloted the plane for aerial photographs.

During their investigations they were aided by two young individuals, Susie Carrdus (Kenneth’s daughter) and Kevin Wyles (one of Graham Miller’s Tysoe pupils who later became recognized as Tysoe’s local historian and who accumulated all manner of general archaeological, artefactual and documentary material relating to the parish). After the deaths of Carrdus and Miller, part of their data collection was archived in Swindon by Historic England, but a large part was also retained by Susie Carrdus who generously allowed THRG access for research and scanning. Together with Kevin Wyles’ material this vast corpus consisted of hundreds of pages of notes, letters, plans, photographs and associated documents which have since been scanned by THRG’s David Low and Carol Clark to preserve them for future investigation. Salient points of their research are drawn out and discussed in some of the sections that follow.

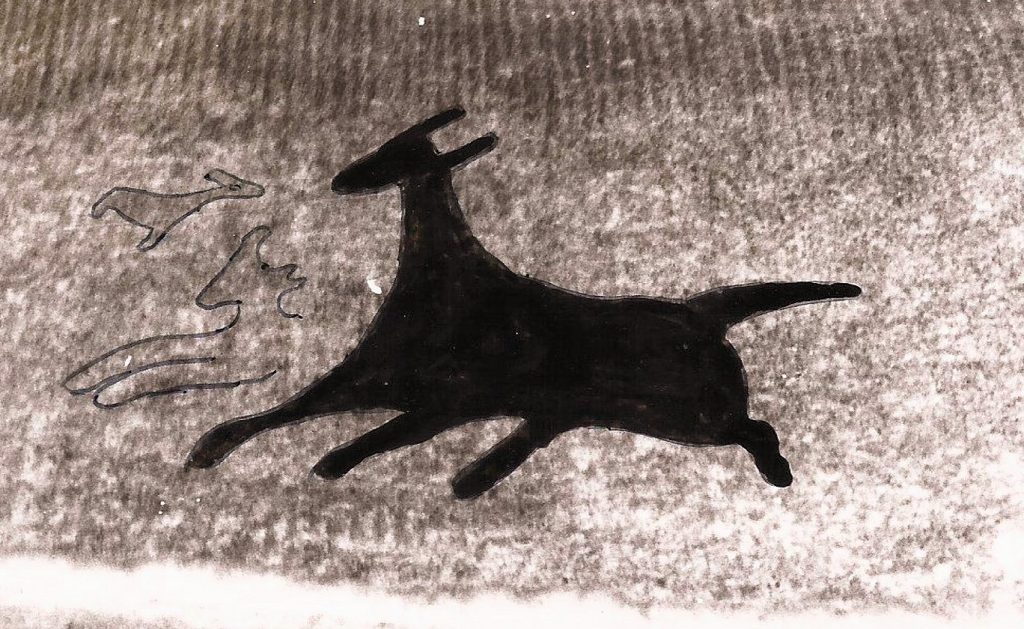

Figure 3. Carrdus and Miller’s interpretation of the Red Horse from fieldwork, survey and excavation

Art in the landscape

The Red Horse is a manmade feature of massive proportion but is hardly alone on the British landscape where monument types range from one extreme at Stonehenge with its ritual or religious significance, to purely functional wind turbines at the other. Some monuments can best be described as rich men’s follies such as Sanderson Miller’s ‘Castle’ at nearby Edgehill (now the Castle Inn), while others take on the role of personal memorials with social or political connotations such as the tall monument to the 19th century Duke of Sutherland. While many of these may have some artistic merit there are others which are intended purely as works of art often with historic or social sentiment. Modern day examples might include Gormley’s gigantic iron Angel of the North at Gateshead alongside the A1, commissioned as a ‘landmark public artwork’ reflecting regional regeneration. Similarly, the Kelpies, two horse heads constructed of steel plates that tower over the road network near Falkirk in Scotland encapsulating the Clydesdale heavy horses that pulled the wagons, ploughed the fields and towed the barges that shaped the geographical layout of the region (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Kelpies

Where does the Red Horse of Tysoe fit among these? This is not the only horse within the context of hill figures in England, albeit being the only red one. The greatest concentration of these horses lies on the chalk downlands of Wiltshire and south Oxfordshire where the removal of turf reveals white underlying chalk. Many of these ‘land carvings’ or ‘geoglyphs’ as they are sometimes known are relatively modern but there is only one that is demonstrably early.

This is the Uffington White Horse located in Oxfordshire on a slope of the North Wessex Downs (Figure 5). The image is spectacular in that it is more symbolic than realistic and is also referenced in land charters from the 12th and 13th centuries. The depiction of the horse is entirely stylistic with thin graceful sinewy limbs and body, quite distinct from the naturally portrayed later chalk horses. The style has parallels on the faces of Iron Age coins minted by the Atrebates in the Thames Valley. Dating to this period is also supported by the use of a technique known as Optical Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) which indicated a date range of between 1380-550 BC from the disturbed buried chalk. OSL is able to identify the time elapsed since a buried mineral was exposed to daylight by measuring the intensity of emitted light which is proportional to the amount of radiation the mineral had absorbed during its buried life. The same technique was used to date the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset (the outline of a male wielding a stick cut into chalk) to around 700-1110 AD and widely believed to reflect paganism.

Figure 5. The Uffington Horse

Exactly what the Uffington Horse represents is open to conjecture. One theory suggests it may relate to sun worship; during the winter the rising sun appears to roll along the back of the horse reflecting the ancient belief that it was horses that dragged the sun across the sky to produce daylight. Another theory suggests that the horse may represent the power of the Atrebates tribe or some form of marker to indicate their territory.

It is only in the 18th century that other horses seem to appear. The fact that many of them are well documented in terms of purpose, method and upkeep has the potential to throw light on the Red Horse itself. The Westbury White Horse is the next oldest after Uffington within the modern boundaries of Wiltshire, having been cut high on a steep slope on Westbury Hill and immediately below the Iron Age Hill Fort of Bratton Camp (Figure 6). It was cut in the mid-18th century on land belonging to the 4th Earl of Abingdon who was notoriously fond of horse racing. The horse was recut in 1778 to commemorate the 40th birthday of George III – the King’s favourite horse was white and his coat of arms included a white horse. In common with many other white horses cut into chalk, its maintenance required continual scouring to prevent it from becoming overgrown.

Figure 6. The Westbury White Horse

The next oldest Wiltshire horse lies at Cherhill, near Calne where it was cut in 1780 by Dr Christopher Alsop who was a friend of George Stubbs the artist famed for his equine paintings. Alsop was also known as ‘the mad doctor’. He delegated the task of cutting the horse to others and supervised the work from a distance using a megaphone. Like the Westbury horse it was cut on the slopes below an Iron Age Hill Fort, in this case Oldbury Castle. It is unlikely that the location of the horses adjacent to Iron Age monuments is of any significance. It is more probable that both horse and Hill Fort required elevated ground to be effective. The example known as the Devizes Old Horse also lies below a hill fort, cut in 1845, but without maintenance it soon eroded and was only faintly visible a century later. It was later replaced by the Devizes New Horse in 1999 which was cut by ‘volunteers’ from a Community Service Group under the auspices of the Probation Service.

The early 19th century saw the cutting of a horse at Osmington in Dorset (Figure 7). This was created around 1808 and is the only figure of a horse bearing a rider, presumed to be George III on his way home from Weymouth. Measuring a massive 85m high and 98m long it became difficult to upkeep to prevent it from becoming overgrown. There was a Local Authority annual budget for its maintenance but this was eventually removed and in 2022 it was reported as looking neglected.

Figure 7. The Osmington White Horse

In 1812, shortly after the cutting of the Osmington Horse another horse was commissioned by landowner Robert Pile at Alton Barnes (Old Pewsey) at the highest point in Wiltshire in 1812. Presumably created for his own glorification it measures some 55m high and 50m long but again proved to be difficult to maintain. This was resolved in 2010 by the Parish Council and current landowner who utilized a helicopter to deliver 150 tons of chalk in order to preserve its shape and colour. Another horse was also cut there in 1937 known as the Pewsey New Horse in order to commemorate the centenary of Queen Victoria’s coronation. Ther following year saw the cutting of the Hackpen White Horse located below the Ridgeway on the Marlborough Downs, presumably to commemorate the same event.

So where, or how, does the Red Horse of Tysoe fit in to this context? As far as dates are concerned the first reliable recorded reference for its existence is in the early 1600s (See The timeline) which makes it the second earliest in the country after the Uffington Horse. The later horses of the 18th and 19th centuries appear either to commemorate particular events or the whims and vanity of their respective landowners and there is no reason to suppose that the Red Horse might be any different. That said, its location on the west-facing escarpment with the sun rising behind could be argued to reflect the mythology of the horse drawing the sun across the sky, perfectly in keeping with pagan traditions and casting a sympathetic glance towards a Germanic origin based on Tyr.

The escarpment through the ages

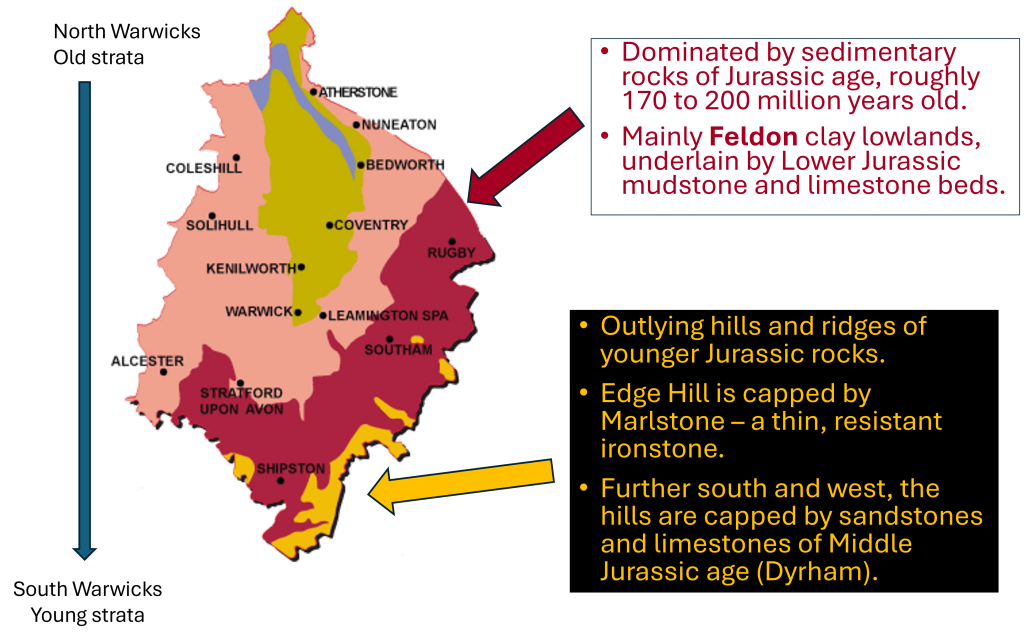

With this position on the escarpment it seems appropriate to consider whether the underlying geology or vegetational history of the area might throw any light on the Red Horses’ position, context or even its date.

From a geological perspective south-east Warwickshire is predominately composed of sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age, roughly 170 – 200 million years old (Figure 8). The Edgehill escarpment consists of younger Jurassic rocks and is capped by marlstone, which is a thin resistant ironstone formed as iron-rich sand in a warm, shallow sea that covered parts of central England roughly 190 million years ago. Known locally as Hornton stone it once provided building material for most of Tysoe’s current houses. The western side of the ridge, now known as the Vale of the Red Horse, is agriculturally rich, benefitting from the Feldon clays underlain by Lower Jurassic mudstone and limestone beds. The Vale also has the advantage of being served by over twenty springs which originate in the upper part of the escarpment and provide one of the key resources necessary for human settlement on the lower slopes.

Figure 8. Geological context of the escarpment (After Geology in Warwickshire www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/article/geology-warwickshire)

At the end of the last ice age, around 10,500 years ago, it is believed that Warwickshire was covered by thick forest, known as the ‘Wildwood’, consisting predominantly of small-leaved lime and oak trees. The first humans to arrive after the end of the last Ice Age would have moved seasonally, living off the land and following the movement of wild animals for hunting.

Evidence for this and subsequent periods of human activity in the area has mostly been found on the east side of the ‘straight mile’ where modern ploughing of arable fields has brought fragments of pottery and artefacts to the surface, allowing small pockets of early activity to be recognised. There are fewer sites identified on the west side of the road for the simple reason that ploughing has been less intensive and much of the land remains in pasture.

Being nomadic, the first humans left little in the way of traces, but over recent years a small number of flints characteristic of this (Mesolithic) period have been recovered from plough soil. During the subsequent Neolithic period (c. 4,000-2,500 BC) the early farmers moved in, began to clear the landscape of trees, and started to cultivate the rich soils on the lower slopes by planting crops such as wheat and barley, raising cattle, sheep and pigs, and building homesteads. A fine polished flint axehead discovered in the Hardwick area, as well as other flints, is testimony to their presence. Evidence for Bronze Age occupation is slight (c. 2,500-800 BC) but nevertheless demonstrates continuity through into the Iron Age and Roman periods where the artefactual evidence, typically pottery, is much more extensive.

It is in the latter half of the first millennium BC and into the Roman period that evidence for Iron Age settlement and occupation is best identified. By the time the Romans arrived in 42 AD, it is likely that more than half of the woodland in Warwickshire had been cleared, the greatest clearance being in the Feldon area. Field walking and geophysical surveys show the area to be rich with Romano-British remains, indicating a vibrant farming community throughout the Roman period of occupation until the beginning of the 5th century AD. The use of geophysical survey techniques in the area east of the ‘straight mile’ has subsequently identified the outlines of buildings, fields and enclosures belonging to the people who lived there and worked the land (Figure 9).

In the early medieval period (c. 410–1100 AD) there is minimal evidence for human activity. This is much the same in the rest of Warwickshire, but land use appears to have continued as before, and was absorbed into Norman overlordship after the Conquest. This saw the beginnings of population increase and the development of the five medieval hamlets (Lower, Middle and Upper Tysoe, Hardwick and Westcote), all served by springs from the escarpment. By the end of the 13th century a person standing on the top of the escarpment could look westwards and see a landscape almost entirely covered in ridge and furrow cultivation divided up into large open units. Aerial photographs taken in the 1960s illustrate the enduring extent of this and, interestingly, show that the upper parts of the escarpment remained uncultivated and were probably used for grazing animals.

Figure 9. Geophysical survey of the area between the A422 (top right) and the straight mile (top left) showing density of probable structures, enclosures and ditches (courtesy of David Sabine)

By the end of the 14th century the Black Death, together with various economic factors, had decimated the population, the hamlets of Hardwick and Westcote had vanished, and much of the ridge and furrow became pasture. From the middle of the 18th century other changes also began to make their mark as new farming systems were introduced across the county. These included rotation of turnips and clover, a general intensification of agricultural production, and a thrust for higher yields.

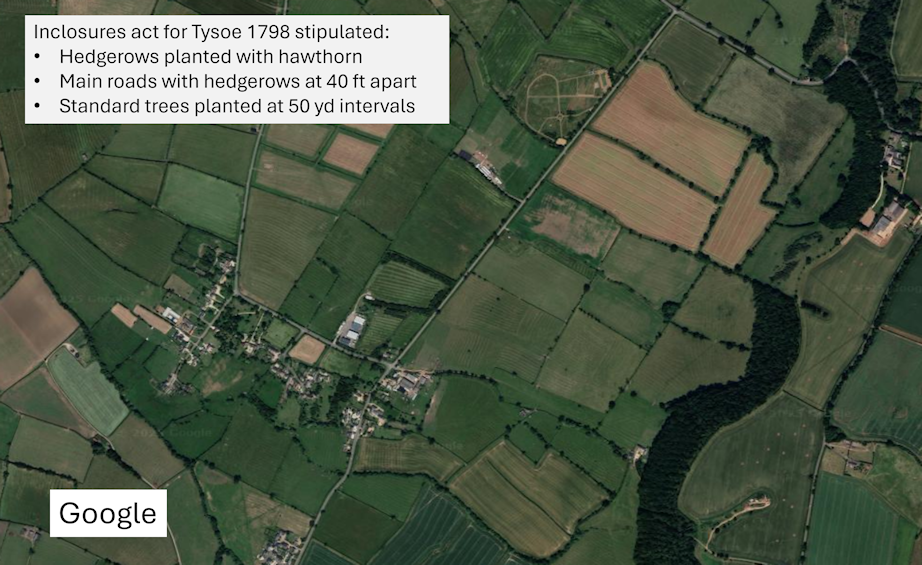

This evolving landscape was to suffer its most significant visual change under the Inclosure Act of 1796 which awarded plots and required the planting of hedges to divide up the earlier open field system (Figure 10). In Tysoe this was implemented from 1798 and specified the planting of hawthorn hedgerows to define fields of various sizes, the planting of trees, and the hedging of roadways. On the contemporary maps showing these inclosures the slope where the Red Horse was cut is recorded as being allotted to one Anthony Lampett and lies just below the higher slope designated as an ‘an ancient inclosure’.

Figure 10. Inclosed fields around Lower Tysoe. The Red Horse lies in the current wooded area to the east of the hamlet

In the parish of Tysoe, most of these hedgerows still survive, but elsewhere many were lost during the changes that characterised agricultural practice in the 20th century. It is estimated that between the 1940s and the 1990s approximately half the hedgerows were lost, mostly due to agricultural intensification and the need for larger fields. It was also a period that saw improved breeding of crops and livestock, the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, not to mention the development of larger and more efficient agricultural machinery.

The escarpment probably remained as pasture from neolithic times onwards until 1959, when most of the upper parts of the escarpment were planted with trees (Figure 11). This included the assumed site of the Red Horse. Sadly, ash-dieback disease has necessitated many trees to be felled recently and for a while, the escarpment will be more open, until the young trees planted as replacements grow.

Today the view west from the escarpment, of fields and hedgerows, is little changed since the inclosures, with the exception of the loss of almost all mature elm trees in the 1970s due to Dutch elm disease. Prior to this, elm was so common in the county that it was called the ‘Warwickshire weed’. What is most striking is that the crops and livestock farmed in the parish have changed little since the first farmers arrived, as long as 6,000 years ago, and cattle, sheep and wheat and barley crops would have been as common a sight as they are today, albeit looking slightly different.

From a land use point of view it has to be said that the Red Horse, being on higher slopes, could have been cut at any time before the mid-twentieth century. Had it been cut, as some believe, in the early post-Roman period it would have witnessed gradual landscape and social change over the centuries. Had it been cut in the early 1600s as firmer evidence suggests, it would still have watched, no doubt curiously, a growing network of inclosures from the late 18th century and the subsequent agricultural improvements of the 20th century. It would also have observed, with detached interest, the Battle of Edgehill slightly to the north. Throughout the centuries it has been a guardian of a rich and prosperous farming valley, a symbol of consistency in an ever-changing landscape.

Figure 11. Comparison of escarpment site of Red Horse between Miller’s 1960s image and current Google earth image

The horse

Placing the Red Horse in the wider context of horse figures on the English landscape (as opposed to other types of animal or bird) is a reminder of the horse’s importance throughout human evolution. The horse has always had an important role to play whether in transport, wars, agriculture, hunting or even racing (the sport of kings). It also has a proud role in mythology, most famously the unicorn, or Sleipnir the eight-legged mount of the Norse god Odin, or Pegasus the winged horse and the Centaur, a half-human, half-horse creature, both from Greek mythology.

Its evolution can be traced to ancestors (Equus) 4 million years ago in the Americas before spreading across to Asia, Europe and Africa by 2.5 million years ago where the horse first encountered early hominids. Far from being domesticated, horses appear to have been hunted and used as a food source. Excavations at Boxgrove in West Sussex have uncovered 500,000 year-old horse bones showing butchering marks indicative of consumption by early humans (Homo heidelbergensis). It was not until the late 4th millennium BC that domestication took place. This appears to have spread from the central steppes of Asia when initially horses were known to have been used for milking before their value in transport became recognized.

Horse riding appeared relatively late in the relationship between man and animal. It was not until the early 1st millennium BC when saddles and bridles were sufficiently developed to allow riding to become viable. It was to have a significant effect on the skeletal structure of both animal and man. For the former it provided an evolutionary change in the vertebral structure to enable weight to be carried, and for the latter extensive riding often entailed skeletal trauma in the hip and pelvic area resulting in a characteristic gait when walking out of the saddle,

Developments in other aspects of horse tack such as stirrups and harnesses provided further innovation. The former enabled the rider to stand whilst riding hence enabling versatile skills in mounted warfare, and the latter underpinned the effectiveness of pulling wheeled vehicles such as chariots in battle, or carts in agriculture. The earliest recorded Roman horses were relatively small compared with modern 21st century horses, probably about the size of Dartmoor ponies, the largest being about 12 hands high to the withers (c. 1.1m). Four of these harnessed abreast would conveniently fit within the starting gates of a chariot race in the reconstructed Roman circus at Colchester. The average height of horses through the Middle Ages as seen from excavations was probably little more, but height began to increase in the post-medieval period (ie after about 1500 AD) to around 13 hands high. The medieval ‘Great Horse’, bred and trained specifically for battle and jousting was rarely more than 14 hands, the size of a modern ‘pony’. A modern ‘hunter’ averages around 16 hands, while heavy horses, like Shires, bred for traction in the 19th and early 20th centuries, can be 18 hands.

There is no doubt that the horse became a symbol of prestige from earliest times. In Romano-Celtic mythology the goddess Epona had a wide portfolio which covered not only being leader of souls into the afterlife and goddess of fertility, but also being protector of equines and patron of cavalry. This says much for the importance of the horse in warfare, also reflected in the depictions of horses on 1st century BC coins of the pre-Roman tribes of southern and midland Britain (Figure 12). Iron age chariots which allowed a warrior to be taken rapidly into battle by a driver and then out to safety again are depicted on Roman coinage. In later Roman times the horse-drawn chariot had become outdated thanks to the development of the frame saddle which increased the ability of Roman cavalry. It allowed the rider to be even more versatile while fighting from horseback, and evidence for a gyrus – a circular arena for the training of cavalry horses – has been identified in the 1st century AD Roman fortress at the Lunt, Baginton. By the end of the Roman period the horse had already consolidated a long history of importance in warfare, as well as in status and ritual.

Figure 12. Celtic tribal horse totems

This continued into the Anglo-Saxon period. Horse trappings were found in the royal graves at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, one of the helmets there also depicting men carrying spears and shields riding into battle. There was also an underlying mythological significance attached to the horse that ran through all early Germanic cultures: it was the horse that transported the dead to the afterlife and was the contact with the supernatural world; it was Odin’s eight-legged horse that was believed to have the abilities of a shaman, and it was the two Norse horses Avakr and Alsvithr which pulled the sun and moon across the sky. Again, is it too far-fetched again to think that there may be some connection between the last of these, the Red Horse and the sun rising behind it in the east?

The Angle-Saxon poem Beowulf which reflects this Germanic warrior-based society is rich with descriptions:

‘Then the lord of warriors commanded eight horses, golden-cheeked, to be led to the floor, inside within the precincts. On one of them stood a saddle decorated with artistries, made worthy with treasure; that had been the battle seat of the high king when the son of Healfdene would engage in the play of swords.’

In later Saxon times horses were often given as prestige gifts together with estates, swords and jewellery. They were seen as such an important asset that the 10th century King Athelstan banned the export of English horses and established a royal stud.

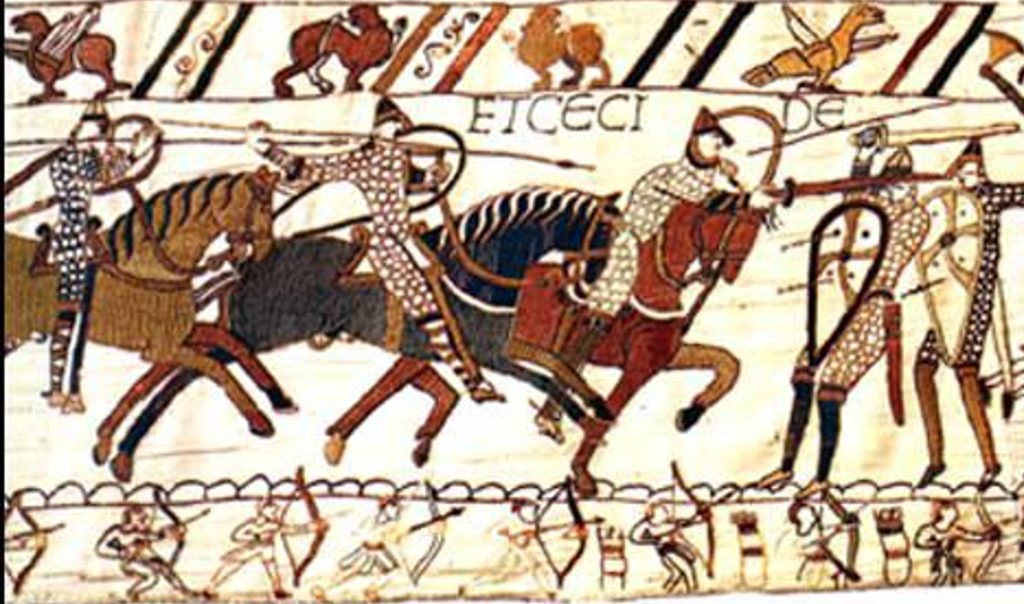

Figure 13. Section of the Bayeux Tapestry showing 11th century Norman cavalry

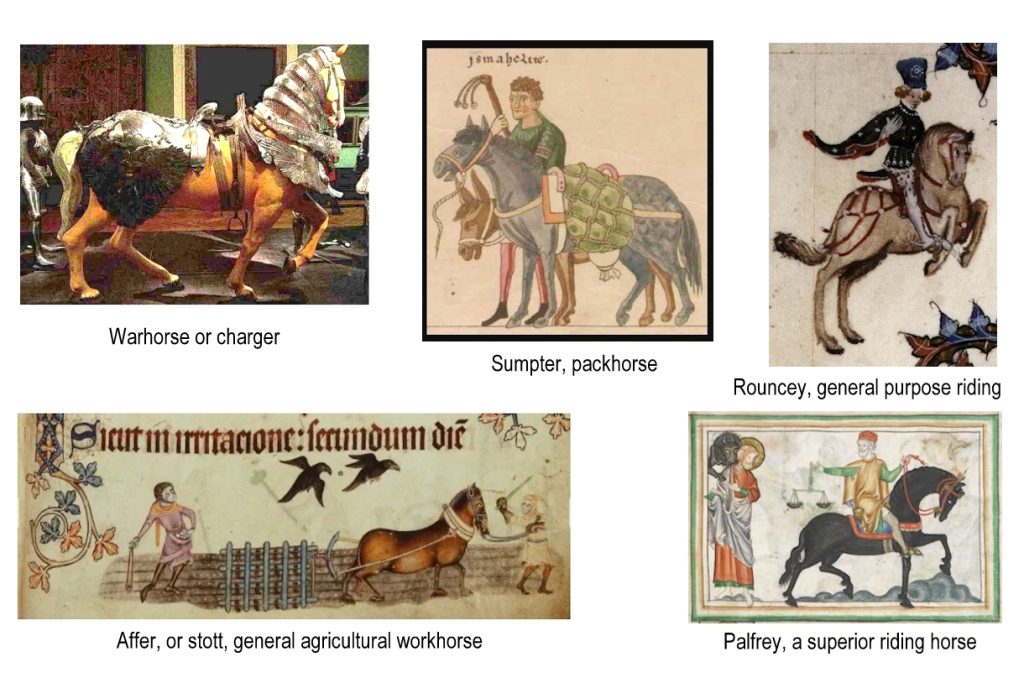

Later, the Bayeux Tapestry illustrates Norman cavalrymen charging with their spears while standing in their stirrups, an improvement adopted in Europe from the steppes in the late Saxon period (Figure 13). Other sources and illustrations show the developing role of the horse in other areas. These include general agricultural work taking over gradually from the ox in ploughing and carting, in recreational riding for the well-to-do, or as a mode of personal transport for those who could afford it. By the time of the Middle Ages the different types of horse were considerable, ranging at one extreme from the small packhorse that carried goods across the rural landscape to the (relatively) large medieval war horse at the other extreme (Figure 14). The cavalry was invariably considered to be the elite battle troop and this prestige continued into the post-medieval period, for example with Cromwell’s ‘Ironsides’, Napoleon’s white charger ‘Marengo’ and in the Charge of the Light Brigade in Crimea. This status was to continue until mechanization and weaponry made horses redundant, beginning in WW1 when an estimated eight million horses carrying supplies and munitions to the front line and moving equipment were killed in action.

Figure 14. Medieval horse types

Away from the battle front horses were being bred for different reasons, notably for agriculture and were essential elements in the agricultural intensification of post-medieval England. Figures suggest that from the early 13th century until the early 16th century the number of oxen used in agriculture was four times greater than the number of horses. However, by about 1500 the numbers were about equal and by 1600 there were twice as many horses, a trend which continued, and by the early 19th century the number of horses had rocketed at the expense of the oxen whose contribution had been reduced to virtually zero. It was the versatility, power and efficiency of the horse that gave it such dominance whether it was for riding, carting, ploughing or for any other agricultural duties required. Some horses, such as the large modern cart horse, were bred specifically in the 18th and 19th century (Figure 15).

Like the warhorse the agricultural horse eventually gave way to the advances of technology, notably the tractor, and gradually became a thing of the past other than for recreation, ceremonies and racing. But the prestige and charisma afforded by the horse led many cultures to adopt them as totem animals and spiritual icons of which the Red Horse of Tysoe is probably an example.

Figure 15. The modern cart horse resulting from 18th – 19th century breeding

The timeline

There have been numerous references and descriptions of the Red Horse, in fact too many to list in full here, but some of the key milestones deserve to be mentioned. Given the cultural importance of the horse throughout history there is every reason to respect the strong tradition that the Red Horse was created in Saxon times and that it commemorates the Germanic god of war Tyr . He is also widely believed to have given his name to Tysoe, the final –hoh or –hog element of the name indicating a slope or mound. The Domesday book first mentions the name Tihesoche (Tysoe) in 1086 and the form continues variously as Tiesoch, Thiesho or Tisho throughout the 12th century. Unfortunately, in none of these sources is there any mention of a red horse. Some say that the horse was cut in 1461 under the orders of the 16th Earl of Warwick (Richard Neville) after the battle of Towton. He slew his favourite horse to demonstrate to his troops that he would fight with them and not from afar, cutting an image of his horse in its memory. There are no contemporary sources to support this, the first reference being made by a Reverend Wise some 300 years after Towton.

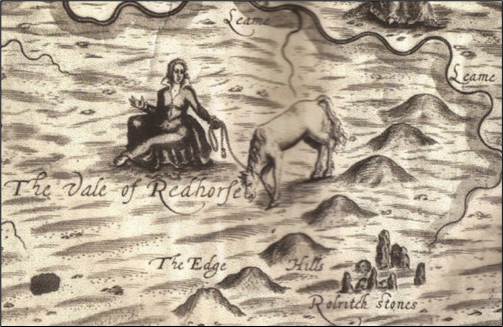

The first recorded mention of a red horse is by cartographer John Speed in 1606 when he denotes an area known as ‘Red Horse Vale’, amplified the following year in Camden’s Britannia which included the passage:

‘Of the redy soil here comes the names of Rodway and Rodley: Yea, and a great part of the very vale is thereupon termed the Vale of Red Horse, of the shape of a horse cut out in a red hill by the country people hard by Pillerton’

In 1612 a topographical poem by Michael Drayton entitled Polyolbion (Figure 16), variously:

‘. . tells Guy of Warwicks famous deeds,

to the vale of Red Horse then proceeds.‘

Figure 16. Illustration from Michael Drayton’s 1612 poem Polyolbion

It might be argued that this relative flurry of Red Horse observations at the beginning of the 17th century might reflect the novelty of a newly cut horse image, but it could equally be the result of one source copying another. However, it was not until 1656 that William Dugdale refers to ‘The Red Horse of Tysoe’ in his Antiquities of Warwickshire, and later still in 1695 when Robert Morden’s map of Warwickshire denotes an area as ‘Vale of the Red Horse’. Around the same time a well-known lady, Celia Fiennes, who famously travelled through England on horseback during the late 1600s commented on the horse, remarking that it was accompanied by a smaller second horse, probably a foal placed adjacent. In 1740 the Reverend Wise who ascribed the Red Horse to the Earl of Warwick post-Towton, also claimed the presence of a third horse. By that time a map of Warwickshire by Henry Beighton produced in the 1720s had depicted a physical horse, not just a name. It gives the impression of being an addition to the map and, interestingly, it shows the horse’s head pointing south not to the north as subsequently interpreted. It seems likely that Beighton had never personally seen the horse. That said, it was clearly a famous landmark which became immortalized in a poem Edgehill by clergyman Richard Jago in 1767 who described it as being in the parish of Tysoe:

‘Carv’d on the yielding turf, amorial sign

Of Hengest, Saxon Chief of Brunswick now

And with the British lion join’d, the bird

Of Rome surpassing. Studious to preserve

The fav’rite form, the trech’rous conquerors

Their vassal tribes compel, with festive rites

Its fading figure yearly to renew

And to the neighbouring vale impart its name’

Clearly Jago was following the tradition that the horse was of Saxon origin. He was born and bred in Warwickshire and was therefore steeped in the traditions of the area. Interestingly he comments on the fact that there was an annual ceremony for scouring the horse in order to retain its integrity; this suggests he was familiar with the locality and its culture.

By the end of the century the Inclosure Act was in the process of being implemented and the landscape took on a new character. Arthur Ashby, son of Tysoe’s Joseph Ashby and later to become a Professor of Agricultural Economics denoted the location of the horse in his plan of the newly divided parish. His plan has a number of flaws and his depiction places it next to the former Sugarswell Lane (now a track) well south of Old Lodge Farm (See Background). No horse has ever been found there and none of the other sources support the position.

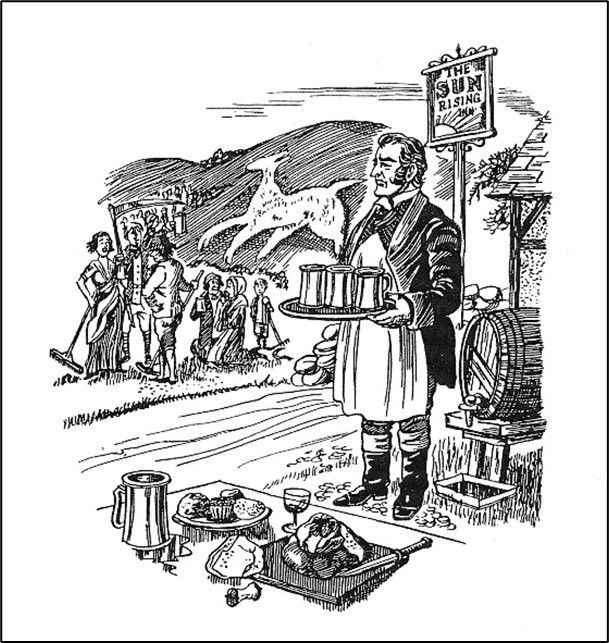

At the turn of the 18th/19th century Sun Rising House was an Inn taking an important position on the toll road (now the A422). The owner at that time, Simon Nicholls, is said to have ploughed up one of the horses despite having profited from visitors helping at the annual scouring and cut a smaller (fourth) horse adjacent to the Inn to help business on a more frequent basis (Figure 17). By 1806 there is a newspaper record of the ‘Saxon Horse and foal’ being grassed over, although by the end of the century Sir Henry Dryden (1787-1837), one of the founders of the Warwickshire Natural History and Archaeological Society, was able to provide the horse’s dimensions, possibly using an earlier source, He also reasserts the red horse as being the creation of the Earl of Warwick in 1461. The horse may no longer have been visible to Dryden but Joseph Ashby (1859-1919) records speaking to people who remember seeing it before 1800. To complicate matters a small fifth horse appears to have been cut near the Sun Rising Inn by its new owner Mr Savoury to revive interest, although this had disappeared by around 1910.

Figure 17. Image of the Sun Rising Inn accompanying narrative by Betty Smith ‘Tales of Old Warwickshire’ 1989

It was not until the 1950s that the whole topic of red horses in Tysoe, none of which was visible, was rekindled. This was due initially to the efforts of Kenneth Carrdus, later in collaboration with Graham Miller, although perhaps a BBC radio discussion on the topic of the Red Horse broadcast in 1953 may have sparked new interest. For the next 20 years Carrdus and Miller researched the long ambiguous history of the Red Horse and initiated detailed survey, photography and archaeological excavation in order to identify its exact position and character – work made more challenging by the planting of trees in the area in 1959 (Figure 18). Their results were initially detailed in their booklet The Red Horse of Tysoe published in 1965 and periodically updated. A review of their efforts shows just how significant their achievements were (See The work of Carrdus and Miller), their work being aired in a TV documentary series Arthur C Clarke’s Mysterious World broadcast in September 1980.

The history of the Red Horse and the apparent mystery that surrounds its origins periodically inspired new comments and ideas, not least being an article in the Banbury Guardian in 2003 which (for no sound reason) claimed the Red Horse to have been created in 500BC and suggested that it should be re-created. This initiated a minor flurry of press headlines such as ‘The Red Horse could Ride again’, or ‘Red Horse or red herring?’ The debate found its way into the Tysoe Parish Plan of 2010 which reflected popular support for two local heritage issues. The first was the popular desire to re-create the Red Horse above Old Lodge Farm, and the second was to replace the sails of the windmill on the hill above Compton Wynyates. Work on the windmill was carried out shortly afterwards, but the land above Old Lodge farm below the Hangings remains untouched to this day.

Figure 18. Left: The difficulty in measuring and surveying through undergrowth and trees on slope.

Right: Graham Miller demonstrating the location of the Red Horse

The work of Carrdus and Miller

Kenneth Carrdus and Graham Miller, together with J. A. Forster who was a teaching colleague of Carrdus at Banbury Grammar School, brought about a new investigation into the Red Horse, one which deliberately over-rode the fringe theories of pagans, aliens, occultists and other ‘dotty interpretations of history’. Previous accounts had led to confusion as to where the Red Horse had been cut, how many different horses had been recorded and the nature of the images on the ground. One of their contemporaries (S. G. Wildman) had interpreted bizarre scenes of animals and humans from cropmarks on the hills above Tysoe.

Their research involved an intensive and meticulous review of documents, maps, early accounts and photographs. Undertaken from the early 1960s it was the first systematic and academically sound attempt to establish the details of the Red Horse itself. There was nothing left to see on the landscape, but local tradition was firm in the belief that the Horse had been located below the Hangings above Old Lodge Farm, an area recently planted with trees. Their research was wide-ranging, initially being a detailed desk-based review of relevant documents which was written up by J. A. Forster, and an analysis of RAF aerial images taken in the 1940s, before commencing work on the escarpment itself in 1964. Armed with the data from this work Carrdus and Miller excavated five small trenches on Old Lodge Hill. These revealed Roman pottery, but no evidence of hill figures.

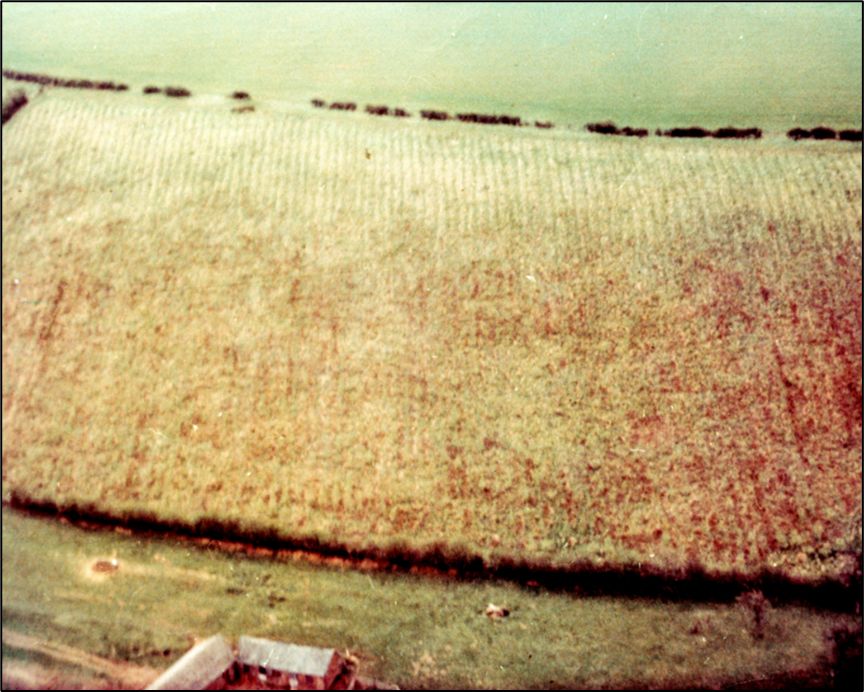

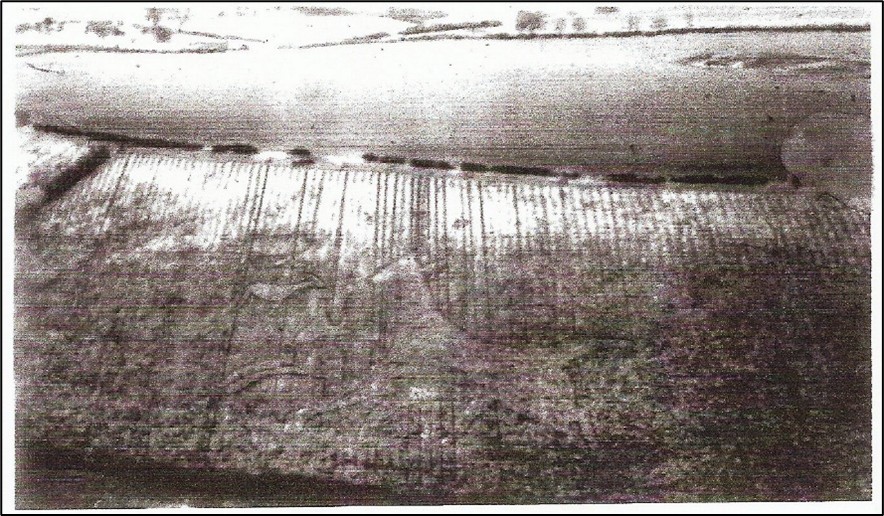

It was only when they implemented a broader set of techniques that signs began to look promising. Observations and photographs taken from the valley indicated a substantial anomaly above Old Lodge Farm which they considered was significant. Aerial photography, including infra-red photography, appeared to show a subtle change in the vegetation (Figure 19). Not only did this occur in the broad area traditionally viewed as being the site of the Red Horse, but it also generally matched the spread of Arrhenartherum elatius (False oat grass) observed and recorded on site visits. A vegetation and soil survey undertaken by Dr Geoffrey Dimbleby from University College, London proved inconclusive but a geophysical survey by specialists from the Radley Institute in 1967 revealed clear evidence of disturbed ground in the area identified from the aerial photographs.

Figure 19. Top: 1965 aerial photograph showing vegetational differences.

Bottom: interpreted outline of horse by Carrdus and Miller

The geophysics technique used was that known as resistivity which involves passing a small electrical current through the ground between two metal probes set about 50cm apart and measuring the resistance to the current between them. Differences in resistance tend to indicate sub-surface disturbance reflected through differences in moisture content (water is a good conductor of electricity). By moving the probes systematically, for example across a grid or along a transect, the method enables differences in the sub-surface to be recorded. Once Carrdus and Miller had identified the rough outline of the horse on the ground they arranged for the Radley Institute survey to be deployed along transects, specifically positioned to include both potential horse and non-horse elements in order to see if there were sub-surface differences. Geophysical survey in the 1960s was far less sophisticated than the automated GPS and digital data-logging methods used today. It was a laborious system which involved writing numbers manually and moving lines and tapes between one transect and the next, problems exacerbated by the presence of young trees, undergrowth, lack of sight lines and a slope of 1 in 4 (25%). As a result, only a very small fraction of the whole animal was surveyed by this method.

Figure 20. Resistivity 1967 survey results (yellow transects) with cropmark plot superimposed

However, despite these logistical issues the differences between horse and non-horse were slight but significant; they could be used to argue for a large area of sub-surface change in the shape of a horse, assuming that the horse outline had been interpreted correctly from the cropmarks. Measurement suggested the animal represented could be roughly 73m from nose to tail and 85m from ear to hoof, its outline being cleverly designed to take perspective into account when viewed from below. The combined data enabled them to plot a broad outline of the horse on the landscape (Figure 20).

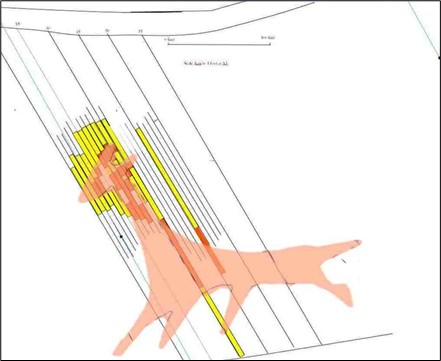

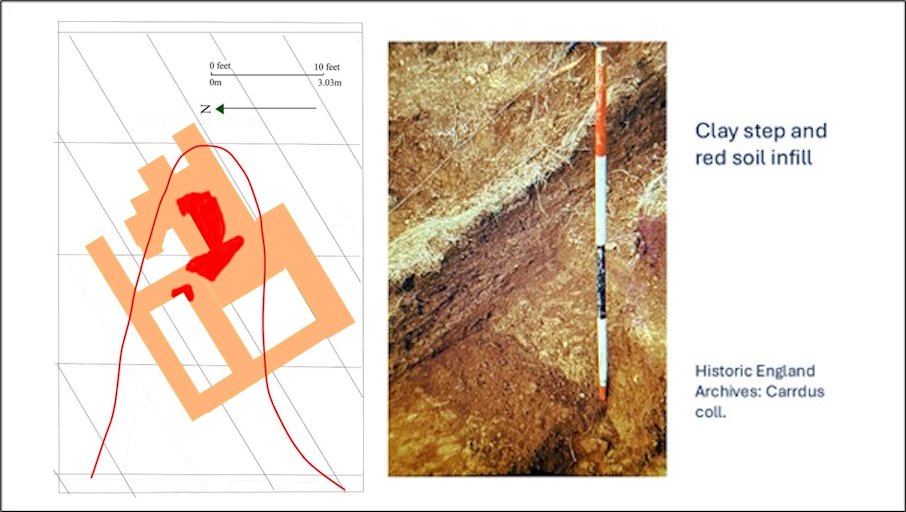

Carrdus and Miller then set about a renewed small scale excavation to identify the nature of sub-surface changes that were causing these geophysical anomalies and vegetation effects. The exact position and size of all their trenches is unclear from their documentation but two were dug across one of the ears and the neck respectively, and a possible third one across a hoof (Figure 21). The results were unexpected and quite remarkable. They discovered that, far from a horse being outlined by a trench, like the Uffington Horse and the Cerne Abbas Giant, the whole beast had been excavated, with a deeper trench around the shape’s edge. Even more significantly for further investigations the shape had not been produced by simply clearing away the turf, it had involved extensive digging to a depth of between 50 and 80cm across the board (Figure 22). The reason for this seems to have been that the geology of the escarpment in that location is predominantly grey-green clay (the Dyrham Formation) with the capping of the red Marlstone Formation (Hornton Stone) lying many metres further up the slope (See The escarpment through the ages). Any horse shaped feature cut to reveal this dull green-grey subsoil would be invisible from any distance. The red soils and rock are certainly present in the excavated trenches but are not in situ geologically. To colour the horse red marlstone rock had been quarried from elsewhere, presumably from higher up the slope where it sat within the natural strata, then transported to the site and used to fill the large horse-shaped excavation.

Figure 21. Plan from notebook showing location of trenches across ear and neck

Figure 22. Excavation of 1969 ‘Ear’ trench showing depth of original workings

This was an astonishing achievement. If the general shape of the horse as defined by Carrdus and Miller is correct (and there is every reason to believe it is) then it would have involved the removal of some 500-800 cubic metres of clay across an estimated area of 80-100 square metres of steeply sloping landscape. In weight terms this was in the order of around 1450-1900 tonnes and no mean achievement. In addition, this spoil had to be carted off site and a similar quantity of red material quarried from higher up the slope before being carted down and spread into the horse-shaped cavity. The management of such an exercise would have been challenging to say the least and the manpower required would have been considerable, not to mention the number of horses and carts working on a slope of 1 in 4. It begs the question as to whether the resources for carrying it out would have been greater than those available in the immediate locality, especially in earlier times. To put it in perspective, the reinstatement of the (much smaller) white horse at Alton Barnes, Wiltshire used a helicopter to transport the 150 tonnes of chalk needed.

Construction of the Red Horse would have required someone with authority to mastermind the project, to have the power and resources to take a workforce away from other duties and possess the stamina to see it through. So much for wealth and power, but if the cutting of the Red Horse was an exercise in self-glorification intended to provide someone’s enduring memory, it failed sadly – we still have no idea who that person was. However, the resources need to create the horse suggest that personal aggrandisement, event commemoration, or individual memorialising may not have been the sole motivation, if at all, but wider issues of community, tradition, and identity may have been in play here. The fact that the Red Horse was designed to be seen from as far afield as Pittern Hill above Kineton, and Pillerton Priors, both 5 miles distant across a wide fertile valley with many settlements between, might suggest that it had a wider significance than might be commanded by a local estate owner. But without a date for its creation much remains speculative.

Where next?

The key questions that emerge from these analyses and observations are simple. When was the Red Horse first created, which person or group of people arranged and organised it, and what was its purpose? Tradition and anecdote perceive it as an ancient creation and well it might be, but not a single record has come to light to support it before 1606. That is a fact, but absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence and the historical record may have been silent for any number of reasons.

In the chronological context of horse figures it sits on its own – probably well after the prehistoric horse at Uffington, but distinctive from the 18th and 19th century animals of the chalk uplands. There must be a specific reason for its creation, not simply one of vogue. Viewed clinically, and unless other evidence is forthcoming, its creation has to be seen as occurring around the turn of the 16th/17th centuries after which it begins to appear on maps, but too early for any association with the Battle of Edgehill in 1642.

Studying the later white horses of southern England provides some clues as to purpose and maintenance: they were the creations of the wealthy for commemoration or vanity purposes and this would chime with the theory that the Red Horse was commanded by the Earl of Warwick to commemorate his horse at Towton in 1461. It is an attractive proposition but fails to address the fact that it took nearly 200 years for its creation to appear in a record or on a map. Moreover, why there? There are other hillsides in Warwickshire, and Tysoe is far from the route between Warwick and Towton in North Yorkshire. More appropriate would have been local dignitaries and land owners, possibly the Earls of Northampton in whose estate the land may have been vested at the time of cutting. Henry Howard the 1st Earl of Northampton (1540-1614) was noted for his interest in culture and charity and enjoyed appropriate wealth, respect and power over a local community. Documentary research needs to be carried out, not just to point the finger at a likely patron, but also a possible notable event worthy of commemoration.

The results of the 1969 excavations by Carrdus and Miller show that there is the potential for undertaking Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating (OSL) of samples from the bottom of the deposits of Marlstone rock in the Red Horse outline trenches. If possible, and successful, such a method may settle the age of the horse and enable some evidence-based theories to be advanced about its origin and the motivation of its creators.

Figure 23. Drawing by Graham Miller

Without the initiative and energies of Kenneth Carrdus and Graham Miller half a century ago, knowledge and understanding of the Red Horse and its history would be much poorer. The horse has been a guardian of the Tysoe landscape for centuries and we owe it to Carrdus and Miller, if not to the Red Horse itself, to add further pieces to the jigsaw. This is not to demystify its enigma but to explore the human forces that underlie its creation.

Edited by John Hunter for THRG, October 2025